A look into Seattle’s Ballard Locks

SEATTLE – Life is an upstream struggle.

For proof, watch salmon swim slowly and gamely up the fish ladder at Hiram M. Chittenden Locks – which bills itself as the city’s third-most-popular tourist attraction, and which indisputably represents a fun learning opportunity for adults and children alike.

A few miles northwest of downtown Seattle in the Ballard neighborhood, the locks link the Puget Sound waterways with Lake Washington, the long and lanky body of choppy blue on whose shores lies the University of Washington and in whose southern portion sits well-to-do Mercer Island.

Visitors are treated to an up-close look at how the two locks – the larger one that can accommodate a cruise ship, the smaller one for fishing boats, kayaks and the like – facilitate passage between saltwater (the sound) and freshwater (the lake).

Sidewalks run on all sides of the locks, including over the partially submerged gates when they are closed and the water level is being adjusted. When I was there on a warm, sunny, late-summer weekday, young families, strolling seniors and several just-passing-through bicyclists crowded the site.

The process of enclosing boats in a lock and raising or lowering the water level to match where they were headed took about 15 minutes, and there was no need to worry about missing the “show” because watercraft kept approaching en masse from both directions.

Each year, about 775,000 vessels pass through what’s known locally as the Ballard Locks. Eighty percent of them are pleasure craft, though the commercial traffic that transports sand and gravel, forest products, petroleum products and various other cargo makes a significant contribution to the local economy.

The most interesting passers-by from this tourist’s perspective, however, are the salmon. The fish ladder, reconstructed in 1976 to have 21 steps – up from the previous ladder’s 10 – provides a fascinating window into salmon migration.

There are several windows, actually, in the viewing area beside the ladder, where people were packed tightly to see the large fish (some appeared to be a yard long) as they struggled to return to their freshwater spawning grounds.

According to one of the exhibit’s interpretive signs, salmon typically are born in freshwater riverbeds or streams, make their way to oceans where they spend three to five years, then return to their places of birth to deposit eggs (the females) and fertilize them (the males).

Sockeye, chinook and coho salmon tend to make that homeward journey from June through November, while steelhead – which, unlike the other salmon varieties, sometimes survive the spawning ordeal and repeat the cycle of going to the ocean and then returning – are on the go from January through May.

Unfortunately, salmon’s struggles these days are not limited to their migration. Their numbers are endangered by chemical pollution, dams, development, higher water temperatures and overfishing.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which has operated the Ballard Locks since its inception in 1917, has partnered with the state of Washington and local Indian tribes to facilitate the fish’s safe passage and promote their long-term presence.

Entry to the locks compound is free and includes access to a comprehensive visitors center. There, be sure to catch a 12-minute introductory film, “Where the Activity Never Stops,” which chronicles the site’s history.

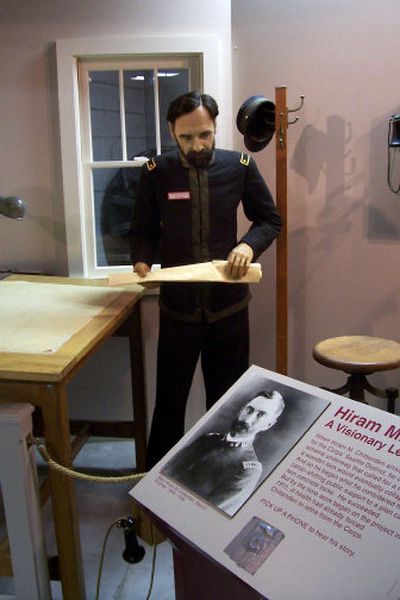

Upstairs in a small museum, learn how the locks’ creator, Chittenden, had the good sense to veto initial plans for a wooden assembly and insist on steel construction.

Chittenden, whose other engineering projects included the road and bridge system in Yellowstone National Park, also had the foresight to order a second, smaller lock at the Ballard site and to cancel plans for an additional lock at Lake Washington.

That ill-advised proposal, according to the museum’s exhibit on Chittenden, would have raised Lake Washington by some 9 feet and triggered future flooding problems.

The museum also contains a functional scale model that allows visitors to operate a lock. It’s not by any means high-tech, but it clearly instructs how such systems make navigation between two separate and uneven waterways possible.