Obsessions

At a time when debate rages over whether evolution, creationism or intelligent design should be taught in public schools, “The Exorcism of Emily Rose” takes as its central theme the conflict between religion and science, faith and reason and even good versus evil.

It’s our culture’s obsessions magnified on the big screen, simplified in the one-on-one setting of the courtroom, where there is a winner and a loser.

Scott Derrickson, who directed and co-wrote the movie – which debuted at the top of last weekend’s box office with $30 million – said he did not intend for it to come down on the side of faith or reason.

“I wanted the audience to leave the film with the feeling that they must ask themselves what they believe,” Derrickson said. “Specifically, what do they think about the existence of the spiritual realm? Does the devil exist, and therefore does God exist?”

For some, however, the movie’s position is clear.

“It’s amazing he got away with this,” said Sister Rose Pacatte, director of the Pauline Center for Media Studies in Culver City, Calif., which offers educational workshops on Christianity and the media.

“Even though he plays it close between science and faith, he’s obviously saying, ‘If you don’t believe in the devil, you’re doing so at your own peril.’ “

The movie is based in part on a true story. In the 1970s, a young German girl, Anneliese Michel, died during an exorcism, and the priest who performed it stood trial for her death.

In “The Exorcism of Emily Rose,” a young girl goes to college, where she starts hallucinating and experiencing blackouts and convulsions. Her attacks become more frequent and severe to the point that she is convinced she is possessed by demons.

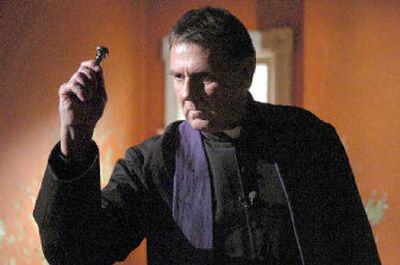

The girl, Emily Rose (played by Jennifer Carpenter), decides to undergo an exorcism by her parish priest (played by Tom Wilkinson). When she dies during the exorcism, the priest is charged with negligent homicide for failing to enlist medical help.

In court, a Methodist prosecutor (played by Campbell Scott) argues that Emily was epileptic and psychotic and needed medical attention. An agnostic defense lawyer (played by Laura Linney) makes the case that Emily was truly possessed.

Things come to a head when the star defense witness takes the stand to explain possession as a real phenomenon.

“Objection!” the prosecutor shouts. “Objection on grounds of silliness.” All this belief in exorcism, demonic possession and the devil is nothing more than “archaic and irrational superstition,” he says.

But for the defense attorney, “This case isn’t about facts. It’s about possibilities. … Facts leave no room for possibilities,” she tells the jury.

Demonic possession is a real possibility in the Roman Catholic Church, which recognizes exorcism as a way to drive out evil spirits through ritual prayer. Pope John Paul II was said to have performed several exorcisms.

Most archdioceses have an exorcist on staff whose identity is typically kept secret, said Tod Tamberg, spokesman for the Los Angeles Archdiocese.

In 1999, the Vatican issued the first updated exorcism ritual since 1614. The revised rite urged exorcists to consult with medical experts before concluding that someone is possessed by demons.

Tamberg pointed out this provision: “The church looks for every last explanation that can be given according to science, psychology and psychiatry before leaping to any kind of conclusion about demonic possession.”

While the movie portrays a tension between religion and science, the Catholic Church always seeks a scientific explanation before deciding on a spiritual one, he said.

“Movies like this are no more a reflection of how true religion works than ‘The Dukes of Hazzard’ movie is a reflection of how real police departments work,” said Tamberg, who said seeing the movie trailer was enough to steer him away from the film.

Derrickson, who called himself “unabashedly Christian,” said he wanted to make a religious film, one that would not only be scary but also “smart, intelligent and meaningful.”

He said he believes in demonic possession, although his co-author, Paul Harris Boardman, does not. Derrickson said he went out of his way to make taking sides in the movie difficult.

“By having an agnostic argue for the spiritual phenomenon and having a Christian argue against it, it leaves the audience in a position where they’re not able to just identify with one polarized view or another,” he said.

Craig Detweiler, chair of the film, television and radio department at Biola University, a Christian school southeast of Los Angeles, called the movie “remarkably timely” for its exploration of evil.

It’s a “post-9/11 film,” he said. “When you have such overtly evil and unjustifiable acts, it causes us to question, what is the eternal nature of the struggle between good and evil and God and the devil?”

For others, the movie’s darkness leaves no room for light.

“I think it’s scaring people into faith,” Sister Pacatte said. “It’s showing that God exists because we can prove the devil exists, and that doesn’t do anything for me spiritually.”

Sister Pacatte had another problem. She couldn’t get any other nuns to go with her to see the movie.

“They don’t like horror,” she said with a chuckle.