Early talent show

It’s so easy to be a codger, sometimes.

You know how it is. You get to be a certain age, and the past is bathed in a certain light – not sepia (we’re not that old), but the glow of an 18-inch Emerson black-and-white.

Life was simpler then. There weren’t 500 channels to choose from; there were four, if you were lucky, and none of them showed “American Idol.” Which made you very lucky, indeed.

Instead, we had “The Original Amateur Hour.” Each week, avuncular Ted Mack would spin the wheel of fortune – “Round and round she goes, and where she stops, nobody knows” – and contestants would show off their talents between the Geritol commercials.

Ah, yes, it was a simpler time. But was it better?

Kultur Video has come forward with an argument in the affirmative. Its two-DVD set (cleverly titled “The Original Amateur Hour”) features clips of famous entertainers who got their starts on the show (and interviews with a few of them, all grown up).

It also offers two complete shows, a couple of theatrical shorts, and earnest narration by singer Pat Boone, a three-time champion on the show in 1953.

In clips from the show’s radio incarnation, we hear Frank Sinatra in his 1935 national broadcast debut, singing “Shine” with the Hoboken Four. We hear a young Maria Callas (performing under the pseudonym Nina Foresti, though some opera buffs have disputed whether it is Callas) in 1935, and an astounding, 10-year-old Beverly Sills four years later.

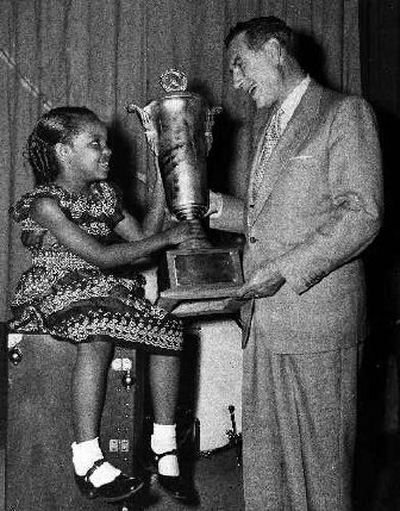

“Amateur Hour” made the transition to television in 1948, joining the Dumont network. Thus we can both hear and see Boone, 7-year-old Gladys Knight, Jerry Vale and Robert Klein, who performs not as a comedian but as a member of a doo-wop group, the Teen Tones.

We also catch a violin solo by 16-year-old Louis Wolcott, who came to be better known as Louis Farrakhan, minister of the Nation of Islam.

Farrakhan, it should be noted, could really play.

In fact, no one who appears on these discs is an embarrassment, and there is no sneering panelist primed to insult contestants who can’t carry a tune.

Which is not to say that “Amateur Hour” never displayed a cruel streak. In the early days, when the show was broadcast locally in New York, its creator and host, Maj. Edward Bowes, would bang a gong to cut off an act that was bombing.

It is said that Bowes dispensed with the gong rather than add to the suffering of the Depression years.

If that’s true, it was an uncommon act of tenderness by Bowes, who earned his stripes as a major in the Army in World War I and never relinquished the rank.

According to American Heritage magazine, desperate out-of-work performers went to New York to audition for the show, and many were housed and fed in city shelters – 1,200 in September 1935 alone. Those who made it on the show got a dinner and $10.

Bowes, meanwhile, pocketed most of the $7,500 a week that came from his sponsor, Chase & Sanborn coffee. He also made a lot of money sending contestants on tour; by 1936, he was said to be grossing $30,000 a week – serious money, then or now, though surely a pittance next to the income of Simon Cowell, whose “American Idol” starts its fifth season in January.

Like “American Idol,” “Amateur Hour” was a phenomenon, among the highest-rated shows on radio and then on television, where it ran until 1970, with a brief and misbegotten revival with Willard Scott in 1992.

Like “Idol,” the public chose the winners, calling operators on duty (MUrray Hill 8-9933) or sending postcards instead of voting with cell phones.

Three-time winners won cash, scholarships or contracts to join the “Amateur Hour” traveling show; similarly, last year’s “Idol” champion, Carrie Underwood, won recording and management contracts, though the sums involved were major multiples of what, say, Pat Boone pocketed.

Unlike “Idol,” “Amateur Hour” was short on glitz. Contestants performed on a simple stage and exchanged scripted pleasantries with Bowes and his successor, Mack.

No fireworks, no bombastic sound or lighting effects.

It is harder to compare the quality of the contestants on the two shows. They both peddle a kind of middlebrow entertainment; if no star of the magnitude of Sinatra or Sills has come out of “American Idol,” well, give Bo Bice some time.

It can be said, though, that it is unlikely that a lot of the acts that appeared on “Amateur Hour” would find a place on “Idol.”

Ted Mack was forever introducing one-man bands, barbershop quartets, impressionists, bottle players, bird callers and disabled entertainers.

Robert Klein always jokes that his doo-wop group was defeated by a one-armed piano player, and he always gets a laugh. But it’s true.

So what’s worse? Glitz and cruelty, or homespun hokum?

It’s so hard to be a codger, sometimes.