Impoverished tribe has an edgy idea

HUALAPAI INDIAN RESERVATION, Ariz. — A struggling Indian tribe is hoping to change its fortunes by luring tourists out over the edge of the Grand Canyon on a glass-bottom observation deck 4,000 feet above the Colorado River.

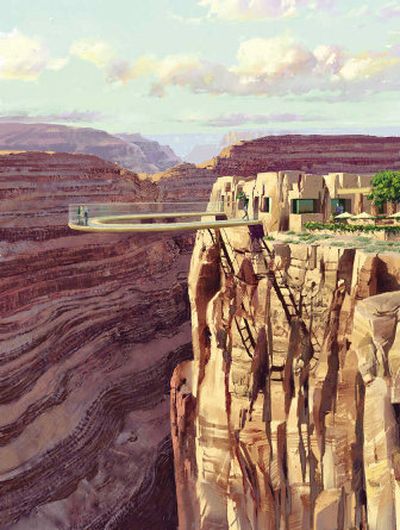

It’s called the Skywalk, a horseshoe-shaped walkway that will jut from the canyon’s lip and offer the kind of straight-down, vertigo-inducing views that had previously been available only to the likes of Wile E. Coyote.

“We have to do something, and this is something spectacular,” said Sheri Yellowhawk, a former tribal councilwoman overseeing the project.

But the $30 million Skywalk, financed by a Las Vegas businessman and set to open in March, has also ignited a debate among Hualapai elders who question whether the prospect of riches is worth disturbing sacred ground.

The Hualapai (pronounced WALL-uh-pie) believe their ancestors emerged from the earth of the Grand Canyon, and the area surrounding the project is scattered with the tribe’s sacred archaeological and burial sites.

“We have disturbed the ground,” said Dolores Honga, a 70-year-old tribal elder who regularly travels to the rim to perform traditional dances. She said workers on the Skywalk site often complain to her about nightmares.

“Our people, they died right along the land there. Their blood, their bones were shattered. They blend into the ground. It’s spiritual ground. This is why you’re awakened,” Honga said.

But other elders say the Hualapai have to do something to end the despair and joblessness that plague the tribe’s 2,200 members, more than a third of whom live below the poverty line.

In 1995, the tribe’s only casino folded after foundering for seven months. Tourists were in no mood to travel 21 miles over an unpaved road to gamble on the reservation — especially not when Las Vegas is just 2 1/2 hours away by car.

Four years later, the tribe invited daredevil Robbie Knievel to jump a side canyon on his motorcycle, hoping the stunt would raise publicity for the reservation as a tourism destination. (He made it across without breaking any bones.)

But years later the tribe’s river rafting and horseback riding operations still draw far fewer visitors than Grand Canyon National Park, about 90 miles to the east.

Planned as an audacious feat of engineering, the Skywalk will be cantilevered 70 feet out past the canyon’s limestone walls. It will be open to the sky, with glass walls and a glass floor.

It will be supported by steel beams anchored 46 feet into the rock on the lip of the canyon. At 4,000 feet above the canyon floor, it will give visitors a vantage point more than twice as high as the world’s tallest buildings. At that height, the Colorado River will be just a thin brown ribbon.

Architect Mark Johnson said the Skywalk will be built to withstand canyon winds of 100 mph and will be capable of holding a few hundred people without bending. It will have shock absorbers to keep it from wobbling up and down like a diving board and making people woozy.

“Hopefully it will give people some security,” Johnson said. “They’ve got a little meat under them.”

Construction began in April 2005.

The Grand Canyon Trust, one of the chief protectors of the canyon, has not raised any environmental or aesthetic objections to the Skywalk, which will be almost invisible from a distance because it will be mostly see-through, and will look puny against the gargantuan canyon walls.

“This is the future of the Hualapai nation,” said Allison Raskansky, a Las Vegas public relations specialist for the project. “This is a view you cannot get at the national park.”