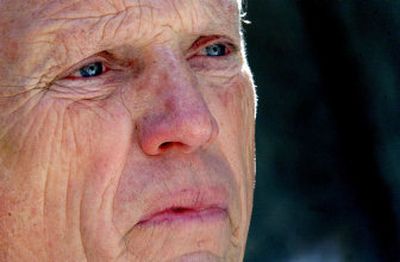

‘It affects you. My wife, it affects her a lot’

It’s May again and the grass has grown high along Bob Hollingsworth’s driveway.

A year ago – last Mother’s Day weekend – the 73-year-old real estate broker hired a neighbor kid to mow the green strip leading to his Wolf Lodge home.

Slade Groene did a good job, too, as Hollingsworth meant to say when he dropped off the $12 he owed the Coeur d’Alene middle-schooler on May 15.

But as people across North Idaho – and the nation – know too well, Slade never got his money.

When Hollingsworth stopped at the white cinderblock house on Frontage Road that evening, he became the first witness to a crime that has reverberated not only far and wide, but deep in the communities of the Inland Northwest.

At the time, Hollingsworth had no idea that accused killer Joseph Edward Duncan III had embarked on a spree that left three neighbors dead and two children missing. A year later, however, images of the discovery at the house down the road still linger.

“I went to the door and saw that door and that porch,” Hollingsworth recalled. “I butcher lambs and I know what real blood looks like. I knew somebody had been murdered here.”

Hollingsworth’s call to the Kootenai County Sheriff’s Department launched a criminal investigation expected to culminate in an October trial. But the grisly incident also sparked emotional and social reactions that rippled across the region, touching those directly involved and those connected by virtue of shared community.

“You wouldn’t be human if it didn’t impact you in some way,” Sheriff’s Capt. Ben Wolfinger said. “Everybody who had a part in it was impacted in some way, shape or form.”

A crime of such magnitude, stretching on for months as it did, transcends individual loss, a regional trauma expert said.

“That’s especially true in a rural or frontier community where everybody knows everybody – or at least knows their best friend,” said Ann Kirkwood, a senior research associate with the Idaho/Wyoming Center for Rural, Frontier and Tribal Child Traumatic Stress. “Here, you have the illusion that it’s safe.”

The deaths of Brenda, Slade and Dylan Groene, and Mark McKenzie and the abduction and abuse of Shasta Groene shattered that sense of safety, residents across the Inland Northwest said. Particularly troubling has been the randomness of a crime allegedly committed by a man who happened to pull off the freeway here.

“It has changed the way I look at strangers,” said Mary Secrest, 54, a Spokane grandmother of two. “I wonder who I am sitting next to at the theater, who is in the grocery line ahead of me. Could it be some deranged killer?”

Parents across the region reported that they’re even more careful about their children than before. Kevin Galik’s 13-year-old daughter, Haley, knows now to check in by cell phone even after a three-block walk to the bus stop.

“I’ve always been concerned, but it got more intense after what happened in North Idaho last year,” said Galik, 53, a wireless service contractor from Spokane. “It’s like part of life, now. It’s just like if she was going to have cereal every morning for breakfast. She knows she has to call dad.”

Law enforcement and other professionals involved in the case confirmed a sense of public unease.

“It’s affected people’s feelings of security in their homes,” said Kootenai County Prosecutor Bill Douglas. “People take more precautions now to lock their doors. The randomness, I think, invaded a lot of people’s sense of security and brought out a lot of change.”

Some in the community reacted in anger. Cheryl Horne, a friend of the victims’ families, started selling bumper stickers and other merchandise with a strong anti-sex-offender theme, including bumper stickers calling for the death penalty for Duncan. Dozens of “Kill Duncan!” stickers have been showing up on cars across Kootenai County. One of the yellow-lettered stickers has been plastered on a “No Trespassing” sign at the driveway leading to the former Groene home.

Along with fear and anger, however, the Wolf Lodge crimes inspired compassion, connection and hope across the region. Hundreds of people donated more than $85,000 to several funds established for Shasta Groene. Kootenai Medical Center was flooded with gifts for the 8-year-old after she was found last July.

“We had an entire classroom filled with balloons and teddy bears and dolls, just out of the blue,” said Lisa Johnson, KMC spokeswoman. “Our security detail turned into gift patrol.”

At Fernan Elementary School, where Shasta and Dylan Groene attended, Principal Lana Hamilton was flooded with e-mails, letters, donations and gifts from nearby and across the country. As rewarding as the outside support was, the internal fortitude of the school’s teachers and staff was even more remarkable, she said.

“The entire Fernan community was affected: students, staff and families,” she said. “One of the things that we learned was that we needed to take care of ourselves and each other. We experienced a unique bond as a result of the events.”

That sentiment was shared by professionals thrust suddenly into a crisis that riveted national attention on North Idaho. In the three days after Shasta Groene was found, KMC’s Johnson made or received 150 phone calls, she recalled. Hordes of national reporters and photographers broiled in a parking lot outside the hospital that July weekend, and some tried to sneak into the building or slip notes to the Groene family. The chaos was made more manageable by a good working relationship among local organizations, officials said.

“This community already had a real good track record of law enforcement agencies working together,” said Don Robinson, supervisor of the Coeur d’Alene office of the FBI. “Our experience in this joint case, really, only became better. If this county ever had another critical incident or crisis like that, I think we’re better able to respond.”

At least one woman, though, said she remains haunted by her personal response to the area’s most notorious crime. Mary Secrest, the Spokane grandmother, believes that she encountered Duncan and Shasta Groene in a Coeur d’Alene Subway sandwich shop the day before they were discovered at a Denny’s restaurant.

“I went in there and there was this dirtball of a guy in line. He was just a mess,” she recalled. “And then I went into the restroom and there was this little girl standing there and she was just washing her hands.”

Secrest, who said she’s “99.9 percent sure it was them,” said she also noticed a red Jeep in the parking lot like the one Duncan was later found to be driving.

But it wasn’t until news of the capture appeared in the paper two days later that Secrest realized who the Subway patrons were. Updated photographs revealed the same small girl she’d seen in the restroom.

“I looked right into this girl’s eyes. It was like she was trying to tell me something,” Secrest said quietly.

Secrest said she didn’t tell anyone about the incident until now because she was embarrassed that she didn’t act. That won’t happen next time, she said.

“If anything like that ever happens again, I’ll say, ‘What’s your name?’” she said. “I had my cell phone. I could have called. I could have kept her in the bathroom … I could have saved her from another day in hell.”

Back in Wolf Lodge, Bob Hollingsworth said he and his wife, Cheryl, have heard rumors that the house where the murders occurred might be demolished. That would be fine with the man who calls himself “an accidental, integral part of this case.”

“It affects you,” Hollingsworth said. “My wife, it affects her a lot. She doesn’t say much, but I think it affects her a lot. She wishes that house was gone over there.”