Endangered locations

Dozens of historic sites were damaged or destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. While New Orleans’ French Quarter and Garden District survived relatively unscathed, places like the antebellum historic district of Biloxi, Miss., were ripped apart.

But the dramatic damage is just a fast-forward version of the slower deterioration and destruction affecting hundreds of historic sites across the country and around the world.

Civil War battlefields are being hemmed in by rapid development. A landmark Los Angeles home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright is crumbling under rain-soaked hillsides.

A neglected 18th-century Irish barn and a 2,000-year-old Roman temple flaking apart under the assault of rain and pollution are among the buildings in danger of disappearing forever.

Each year, the nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation releases a list of the 11 most endangered sites in North America. The World Monument Fund does the same for the 100 most fragile spots around the world.

Since 1988, the Washington, D.C.-based group has issued an annual list of the most endangered sites in North America. During that time, 168 buildings and sites have made the roster – including the entire state of Vermont.

This year, the national group is focusing on 11 special buildings or sites. They include Civil War battlefields fighting suburban sprawl, natural treasures endangered by pollution, and the crumbling Cuban home of one of America’s foremost writers.

The current list:

•American historic sites near Washington, D.C.: “The Journey Through Hallowed Ground” corridor, running through Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania, encompasses hundreds of battlefields, historic sites and six homes of former U.S. presidents.

Rapid suburban development from Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia has encroached and in some cases erased important sites from the Revolutionary to Civil War era.

The Journey Through Hallowed Ground is a tri-state initiative seeking public and private efforts to channel growth away from historic areas and recognize what is left of the nation’s 400-year-old heritage in the area.

•Daniel Webster Farm, Franklin, N.H.: The home and family farm of the early American statesman Daniel Webster (1782-1852) was for many years an orphanage that served children who lost parents in the Civil War.

The 140 acres surrounding the house could be carved into subdivisions, even if the historic buildings can be preserved. Opponents want to keep the land designated for agriculture use to preserve the atmosphere as closely as possible to how it looked in Webster’s time.

•Ennis-Brown House, Los Angeles: Architect Frank Lloyd Wright created a handful of textile-block houses in Southern California during the 1920s.

The grandest is the Ennis- Brown House, a hillside home that was damaged by the 1994 Northridge earthquake and heavy rains the past two years. The house has been declared unsafe for visitors. Estimates to repair the house and stabilize the foundation run as high as $5 million.

•Finca Vigia, Ernest Hemingway House, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba: The great American writer lived off and on at Finca Vigia from 1939 to 1960. A lack of maintenance has led to structural instability in the home. The National Trust calls it a “preservation emergency.” The task is made more difficult by the lack of friendly political relations between Cuba and the United States. Cuba has approved permission for work to fix the property, but no significant funds have been allocated to the effort.

•Camp Security, York County, Pa.: The last remaining site of a Revolutionary War prisoner-of-war camp is on land being considered for new housing developments. The camp housed “redcoats” captured in the fight for the nation’s independence.

•National Landscape Conservation System, Western United States: Covering about 26 million acres in 12 Western states, the system includes historic trails, wild rivers, wilderness and dozens of national monuments. Underfunding of enforcement and maintenance by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management has led to vandalism and inappropriate uses.

•Eleutherian College, Madison, Ind.: The first college in Indiana to admit students regardless of their race or gender when it was founded in 1848. The college also served as a stop on the Underground Railroad that helped escaped slaves travel from the South to Canada in the years before the Civil War. The buildings have been damaged by vandalism and lack of maintenance. A National Park Service program has repaired some problems, but there is not enough money to keep up the entire campus.

•Historic Buildings of Downtown Detroit: Downtown Detroit was once one of the nation’s architectural centers. But the “Motor City” has declined in recent decades, and its remaining urban treasures are threatened by neglect and lack of long-range preservation planning.

The National Trust is especially worried about a 100-building “hit list” compiled by the city for demolition. Rather than bulldoze areas for urban renewal, the group wants Detroit’s leaders to work with developers and preservationists to revitalize the city’s core.

•Historic Catholic Churches of Greater Boston: Declining attendance and the need to settle lawsuits over sexual abuse by priests has led the Archdiocese to put several historic churches up for sale, redevelopment and possible demolition.

•Belleview Biltmore Hotel, Belleair, Fla.: The Victorian-era playground for presidents and robber barons faces pressure from developers who would like to convert part of the “White Queen of the Gulf” into residences or tear down the hotel built in 1897 to make room for new homes. Local law offers few protections.

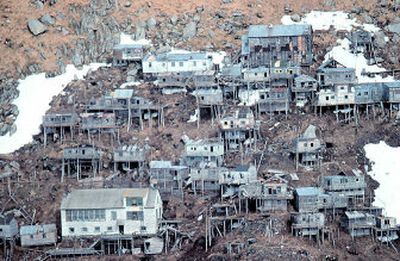

•King Island, Alaska: The Bering Sea threatens to wash away human traces from this island some 95 miles west of Nome. King Island was once home to Inupiat Eskimos, known as “Ugiuvangmiut.” The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs closed the Island’s school in 1959, forcing locals to relocate to Nome. The last surviving descendants of the King Islanders, who return seasonally to live on the island, are seeking help to restore villages damaged by decades of weather.