UI chips prove to be powerful space tools

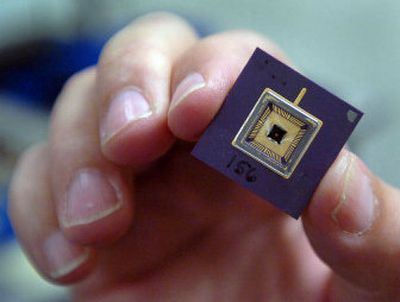

When NASA launched three 55-pound satellites this spring, it sent along three tiny but complex pieces of University of Idaho research.

Three months later, the UI microchips had performed perfectly – doing the same work as an older chip using several times less power. The implications of a low-power processing chip are huge for space exploration, where efficiency is at a premium. But the development also suggests the possibility of more mundane applications like lower-power cell phones or laptops, researchers say.

“Right now this is a very new idea,” said Pen-Shu Yeh, senior engineer and technical officer with NASA. “People haven’t caught up with it yet.”

The chips were the latest project of researcher Gary Maki and his team at the Center for Advanced Microelectronics Biomolecular Research, centered in the UI’s Post Falls research park since 2002. The center’s tiny electronics have been a part of space missions ranging from the Hubble Telescope to the Mars Odyssey.

The latest chip runs mathematical operations that clean up and correct data the satellite is collecting – not unlike clearing out the static in radio reception. The three micro-satellites launched March 22 gathered readings on the Earth’s magnetic field.

“It runs on half a volt, as opposed to five volts or three volts,” Maki said. “That was a major breakthrough for NASA.”

UI designed the chip, which performs millions of calculations per second, based on NASA science, and had it manufactured at a Pocatello firm. The chip worked well in earth-bound experiments, but the real test came when the satellites went up.

“Until it’s in space, you haven’t proven it will do everything you say it will,” said Sterling Whitaker, a research professor and member of the UI team based in Albuquerque, N.M.

NASA crews monitored the satellites constantly. The UI chip ran parallel operations with a high-powered chip and “there was no difference,” Yeh said.

The micro-satellites, known as the ST5, tested a variety of other new technologies, including more efficient solar panels, communications systems, and miniaturized “micro-thrusters.” The 90-day mission is complete, and the satellites will remain in space until they drift back toward the Earth’s atmosphere, where they will burn up.

Information about the new chip will be presented at an upcoming symposium, and scientists will begin exploring whether the chip’s technology can be used in larger operating systems. Yeh said the energy savings could be huge. Roughly half a satellite’s power use is put toward digital operations. If the power requirement could be slashed, satellites could use smaller solar panels or carry less fuel.

It might also be applied in other space exploration, such as building longer-lasting robots to explore the surface of the moon or Mars, Yeh said.

Maki and his crew began working on the chip in 2000, and their research was funded by roughly $5 million in grants from NASA and the Department of Defense. They’re now working on applying the low-voltage approach to a computer that runs overall systems, rather than single functions.

Whitaker said the chip has great potential to further exploration of the solar system.

“I think it will have a really positive impact on the space program,” he said.