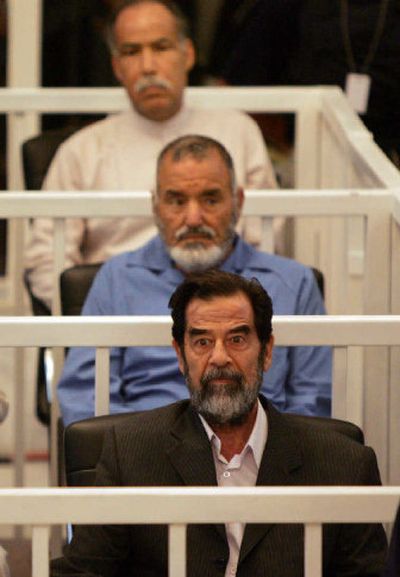

Saddam defiant; trial chaotic

BAGHDAD, Iraq – From the opening minutes of his trial Wednesday, when an unrepentant Saddam Hussein refused to state his name to the judge, it became clear that the process of bringing the former tyrant to justice for the atrocities committed during his regime is going to be long and arduous.

Showing flashes of the defiance that prompted President Bush to wage war against him, Saddam insisted he was still the president of Iraq, jostled with the guards who tried to escort him out of the court and shouted, “It’s a lie!” when the charges against him were read.

After three hours, the court adjourned for six weeks. The only witness didn’t show, one of the defendants forgot who his lawyer was, and technical glitches prevented courtroom observers and millions of Iraqis watching the delayed broadcast on television from hearing much of what was said.

It added up to a chaotic start for the historic first session of what could become a series of trials of the former dictator and his subordinates for the many human rights abuses committed during his rule, for which he faces the death penalty if convicted.

In this case, Saddam is accused along with seven others of involvement in the summary execution of 148 people after a failed 1982 assassination attempt against Saddam in the Shiite village of Dujail, north of Baghdad. The chief judge, Rizgar Amin, listed the charges against the accused as murder, forced expulsion, deprivation of freedom and torture, to which all the defendants, including Saddam, entered pleas of not guilty.

It is one of the lesser allegations against a dictator who is blamed by many of his countrymen for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. Prosecutors say they decided to press ahead with the relatively minor case for the sake of speeding up the process of bringing him to court, 22 months after he was found hiding at a farm outside his hometown of Tikrit.

Appearing older, grayer and thinner than he had at his last court appearance more than a year ago, Saddam shuffled into the court escorted by two armed guards, a pale shadow of the tyrant who ruled his nation with an iron fist for nearly a quarter century.

But when Amin, a Kurd, opened the proceedings by asking the lead defendant to identify himself, Saddam seized the moment. Rising to the microphone with a copy of the Quran in his hand, he greeted the court with a fiery recitation: “Those who fight in God’s cause will be victorious,” he said.

Then, he challenged the judge.

“First of all, who are you, and what are you doing here?” he asked. “Have you ever been a judge before?”

The judge pleaded with the defendant. “Mr. Saddam, we need your full name,” he said. “Please tell me who you are.”

“If you are Iraqi, you know who I am … and you know that I do not tire,” Saddam responded. “I am the president of Iraq, and I refuse to answer these questions because this court is illegitimate.”

After several minutes of sparring, during which Saddam complained that he had been awakened at 2:30 a.m. to attend the session, the judge gave up. Instead, he referred to past documents to identify Saddam, calling him as “the former president of Iraq.”

“I said I am the president of Iraq,” Saddam flashed back. “I didn’t say former.”

It was the first time Iraqis had heard the charges against their former leader and his co-defendants, including his former vice president, Taha Yassin Ramadan, and his half-brother, Barzan al-Tikriti.

The chief prosecutor, Jaafar al-Musawi, the only other court official whose face was shown, described how 148 people from the town of Dujail were rounded up and executed after the failed assassination attempt, “all for the sake of 12 to 15 bullets from a Kalashnikov.”

He said he had documentary evidence that Saddam had directly ordered the crackdown that followed, including the forced expulsion of thousands of local Shiites from their land and the detention of hundreds more. But the witness he had summoned didn’t show up because he was sick, and when he tried to show a video that he said would support his case, the machine didn’t work.

Musawi drew loud objections from the defense team when he launched into a description of other abuses allegedly committed by Saddam, including the declaration of war against Iran, and the judge sustained the objections, ordering the prosecutor to stick to facts of the Dujail case.

Then the defense team complained that the 3,000 pages of evidence they had been given by the prosecution were blank or illegible, apparently because of a photocopying problem, and requested an adjournment.

The judge granted the request, setting the next court date for Nov. 28 and bringing to a close the first brush with justice for the man who stands accused of summarily dispensing it when he was in charge of Iraq.