The Home Planet: Songbirds remind us of simple truths

I got caught speeding last week.

Not by the police, but by a bird. A robin.

As I drove through my neighborhood, distracted and busy, already late and in a hurry to get where I was going, the robin – punch-drunk with spring fever – dove suddenly out of one of the tall pine trees and swooped toward my car. We almost collided.

Only a quick and minute adjustment by each of us saved him. He turned and swept up over the hood of my car. I swerved and slowed.

The bird flew away and I kept driving.

But I confessed to an old sin.

Zipping down another street, in another place, I saw a flash of movement out of the corner of my eye. Then I heard something strike the car.

I stopped and found a mockingbird lying some distance away, where he had tumbled after the impact.

His feathers were ruffled and torn, and one wing jutted at an odd angle. The injured bird made only small, reflexive movements and a faint chirping sound. It was obvious he was broken and dying.

I felt awful. Like a murderer. Shaken by my part in the whole thing, I couldn’t bring myself to drive away and abandon the poor creature to suffer there alone. So I sat down on the grass beside him.

You don’t usually see mockingbirds here in the Northwest, but they flourish on the West Coast, through the Midwest, the South, and up the East Coast.

Mockingbirds are plain gray, with a stripe of white on their wings, but what they lack in color, they make up for in song.

If you’ve never heard a mockingbird, you’ve missed something loud and wonderful. They sing all day and all night if they’re in the mood. They mimic other birds and other sounds.

Mockingbirds are fearless and cocky, and they don’t seem to mind people. They bully the neighborhood cats, swooping low, often grabbing tufts of fur as they go, and then retreat back to the trees to sing some more.

That day, as I sat keeping vigil over a fragile bird that had been no match for my car, feeling guilty and miserable, I thought about Scout.

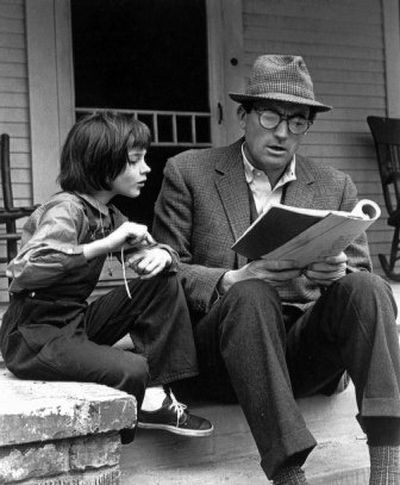

In Harper Lee’s Pulitzer prize-winning novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Atticus Finch, the wise, soft-spoken and respected small-town attorney, gives his children air rifles. Then he tells son Jem and daughter Scout that it is a sin to kill a mockingbird. Finch had been told this by his own father after he was given a gun and warned not to turn it on the birds.

Scout had never before heard her father talk like that. She asked their neighbor, an old friend of the family, what he meant.

“Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us,” Miss Maudie explained. “That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

I stayed with my mockingbird until he died. And I felt as guilty of that death as if I had pointed a gun at him and pulled the trigger.

I need to remember that in some ways it’s as much a sin to hurry through life, barreling from one task to another, speeding across the days and weeks and months with minds that are full of too many details and not enough music, as it is to shoot a songbird.

I know this because alittle bird told me so.