Bush betting the house on al-Maliki

WASHINGTON – President Bush flew to Baghdad last week to size up Iraq’s new leader. “I have come not only to thank you,” he told U.S. troops gathered in the Green Zone on Tuesday, “but to look Prime Minister Maliki in the eyes – to determine whether or not he is as dedicated to a free Iraq as you are.”

The presidential determination? “I believe he is,” Bush said.

The snap assessment recalled Bush’s famous assertion that he had sensed Vladimir Putin’s soul and showed how Bush often appears more comfortable with his gut-level assessment of foreign leaders than the one he gets from briefing papers prepared by his intelligence agencies.

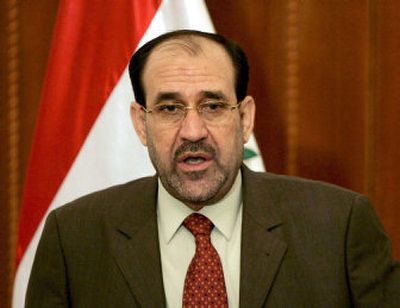

Much is riding on the president’s judgment that Nouri al-Maliki, an untested leader who was little known by most senior U.S. policymakers until only two months ago, is capable of healing the divisions that have torn Iraqi society apart and providing the basic services that have been lacking since the fall of Saddam Hussein.

Nothing less, perhaps, than the success of a presidency that has come to be defined by its enterprise in Iraq. Many U.S. officials and outside experts believe al-Maliki’s new government represents America’s last opportunity to stabilize Iraq after three years and withdraw 130,000 troops without leaving the country in chaos. And while even critics have agreed with the administration’s assessment that the new government is off to an encouraging start, they worry that the cleavages in Iraqi society are beyond al-Maliki’s capacity to bridge.

“The administration has made a major policy decision, to put all its chips on the Maliki government and then double down,” said Richard Holbrooke, the former ambassador and Democratic foreign policy voice. “They are gambling that Maliki can succeed. It’s a lot of baggage to put on the back of this man. But I deeply hope they succeed. Otherwise, it is hard to imagine the consequences.”

Mithal Alousi, a parliament member who heads the secular Iraqi Nation Party, said it is too soon to tell if the Bush administration’s public faith in the new prime minister will be rewarded. “Bush’s visit showed how serious the American government is taking the political process and the Iraqi government,” Alousi said.

But he questioned al-Maliki’s stated intention to curb the power of militias that are a threat to public order. “I am not sure Maliki will do anything, even though he understands what a dangerous situation it is for militias to be in power,” Alousi said. “He needs to understand he is prime minister for all of Iraqis and not just for Shiites. It is not clear he does.”

Since Hussein was toppled in 2003, Bush has been looking unsuccessfully for a partner in Iraq – a version of Afghanistan’s Hamid Karzai. The first appointed prime minister, Ayad Allawi, was a tough-talking former Baathist who lacked a wide political constituency. His successor, Ibrahim al-Jafaari, was elected interim prime minister by Iraqi legislators and hailed from the Islamic Shiite Dawa Party; while he had more popular support than Allawi, his elusive and indecisive manner eventually soured U.S. officials.

Al-Maliki was Al-Jaafari’s top aide, and his selection after elections for a permanent government in December came after months of backroom negotiations and Americans making it clear they would not accept Al-Jaafari as the permanent prime minister. A second-tier figure, he was barely known to senior U.S. officials in Washington, and his background of fierce loyalty to the Shiite cause and ties to Syria – where he spent part of his years in exile – was of concern. Some officials thought he would be more sectarian than he has proved.

Indeed, over the past two months, al-Maliki has impressed Washington, senior administration officials have said. He has established priorities: addressing the spotty electricity service, cracking down on sectarian militias, and trying to reconcile – perhaps through amnesty for those who have not killed Iraqi civilians – with elements of the Sunni insurgency.

The fact that al-Maliki has set priorities represents an improvement over his predecessor, Bush advisers say. They also point to al-Maliki’s practical side: He sought out help from the U.S. government on how to set up his executive office. “He’s a guy who thinks about how I can make this work,” one senior official said.

Bush’s initial public reactions to Allawi and al-Jaafari were also favorable, so in some respects his embrace of al-Maliki was not unexpected. Still, his several hours with al-Maliki in Baghdad seemed to solidify the bond Bush appears to crave with foreign counterparts. Traveling back to Washington on Air Force One, Bush told reporters that al-Maliki impressed him as “a no-nonsense guy that talks about priorities and how he’s going to achieve those priorities. And that’s comforting.”