Saddam’s last day

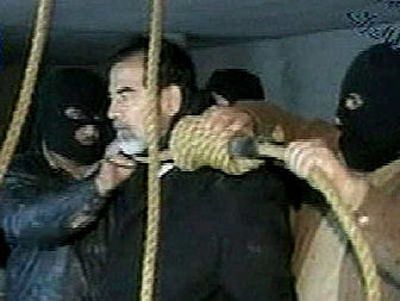

BAGHDAD, Iraq – In the predawn hours Saturday, ousted president of Iraq Saddam Hussein stood calmly at the gallows, a thick yellow noose around his neck, ready to die with an orderliness that now eludes Iraq. Three executioners, men in black masks and leather jackets, stood behind him. Saddam said “Ya Allah,” preparing himself for the platform he stood on to open up.

Suddenly, witnesses recalled, the room erupted in Shiite religious chants, as the Shiite Muslims in the audience seized the moment they have long sought. One man yelled “Muqtada, Muqtada, Muqtada,” unveiling his loyalty to radical anti-American cleric Muqtada al-Sadr.

Saddam smiled, said the witnesses, and said sarcastically, “Muqtada?”

In his final moments, shortly after the dawn call for prayer, Saddam came face to face with today’s Iraq, which he had never met, having spent the past three years in American custody. Since his capture, the Shiites his government violently repressed have come to power. They were the last people Saddam saw before his death. “Go to hell,” a voice yelled in response to Saddam’s remark, according to a grainy video tape taken by a cell phone that was flashed on television networks on Saturday night.

“Long live Muhammad Bakr Sadr,” yelled another voice. Bakr Sadr is the uncle of Muqtada al-Sadr and the founder of the Islamic Dawa Party, of which Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is a senior leader.

Then, Munqith Faroun, who prosecuted Saddam, yelled: “The man is facing execution. Please don’t.” The room quieted down.

According to accounts from five witnesses, as well as Iraqi and U.S. officials, as he neared death, Saddam wore ironed black pants, an ivory white shirt and a black, luxurious top coat. His shoes were polished to a shine. He dyed his hair black and trimmed his silver beard. He waited with dignity.

Saddam began to recite an Islamic prayer.

On Friday night, al-Maliki’s office informed 14 men that they might get a phone call, officials said. Since Tuesday, when Iraq’s highest court upheld Saddam’s death sentence, it was clear that his execution would arrive soon. The al-Maliki government had wanted to execute Saddam early Friday morning, said U.S. and Iraqi officials in interviews. But legal issues, security concerns and Iraq’s political divide postponed the plan.

Shiite leaders, and some moderate Sunni Arabs, wanted to hang Saddam swiftly, fearing any delay could inflame violence and deepen the nation’s sectarian rifts. The Kurds wanted to execute Saddam at the end of the ongoing genocide trial, in which Saddam was charged with orchestrating the killings of tens of thousands of northern Kurds, many with chemical weapons. Other politicians worried about turning Saddam into a martyr if they executed him during the Islamic holidays of Eid al-Adha.

“Up to the last moment, the matter was being debated,” said Mariam Rayis, an al-Maliki adviser.

But by late Friday, Saddam’s execution papers were signed. Muneer Haddad, a judge on Iraq’s appeals court, received the call at 1:30 a.m. A voice said: “Come to the prime minister’s office at 3:30 in order to carry out the execution,” recalled Haddad.

He arrived, along with Faroun, and joined the rest of the group. They included the acting minister of justice, national security officials, members of parliament, and several top al-Maliki advisers. Around 5 a.m. they stepped into two U.S. military helicopters, seven in each. They flew 15 minutes to an Iraqi army base overlooking the Tigris River in Baghdad’s Khadimiya neighborhood, recalled Haddad. It once housed Saddam’s former military intelligence service, where his opponents were executed.

Around the same time, U.S. military officials took Saddam from his prison cell at Camp Cropper, near the Baghdad airport, and flew him to the Green Zone, the enclave that houses the U.S. Embassy and senior Iraqi officials. There, they handed Saddam over to the Iraqis, according to U.S. officials. The Iraqis then drove Saddam in an armored convoy to Khadimiya.

When the helicopters landed, Haddad, Faroun and the acting justice minister were rushed into a small, spare room with a desk, several chairs and a refrigerator. Ten minutes later, Saddam walked in. He wore a wool hat and sat down on a chair before Haddad, who was behind the desk. Saddam’s hands were locked in front of him with plastic handcuffs. “He seemed normal, not confused nor afraid,” recalled Haddad.

Haddad, following Iraqi law, started to read to Saddam the verdict and the ruling by the appeals court. But as he read, Saddam shouted: “We are in heaven, and our enemies are in hell” and “Down with the Persians and the Americans.”

But Haddad kept going. “He tried to raise his voice, but my voice was higher than his,” said Haddad.

At the end of the reading, Saddam’s hangmen arrived.

They took Saddam to a large room with no windows with a staircase that leads to a tall gallows with a large pit at the bottom.

“It was very cold,” recalled Haddad. “It had the stench of death.”

Haddad and Faroun walked with Saddam and his hangmen to the steps of the gallows. Then, one of the masked men, Haddad recalled, turned to Saddam and said: “You have destroyed Iraq, impoverished its people, and made us all like beggars while Iraq is one of the richest countries in the world.”

Saddam replied: “I did not destroy Iraq. I made Iraq into a rich, powerful country.”

Faroun stepped in and ordered the hangman to back away.

Saddam carried a dark green Quran in his clasped hands, witnesses said. At the steps of the gallows, he turned to Faroun and asked him to give the book to the son of his co-defendant Awad Bandar. Bandar, like Saddam, was sentenced to death for the killings of 148 Shiite men and boys in the northern town of Dujail.

“What if I don’t see him?” asked Faroun. “Keep it until you meet with any of my family members,” Faroun recalled Saddam saying.

Saddam took his hat off. The hangmen uncuffed his hands, then placed them behind his back, and recuffed them. They also tied his feet together, said witnesses.

One Iraqi official asked him if he was afraid, recalled Haddad. “I am not afraid. I have chosen this path,” Saddam replied.

Then, the hangmen slowly helped him up the stairs.

The chief hangman offered Saddam a black hood and asked him to place it over his head, but he refused. The man explained that his death would be more painful. Saddam again refused, said witnesses. So the hangman folded the hood and wrapped it around Hussein’s neck like a neck warmer.

“He was shivering and his face was pale,” said one witness who asked not to be identified because he feared for his safety. “I think up to the moment when they put the rope around his neck, he was not believing what was happening.”

Faroun saw a different Saddam. “He was holding tight. He was not scared,” he said.

Saddam stepped onto the platform and, as he recited his Islamic prayer for the second time, the chief hangman asked for silence. Then, the floor of the gallows was opened.

“He died in a tenth of a second,” said Faroun. “He did not move a leg or foot.”

Saddam’s body hung for about five minutes, said witnesses.

Then, it was brought down and covered in a white sheet. A doctor examined him, and then turned around to the audience. “It’s finished,” he said, according to witnesses.

Saddam’s body was loaded into one of the helicopters and flown to the Green Zone, where an ambulance transported his body to an unknown destination.

Saddam’s death was announced on Iraqi television at 10 a.m.