Afghan Christian unlikely to face trial

WASHINGTON – The case of an Afghan man who could be prosecuted and even put to death for converting to Christianity has unleashed a blizzard of condemnation from the West this week and exposed a conflict in values between Afghanistan, a conservative Muslim country, and the countries that have helped defend and rebuild it in the four years since the fall of the Taliban.

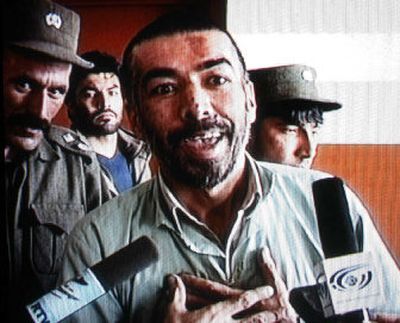

The case of Abdul Rahman, a longtime Christian convert who lived in Germany for years and was arrested last month in Kabul, has also highlighted the volatile debate within Afghanistan over the proper role of Islam in Afghan law and public policy as the country struggles to develop a democracy.

Diplomats from several countries said Wednesday that Rahman, 41, now seems unlikely to be tried or executed. Prosecutors in Kabul said he might be mentally unfit to stand trial, a sign that the government may be seeking to avoid confronting its Western allies without giving ground on Islamic law, under which conversion to another religion is punishable by death.

But the case, the first of its kind since the Islamic Taliban movement was toppled in 2001 by a U.S.-led military invasion, continued to draw protests from the governments of Italy, Germany, Canada and other NATO nations, at a time when NATO forces are beginning to replace tens of thousands of U.S. troops as the principal defenders of Afghanistan against Taliban and al-Qaida insurgents.

It also put pressure on President Bush, who visited Kabul last month to show support for Afghan President Hamid Karzai. A number of U.S. Christian and conservative groups demanded this week that Bush take action, and one organization accused him Wednesday of propping up an Islamic fundamentalist regime in Kabul.

“This is an extremely sensitive issue here and an extremely serious issue back home,” Abdullah Abdullah, Afghanistan’s foreign minister, said Wednesday. “Every time we have a case, it is like an alarm. These contradictions will not go away with one or two cases.”

Bush, on a visit to Wheeling, W.Va., said Wednesday he was “deeply troubled” to learn of Rahman’s possible prosecution. “That’s not the universal application of the values that I talked about” when speaking in Kabul, he said. He stopped short of calling for the case against Rahman to be dropped but said he would work with Karzai’s government “to make sure that people are protected in their capacity to worship.”

Bush’s comments were tougher than those made earlier by administration officials. On Tuesday, a State Department spokesman urged the Afghan government to “conduct any legal proceedings in a transparent and fair manner.” R. Nicholas Burns, the undersecretary of state for political affairs, said that the Afghan constitution “affords freedom of religion to all Afghans” and that the U.S. government hoped for a “satisfactory result” of the case.

The initial low-key response apparently infuriated Christian conservative groups. Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, complained in a letter to Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice: “How can we congratulate ourselves for liberating Afghanistan from the rule of jihadists only to be ruled by radical Islamists who kill Christians? … Americans will not give their blood and treasure to prop up new Islamic fundamentalist regimes.”

Although Rahman is the first Afghani charged with converting since the fall of the Taliban, Afghan courts have recently prosecuted or harshly criticized individuals for other alleged anti-Islamic acts, including a presidential candidate in 2004 who questioned the right of Muslim men to have multiple wives and a magazine editor last year who challenged the doctrine that conversion from Islam is a capital offense.