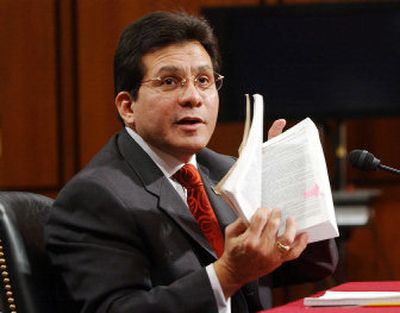

Gonzales defends spying in hearing

WASHINGTON – Facing bipartisan skepticism, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales on Monday defended the Bush administration’s secret eavesdropping program as “vital to the national defense,” but he declined to answer questions about what other anti-terrorism operations the president may have authorized without court approval.

During nearly seven hours of questioning, Democrats and several Republicans criticized the administration’s legal foundation for a spying program that allows intercepting international communications of U.S. residents without warrants.

Senators urged Gonzales and President Bush to seek changes in existing law to accommodate the spying operations, to seek approval of spying cases from a secret federal court that oversees such cases and to explain the program in more detail to members of Congress.

Gonzales argued that the existing law regulating international surveillance “presents challenges” and that Bush derives his authority to order wiretaps without warrants from the powers given a president by the Constitution and from Congress’ resolution in 2001 authorizing the use of force to combat terrorism.

“I don’t think (Congress) can measure the president’s inherent authority … without knowing what you’re doing,” said Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. “Just can’t do it because that authority is not unlimited. It is not a blank check.”

Gonzales’ defense of the operation came on the first day of hearings by the committee into the legality of Bush’s decision to authorize secret electronic surveillance of U.S. residents who are suspected of communicating with terrorism suspects or al-Qaida affiliates overseas.

When Gonzales argued that Bush wasn’t circumventing a 1978 law, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which requires court approval before eavesdropping on U.S. soil, Specter became exasperated.

“That just defies logic and plain English,” he said. At another point, Specter told Gonzales: “The al-Qaida threat is very weighty, but so is the equilibrium of our constitutional system.”

Pressed by other senators on whether Bush is using the same justification to sidestep other laws in the name of combating terrorism, Gonzales replied: “I can’t talk about operations matters that are not before the committee today.”

Democrats and some Republicans persistently questioned Gonzales’ claim that the use-of-force resolution gave the president the broad powers that the administration has claimed since the New York Times revealed the existence of the eavesdropping program in December. They urged Gonzales to seek changes in the law to bring the National Security Agency program in line with congressional desires and to recognize Congress’ constitutional authority as an equal branch of government.

“This statutory force resolution argument that you’re making is very dangerous in terms of its application for the future,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C. “When I voted for it, I never envisioned that I was giving to this president or any other president the ability to go around FISA (the 1978 law) carte blanche.”

Gonzales counseled against changing the law, arguing that doing so could reveal secret details of the operation and further hamstring the president.