On a mission

Beginning in the late 1980s, thousands of Ukrainians and Russians fled their countries in search of a land where they didn’t have to worship in the secrecy of a cellar or in the dark shadows of a forest.

An estimated 27,000 Slavic immigrants have since settled in Spokane, but this people pipeline is now beginning to reverse; increasing numbers are embarking on missions to their homelands in hopes of spreading the same beliefs and prayers they have enjoyed here.

Although many of the immigrants are still struggling to make ends meet, they’ve been able to fund their missions with countless pounds of pocket change and wads of small bills collected in churches and at community fund-raisers. Compared with the hardships of their former lives, the sacrifices being made for the missionary efforts are barely felt, said Ukrainian immigrant Nick Grishko, now a Spokane businessman and pastor at Bethlehem Slavic Church.

“That’s the way we had to live before,” he said. “We have a heart for it.”

There’s a special urgency to return to Russia and Ukraine during these times of massive social upheaval, Grishko said. “There’s a great need over there. We’re trying to help what we can.”

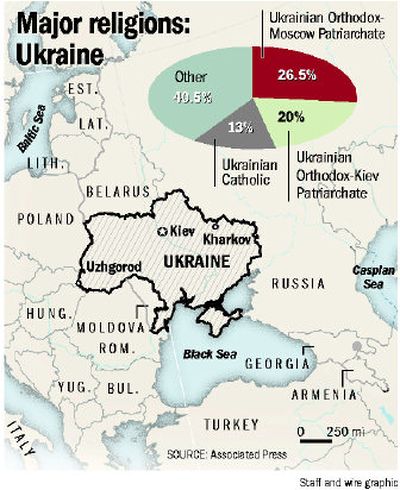

Evangelical churches have long been clamoring for opportunities to make inroads in Russia and Ukraine, where for much of the 20th century worship was a good way to get a one-way ticket to Siberia. That changed with the 1991 implosion of the Soviet Union, but many evangelical missionaries have been met with skepticism and confusion in these countries, which have Christian roots 1,000 years deep.

Still, missionary activity has only increased in recent years, especially in Ukraine following last year’s Orange Revolution, which ushered in political leaders seemingly open to the idea of accepting help from religious-backed groups. One of the revolution leaders and a former prime minister, Yulia Timoshenko, even made the unprecedented statement, “The government must cooperate with Christian organizations to address the social ills of the society.”

Last year, between 30 and 40 missionaries from Spokane traveled to Russia and Ukraine to begin tackling some of these ills, according to estimates from Slavic community leaders. This year, the number is believed to be at least 100, though precise numbers are hard to find because many of the groups are small and informally organized, said Alex Kaprian, pastor at Pilgrim Slavic Baptist Church.

In June, Pilgrim Slavic sent about 35 young people to the far eastern Russian region of Kamchatka to set up Bible camps for children. Mikhail Savin, a leader of the To Russia With Hope group, said he and others plan to return to the region in winter, when frozen rivers will allow them to carry Bibles and humanitarian supplies to some of the region’s most remote villages.

The group raised money for the Kamchatka mission last spring by hosting a traditional Slavic feast prepared by Kazakh native Georgiy Yefremov. During a Sunday church service, as other worshipers listened to a sermon delivered in Russian, Yefremov stood on the sidewalk preparing a post-service fund-raising dinner of plov – a stew of rice, meat, onions, carrots, paprika and cumin – in a giant cauldron over a wood fire. The dish was a favorite of Alexander the Great, Yefremov noted, as he stirred the colorful mixture with a large wooden paddle.

“Any wedding, any celebration, it’s a must-eat dish,” he said. Yefremov’s plov is much sought after by Spokane’s Slavic residents. It’s not an easy recipe, he said. “But I would go to any church to make food to help with the missions.”

A group of teenaged boys – all hopeful missionaries – assisted Yefremov. Looking ahead to the June mission, the young men said they were excited to visit Russia. But tourism would come second to the real purpose, said 16-year-old Anatoliy Borisov.

“We need to bring those kids to God,” he said. “They need help.”

Russia, however, is hardly pagan territory, and the growing influx of evangelical Christian missionaries has prompted anger from the Russian Orthodox Church. The Slavic Christian heritage dates back more than a thousand years, when St. Andrew began preaching the gospel in the hills above Kiev, Ukraine. In 988 A.D., all of Russia was collectively baptized. But the Orthodox church was nearly crushed under 70 years of Soviet rule.

Evangelicals point out that only half or so of Russians and Ukrainians consider themselves Orthodox Christians, leaving ample room for all denominations. Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are now hotbeds of evangelical missionary activity.

Ukrainian radio journalist Art Antonyan of Uzhgorod said he has seen an explosion in the number of missionaries to his city of 120,000 people. Antonyan said many of the foreign missionaries don’t speak the language, but they find ready converts simply by offering food and gifts. The average worker makes about $100 per month in Ukraine, according to 2004 World Bank estimates.

“It’s very easy for the missionaries because there are a lot of poor people, and they don’t know what else to do,” Antonyan said. “When they see foreigners, they are ready to do anything to help their families.”

The missionaries are finding fertile ground, according to Slavic residents of Spokane, because of the vacuum left behind after the Soviet Union crumbled. The promises of capitalism are also proving empty for many. In confusing times, religion is sometimes the only place to find answers, said Russ Rozvodovsky, a Spokane resident and member of Bethlehem Slavic Church.

“People are very thirsty right now, thirsty for God,” he said, moments before church services began on a recent Sunday.