State admits county must make program cuts

For Spokane County officials embroiled in a mental health funding dispute, the issue has come down to a simple fact: The county is receiving less money this year.

In the first three months of the fiscal year, Spokane County received $500,000 less for its public mental health system than it received last year, according to data released by the county Wednesday and verified by the state.

The Department of Social and Health Services, which had previously questioned the county’s projection of a $7.5 million shortfall, acknowledged that deep cuts to social service programs are immediately needed.

“We were struck by the critical need to take some action now,” said Doug Porter, director of the state’s Medicaid programs for DSHS, which sent an audit team to Spokane last week. “We are no longer questioning whether or not they need to be done.”

Spokane County officials plan to cut more than $450,000 a month from services for people with mental illnesses, affecting programs for the elderly, teenagers and children. The cuts come despite the fact the Legislature allocated $80 million this year to support programs previously funded by the federal government.

“We were trying to keep exactly this from happening,” said Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown, D-Spokane, who has worked closely with county officials. “It’s frustrating.”

The budget crisis threatens to unravel the county’s public mental health system, which is operated by the county and United Behavioral Health, a California-based firm paid $1 million a year to oversee the system’s finances.

Earlier this week, Spokane County commissioners raised the option of dissolving the county’s management system, known as the Regional Support Network, and returning mental health operations to the state.

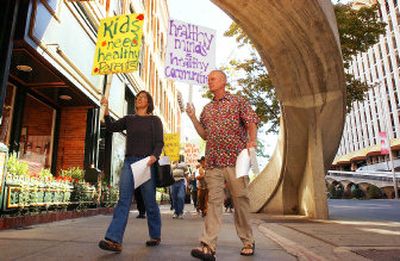

At a rally Wednesday, Cornelius Bakker, the recently retired psychiatric director at Sacred Heart Medical Center, urged the county to remove both the Regional Support Network and United Behavioral Health.

“It was agonizing to sit there and listen to people who had no idea” about patient care, Bakker told a crowd of 50 mental health workers and advocates. United Behavioral Health, he said, “has been of no use whatsoever to any patient in this county.”

A San Francisco-based spokeswoman for the managed-care firm said it was “committed to continuing to work with the county.”

Spokane County Commissioner Mark Richard, who has worked with state officials for weeks to resolve the shortfall, expressed his frustration at the rally.

“If we can’t care for people who can’t care for themselves, then I think government ought to pack it up and go home,” Richard said.

While the state agency acknowledged the county’s shortfall, it also blamed the local officials for some of the financial woes, saying they had exhausted their savings and arguing that broad cuts would have been necessary in Spokane County even if federal funding had not drastically decreased this year.

In a statement released Wednesday afternoon, the agency also questioned the county’s management of mental health services and its monitoring of contractors, but provided few details. The audit is expected to be completed by the end of the month.