Rite of passage

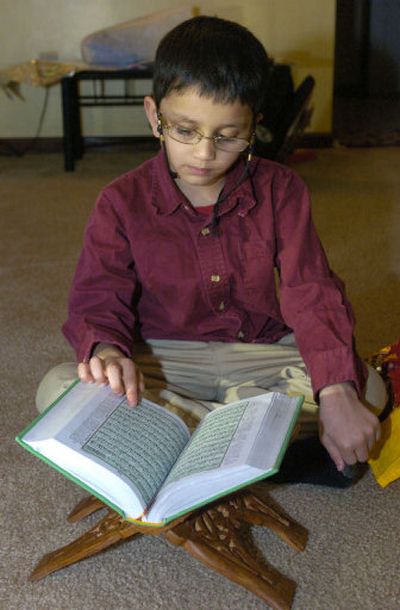

NISKAYUNA, N.Y. – Taha Haq was all of 5 years old when he stood in front of a Muslim congregation and read from the Quran in Arabic.

It wasn’t so hard, he whispers now, curled up between his parents on the living room couch at their home near Albany. After all, he was there to celebrate the fact he’d read the holy book completely.

Now, at age 6, he’s busy memorizing it.

In the world of religion, there are certain milestones. Young Roman Catholics have confirmation and, along with some young Protestants, first Communions.

Now a growing Muslim population in America is importing a rite of passage called Ameen.

The cultural practice is a mostly south, southeast and central Asian one, familiar to perhaps a third of Muslims in the United States.

It has two parts. The first Ameen, or “Amen,” is held when a child finishes reading the Quran, roughly the length of the New Testament, for the first time in Arabic. The child reads the holy book aloud, sounding it out without necessarily understanding the words.

The second, and more rare, Ameen comes when someone finishes memorizing it – a task that can take a full-time student as long as three years.

“It’s like a bar mitzvah for Jewish children,” says Eide Alawam, interfaith outreach coordinator for the Michigan-based Islamic Center of America, the largest mosque in the United States. “It’s an excellent idea.”

America is home to as many as 6 million Muslims, though they remain a small faith group in this country relative to Christians.

U.S.-born blacks and South Asian immigrants each make up about one-third of the community, with the rest from the Mideast, Africa, parts of Europe and elsewhere, according to the Mosque in America study released in 2001 by the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

Muslims in the United States say it’s important to hold on to tradition. Depending on what part of the world they come from, they may celebrate when a child begins reading the Quran, or when a girl decides to start wearing a headscarf or hijab.

“In America, the ceremony is highlighted even more,” says Faizan Haq (no relation to Taha), who teaches Islamic cultural history at the University at Buffalo. “Being here, not in a majority Muslim culture, and still achieving this goal.”

America has many cultural distractions, which is why Muslim parents here have to take a more active role involving their children in the faith, says Fareez Ahmed, a 21-year-old graduate of George Washington University.

Ahmed finished school early to spend his fourth year memorizing the Quran, and now he’s in Bangladesh to perfect his recitation with other students. Islam experts say reciting the Quran from memory in one sitting would take about 15 hours.

In America, Ahmed would memorize the Quran three hours a day and review for another five or six hours.

“I had half-days on Sundays because I couldn’t concentrate when football was on,” he says in an e-mail.

For his Ameen, he hopes to have a backyard party with speakers and a translation in English projected onto screens as he recites a few passages.

“The practice is definitely increasing,” he says. “Especially with the current international situation, it’s really important to know what the Quran really says about certain issues, and having those verses memorized helps a great deal.”

At Taha’s Ameen at the local mosque, he got presents including binoculars and puzzles and was given a feast with friends and family. The meal was topped with traditional sweets, though some American kids now insist on pizza as well.

Faizan Haq says Ameen has not yet bred its own accessories like greeting cards, but he’s noticed a new toy industry catering to Muslim American children. One game has a child press a Quranic verse and provides a translation.

“I bought one for my niece,” he says.

The translation is key. Many Muslims in the United States learn to recite the Quran in Arabic before learning what it means.

Taha’s 5-year-old sister, Iman, is almost halfway through her first reading of the book, and she’s started memorizing it as well. Bolder than Taha, she stands and recites a short passage while holding her mother’s hand. But she can’t explain what she’s saying.

“She doesn’t understand it,” says her father, Abdul Haq, an engineer at General Electric. “We don’t speak Arabic. Just saying the Quran is an act of worship.”