Young man’s selflessness lives on

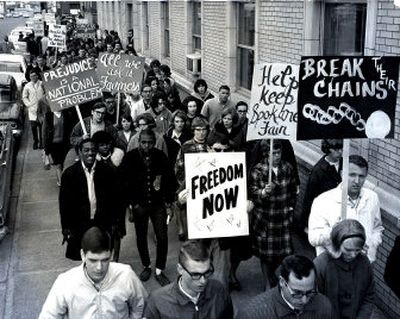

Paul Tusch skipped school that March day in 1965 to participate in a civil rights demonstration near downtown Spokane. The Gonzaga Prep senior must have panicked when he saw the newspaper photographer. Did he raise the “Freedom Now” sign to cover his face in the hope his parents and teachers wouldn’t recognize him in the newspaper?

These are questions no one can answer except Paul. And he died 15 years ago, at 43, in a car accident. This civil rights march photo with Paul in it has a permanent home in our newspaper archives. The photo is a stunner. In 2001, we built a series of stories around it for a black history package.

I interviewed siblings Verda and Sam Minnix for the series; they were black protesters featured prominently in the photo. We wondered about the skinny white kid next to them in the photo, hiding behind sunglasses and a sign.

They say one picture is worth a thousand words. And sometimes, one photo spawns a thousand stories. Here is another one today, about that skinny white kid.

Paul grew up in the St. Augustine neighborhood on Spokane’s South Hill, the oldest of three children. In fourth grade, he met John Lynch and they relished teasing the Irish Catholic girls who sat in front of them in class.

In 1959, John grew ill with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. His doctor ordered bed rest for five months, months which enclosed an entire summer. John was 11. Paul was 12. Paul visited John every day that summer, under pressure from no one.

“He was way serious beyond his years in caring about serious things. If you were his friend, he would die on the sword for you,” remembers Maureen McGuire, Paul’s sister.

John is now 58. He is a Spokane attorney. There is no cure for the arthritis he’s had since childhood, but treatments have improved in recent years, enough to keep John’s inflammation and pain at a manageable level.

In two weeks, John will travel to Washington, D.C., to visit members of Congress about a pending bill – the Arthritis Prevention, Control and Cure Act. Among other things, the bill would encourage more physicians to become pediatric rheumatologists. About 300,000 children have juvenile arthritis. John will go to Capitol Hill on their behalf.

John has never forgotten what it meant to be a child with a chronic, painful condition. In 1959, doctors understood it hardly at all. John was lonely that summer, and he never forgot the visits from Paul, his friend for life. Paul, a kind boy who grew into a kind man, was a loving husband, a father to four daughters, a community volunteer in Mt. Vernon, Wash., where he lived and then died too soon.

A recent UCLA survey of college freshmen nationwide found that the students’ interest in performing community service has surged in recent years. This is no revelation to boomer parents in awe of their teens who build homes for the poor in Mexico or volunteer in shelters closer to home.

What these college freshmen cannot know now is where this doing for others will lead. And where their example will land in the lives of others. Sam and Verda Minnix marched for equal rights in 1965, guaranteeing a better world for their children in 2006. Paul marched alongside them.

And long before that, Paul extended himself for his buddy, John. Now John is extending himself for young people he may never meet whose lives will be better off if the Arthritis Prevention, Control and Cure Act passes.

Paul would have turned 59 Sunday; he was always proud to share Abe Lincoln’s birthday. Paul’s epitaph, fitting and prophetic, reads: “To live in hearts we leave behind is not to die.”