Caution signs

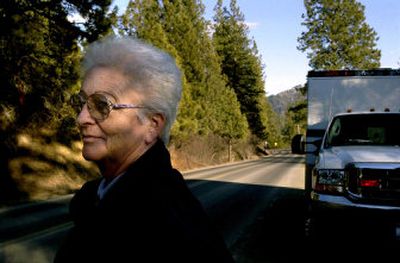

Not many people know state Highway 97 better than Maxine Christensen, who carefully nudged a school bus around its curves and up its hills for nearly three decades. She is intimate with every pothole, every death trap and the stories of the road.

Now Christensen drives an ambulance over the same scenic byway that twists and climbs as it hugs the east edge of Lake Coeur d’Alene. The volunteer job gives her a first-hand look at what can happen if a driver takes her eyes off the narrow road or races around an icy corner.

She responded to two fatal accidents last year and estimates there were about 10 other traffic incidents on the 28-mile stretch between Harrison and Interstate 90. A regional traffic group reports that between 1998 and 2002, there were 72 accidents on or within 500 feet of Highway 97.

“It’s the increase in traffic and people driving it too hard, too darn fast,” said Christensen, who talks about the highway in terms of mile markers, not family homes or bays on the lake. “We’ve got so we drive it once in a while because we want to know what’s going on out there, but we don’t drive it near as much because it’s just got dangerous.”

Like the rest of Kootenai County, the east side of Lake Coeur d’Alene is feeling the pressure of growth.

Homes are filling every vacant nook of waterfront. The opposite side of the road, on the meadows and forested lands that sit on top of the basalt hillsides, is becoming a speculative haven where gated golf communities will fill the former cattle pastures with tees and multimillion-dollar houses.

Traffic is expected to triple; perhaps to what the regional traffic groups say is an unimaginable 8,000 cars per day vying for the few feet of pavement. That’s left the Kootenai County Commission wondering how much longer it can keep approving plans for lake homes and ritzy developments.

The developers of 36-lot Gotham Bay Estates got a lecture last month before the commission approved the homes.

“Eventually we are going to have to draw a line in the sand and say we can’t do this,” said Commissioner Katie Brodie.

Commission Chairman Gus Johnson said it boils down to a public safety issue and that the commission is putting the Idaho Department of Transportation, which oversees and maintains the state highway, on notice that a solution is needed if growth is to continue. Yet the commission stopped short of imposing a moratorium on development.

The state, local highway districts and cities – meeting as the regional traffic group Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization – is conducting a yearlong study of the highway to show what fixes are needed and how much they will cost.

The geography and geology of the area – the very things that landed it the scenic designation – present a challenge for any widening or straightening projects. In many places, the road cuts close to homes or even a few feet from the shoreline. Basalt cliffs rise from the other side.

The study also will encompass Highway 3, which is carrying more traffic through the chain lakes area between Harrison and Rose Lake. Local roads, such as Burma Road, that are overseen by the Eastside Highway District also feel the strain of more cars.

“It’s in the best interest of everyone to take a look at it from a bigger picture and see what is the right mix of improvements,” said Glenn Miles, executive director of the traffic group. The study “provides some certainty for Highway 97 and the capacity.”

The eastside boom has happened within the last three years. The commission and, in one case, the city of Harrison have either approved or are considering more than 1,000 new lots, including two proposed golf course developments. Another golf course community is in the planning stages for about 2,000 acres overlooking Powderhorn Bay, but the Seattle-based developers aren’t ready to say how many homes would be built. These numbers don’t include the smaller developments with fewer than 20 homes that are frequently proposed.

“This is the most active waterfront part of the county,” county Planning Director Rand Wichman said. “More than the west side of Lake Coeur d’Alene or Hayden.”

Some developers are helping pay for the study. Gozzer Ranch, the first golf community on the east side, gave $11,000 and agreed to add two turn lanes on the highway for the Burma Road and Gozzer Road intersections. Miles said the study’s total price tag is unknown until the traffic group determines what the review will include.

“The fact that there is a regional study is good for the whole east side of the lake,” said Andy Holloran of Gozzer Ranch, which will have 375 lots. “There needs to be a review of what’s happening.”

A development company is trying to get county approval for a second gated golf community just down the highway from Gozzer Ranch. Las Vegas-based Kirk-Hughes Development is proposing the 578-acre Chateau de Loire, a French-themed course on the former Flying Arrow Ranch property near Moscow Bay. The development would straddle Highway 97.

In the 1950s, when lake cabins were scarce, Christensen’s father predicted that one day the shoreline would be filled with homes and resorts. She sighed at how his prophecy came true.

When Christensen first started driving the route between Kootenai High School and Echo Bay, her bus would meet a few cars and a couple of log trucks. She kept track of the log haulers with a CB radio so she wouldn’t meet them on a blind curve too narrow to accommodate both a bus and a log truck. Now she won’t even guess how many vehicles she meets when she drives an occasional bus route as a substitute.

Contractors’ pickups, gravel rigs, and semitrucks hauling pipes and other construction goods greet drivers on nearly every corner. That’s not counting the summer traffic or the winter season when folks stop in the middle of the road to gawk at the eagles snatching kokanee from Wolf Lodge Bay.

Christensen once clipped a tripod a man had set up on the centerline of the Beauty Bay curves – likely the most treacherous stretch of the highway because of its snaky and steep grade.

It’s a scary scenario when there’s only a tire-width margin for error. “You see a lot of things out here,” Christensen said. “The road patrols itself, but accidents are increasing.”