Bush faces cool reception at summit

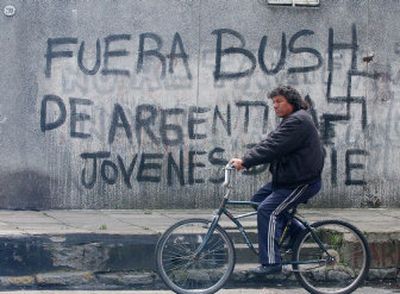

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina – Long gone are the days of heavily armed revolutionaries wandering the jungles of Nicaragua or Bolivia and the cry of “Yankee Go Home!” on the streets of Latin America.

Since the end of the Cold War, military dictatorships have vanished and the region for the most part has embraced capitalism and American-style democracy. But that doesn’t mean it’s entirely at peace with “El Norte,” its powerful northern neighbor.

When President Bush arrives this week at the Argentine seaside resort of Mar del Plata for the fourth Summit of the Americas, leftist activists, students, Indians and trade unionists will gather at a basketball stadium several miles away to protest everything from the war in Iraq to U.S. immigration policy to free trade deals.

“We think his policies are totally contrary to what we want for Latin America and are promoting genocide, domination of workers and their communities and the plundering of natural resources,” said Argentine labor leader Juan Gonzalez, who is heading a protest “People’s Summit” coinciding with Bush’s visit Thursday through Saturday.

It’s nothing Bush hasn’t run into on his travels in Europe. But in play here is a long and complex history, rife with nationalist impulses, in which the United States is viewed as an economic magnet, valued as a donor of aid totaling nearly $1 billion a year, but detested as “imperialist.” The latter sentiment has been exacerbated by the war in Iraq.

Most Latin American governments opposed the war, and only Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic overrode their own protesting publics to send troops or police to Iraq. The 380 Salvadorans are the only ones still there.

Many Latin Americans who once complained that Washington was propping up their dictators now contend it is trying to spread its brand of democracy by force.

But the war on terrorism hits particularly close to home south of the Rio Grande because of tighter border and visa controls. Poor Latin Americans have been waiting for years for a promised guest worker program to get them into the United States, and better-off students increasingly are turning to schools and colleges in Canada, Britain and Australia.

To many Latin Americans, “the war smacks of U.S. imperialism and bullying and is extraordinarily unpopular,” said Riordan Roett, director of the Western Hemisphere program at Johns Hopkins University. “America is seen as an arrogant, run-amok republic that does things without thinking them through.”

When Bush took office, some Latin Americans welcomed the former Texas governor as a politician familiar with the state’s huge immigrant population and problems south of its border. They cheered when he proposed an initiative to ease illegal migration with a guest-worker program.

But the idea dropped off the radar screen after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Bush has started a new push in Congress to get it passed. He has also tried, with little success, to revive President Clinton’s goal of a Free Trade Area of the Americas.

The United States continues pouring aid money into Latin America and the Caribbean. It gave $894 million last year and will spend $983 million this year for programs to fund education, feed children, promote democracy and fight drug trafficking.

A quarter of that money goes toward the drug war, but with mixed results. Some countries say it’s not enough, and many Latin Americans believe the problem wouldn’t exist if America wasn’t a market for drugs.

Bush’s most vocal critic at the summit will likely be Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, a Fidel Castro supporter who accuses the Bush administration of seeking to overthrow him.

But other leaders have plenty of their own issues to gripe about. These include the deportation of immigrants convicted of crimes in America who go home only to commit more crimes, the U.S. trade embargo on Cuba, and Washington’s rejection of the newborn International Criminal Court.