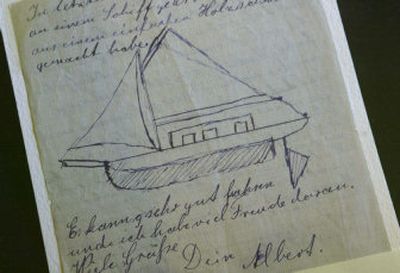

Unsealed letters show Einstein’s personal side

JERUSALEM – A letter from Albert Einstein decrying the attentions of a Berlin socialite is among newly unsealed documents that shed light on the private life of the 20th century’s greatest physicist.

Ethel Michanowski was involved with Einstein in the late 1920s and early 30s, going so far as to chase him to England, said Barbara Wolff of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Albert Einstein Archives, which on Monday unsealed more than 3,500 pages of correspondence written between 1912 and 1955, the year Einstein died at age 76.

Wolff described their relationship as an affair, but disclosed little about Michanowski other than that she was about 15 years younger than Einstein and was friendly with his stepdaughters.

Among the other revelations: Einstein lost much of his Nobel Prize money in the Great Depression, was a more devoted father than previously thought and made no bones about discussing his romantic liaisons with his second wife.

Einstein is known to have had a dozen lovers, two of whom he married, Wolff said.

Most striking about the more than 1,300 newly released letters was the way Einstein discussed his extramarital affairs with his second wife, Elsa, and his stepdaughter, Margot, the archivists said.

Michanowski is mentioned in three of the newly unsealed letters.

In a letter to Margot Einstein in 1931, Einstein complained that “Mrs. M.” – Michanowski – “followed me (to England), and her chasing me is getting out of control.”

Einstein was a founder of the Hebrew University and left it his literary estate and personal papers.

The letters – most of them to Elsa or from his first wife and their two sons – have been in the Einstein Archives for years. But under the terms of stepdaughter Margot’s will, they could not be made public until this July – 20 years after Margot’s death, the university said.

This apparently will be the last time the public will receive such a large number of documents on Einstein, said Professor Hanoch Gutfreund, a former Hebrew University president and physicist.

The new material, available for study at the archive, sheds no light on Einstein’s science or how he reached his tremendous achievements, Gutfreund said. But it illuminates a private side of Einstein, he said.

Einstein’s dalliances and abrupt, even cruel treatment of his first wife, Mileva, have been documented in biographies. He has also been portrayed as an indifferent father unwilling to take on the obligations of parenthood.

Gutfreund said the latest collection shows Einstein to have been more involved with and warmer to his first family than previously thought. Letters from the boys showed “they understood he loved them,” he said.

By filling in some previous gaps in correspondence, the documents “added colors to the image we had of Einstein before,” Wolff said. “Now we have a high-resolution picture.”

The letters also provide the full story of Einstein’s prize money for the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics. Under the terms of his divorce from Mileva, the entire sum was to have been deposited in a Swiss bank account, and Mileva was to draw on the interest for herself and the couple’s two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard.

It has been known for some time that there was a problem with Einstein’s discharge of the agreement, but the details weren’t clear. The new correspondence shows he invested most of it in the U.S., where he settled after being driven out of Nazi Germany, and much of it was lost in the Great Depression.

This caused great friction with Mileva, who felt betrayed because he didn’t deposit the entire sum as agreed, and repeatedly had to ask him for money, Wolff said.

Ultimately, he paid her more money than he received with the prize, she added. The prize was worth about $28,000 in 1921 dollars, a sum that would be worth 10 times that amount today.

The father of the theory of relativity apparently did not want to be bound up with it eternally. In a 1921 letter to Elsa, Einstein confided, “Soon I’ll be fed up with the relativity. Even such a thing fades away when one is too involved with it.”