Border fence divides opinions

SAN DIEGO – If there’s a war being waged over illegal immigration, then San Diego’s border with Mexico is its most militarized battleground.

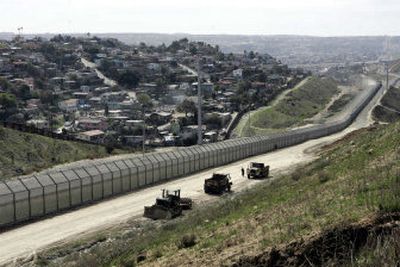

Disputes over the success or failure of the buildup during the past dozen years can be as dramatic as its stature: 14 miles of double or triple fencing, a no-man’s land between countries for U.S. patrols, stadium spotlights and a secret number of sensors and infrared cameras.

For many local residents, the barriers have effectively halted the sensational events of the early 1990s when illegal immigrants ran amok in backyards and on freeways. Crime is down. Illegal crossings have dropped.

On a larger scale, though, the fences have merely moved illegal traffic to more remote areas on the 1,952-mile border, experts say. And smugglers have even constructed elaborate tunnels under the wall to smuggle drugs and possibly migrants.

And the nation’s population of illegal immigrants has grown steadily to record size, nearly 12 million, at a greater pace than before the San Diego improvements, about 700,000 unauthorized migrants a year, according to a Pew Hispanic Center study last year.

At the same time immigrants are dying in record numbers as illegal immigrants and smugglers have moved eastward to more forbidding areas such as the Arizona desert.

Nevertheless, supporters say the San Diego fencing is the end-all paradigm for addressing illegal immigration – tough enforcement on the border – and should be the basis for one proposal to build more fencing for $2.2 billion over 700 miles in five different border zones.

“I would describe San Diego’s border infrastructure as the most efficient (in the nation) and it serves as a model as to what can exist on America’s land border with Mexico,” said Joe Kasper, spokesman for Rep. Duncan Hunter, the 26-year congressman representing a part of San Diego who has been pushing the fence proposal.

Highlighting how San Diego’s fencing lacks concertina wire, Kasper added: “It’s not something you would see in Berlin or Israel. It’s not made of concrete. The point is, it deters illegal entry.”

But critics say it would be America’s Berlin Wall.

Enforcement-only approaches to illegal immigration, like the one passed by the U.S. House, can be deadly and ultimately futile, they say.

Last year, for example, the U.S. Border Patrol recorded 473 deaths, the highest since 1998 and a large increase over the prior year’s 330 deaths – partly because the agency began a new counting method, officials said, noting that the new method included bodies that were recovered by coroners in border areas.

If bodies found on the Mexican side of the border are counted, the figure grows to 516 last year, also a record high since 1995 and greater than the previous year’s 373, according to the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, a group that supports migrant rights. Since 1995, more than 3,500 people have died trying to cross the border, said the foundation’s Claudia Smith. The border patrol says that 2,848 people have died since 1998 and the agency’s search, trauma and rescue teams have rescued some 13,000 people since 1999.

Despite the deadly consequences, stricter enforcement appeals to many constituencies because “it’s a position of being tough on crime,” said Belinda Reyes, an assistant public policy professor at the University of California in Merced and a researcher affiliated with the Public Policy Institute of California.

But the strategy – designed to deter illegal entry – has had another unintended effect: Instead of traveling back to Mexico or another country every 10 months as they did in the late 1980s, illegal immigrants stay longer in the United States, Reyes said.

“It’s way too expensive (to pay a smuggler) and too risky to come across the border, so people say, ‘I’ll stay as possibly long as I can.’ So you have a permanent population or at least a longer-term population,” Reyes said.

Upon first sight, the San Diego fencing seems impenetrable. Steel mats once used for landing strips in Vietnam are used on the Mexican side of the border, traversing hilly terrain and abutting Tijuana’s highways and slums. Then a modern 15-foot mesh fence with an angled overhang lines the U.S. edge.

In between these two main fences is an exclusive road used by Border Patrol with gates bearing militaristic names like “Whisky Two.”

It seems the only way for smugglers and their human or narcotic cargo to thrive is underground. So they do. Last January, “the king of tunnels,” as supervisory agent Edwin Allen of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in San Diego called it, was discovered in a new warehouse in Otay Mesa just outside San Diego.

It was an incongruous picture: A sparkling industrial park worthy of a new suburb was terminus to a half-mile subterranean passage. That tunnel, used to smuggle marijuana and possibly migrants, was noted for its sophisticated electrical, ventilation and water pumping systems. It originated on land belonging to what U.S. officials say is either a communal Mexican farm or the Tijuana airport.

Even in the face of San Diego’s daunting fences, smugglers are “always going to look for the avenue of least resistance,” Allen said.

Not all San Diegans residing on the border agree with the buildup.

At Our Lady of Mount Carmel, which sits atop a knoll with a commanding view of the border a mile away, Father Peter Ruggere, 64, director of the diocese’s missions office, says he and many parishioners oppose the enforcement-intensive proposals. A legalization program for unauthorized workers is needed, Ruggere said.