Bush may be forced to reduce Iraq goals

WASHINGTON – “Stay the course” has run its course.

With the firing of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in the wake of a resounding Democratic electoral victory, President Bush opened the way Wednesday to a new approach to concluding the Iraq war – probably on terms different than he’d once hoped.

Attention is expected to pivot quickly to the work of a bipartisan panel led by former Secretary of State James A. Baker III and retired congressman Lee Hamilton that is reviewing U.S. options in Iraq.

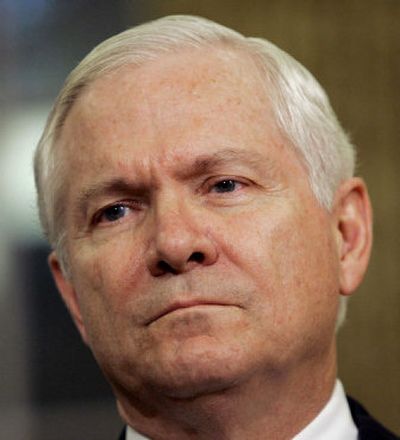

Bush mentioned the Baker-Hamilton commission four times during his press conference Wednesday and said that he’ll meet with its members early next week. And while Rumsfeld was the main architect of the administration’s Iraq policy, Robert Gates, Bush’s nominee to replace him, has been a member of the commission, formally known as the Iraq Study Group.

What Baker’s commission will recommend isn’t known, but three experts advising the panel say support is coalescing around a plan that would involve a new – and final – push to stabilize Iraq by curbing sectarian violence and insurgent attacks and strengthening the weak central government.

Support appears to be growing in Congress and among Bush administration foreign policy specialists for setting firm deadlines for Iraq’s government to make progress in establishing security and restraining the country’s out-of-control militias. Bush so far has opposed timelines.

Baker has said publicly that he favors another big policy switch: opening talks with regional adversaries Iran and Syria, something the White House has refused to do.

Taken together, the expanding role of Baker and Gates appears to signal the return of foreign policy “realists” to positions of influence. Realists stress advancing U.S. interests by working with allies and avoiding idealistic policies such as intervention in other countries to promote democracy. Most of the hawkish group that most strongly backed the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, sometimes known as neoconservatives, are now gone: among them Rumsfeld, former Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz and Pentagon aide Douglas Feith.

Sen. Joseph Biden, D-Del., said Wednesday that the Baker-Hamilton commission’s recommendations could give the White House “the necessary political room to make a radical change” in Iraq policy. “But the question remains, what will a bipartisan consensus (on Iraq) end up being?”

What’s most notable about the evolving Baker plan is what it omits: Bush’s vision of a democratic Iraq that serves as a beacon for the Arab world.

A proposal to stick with the current policy, dubbed “Victory in Iraq,” was quickly taken off the table, said the experts advising the Baker-Hamilton commission. They spoke on the condition of anonymity because Baker has barred them from speaking publicly.

Larry Diamond, a Stanford University scholar who served as a democracy adviser in Iraq in early 2004, said that the U.S. has three strategic goals in Iraq: to prevent parts of it from becoming a terrorist bastion; to stop the country from sliding into all-out civil war; and to set up a stable, quasi-democratic political system that respects human rights.

“The third goal … is just gone at this point,” said Diamond, who’s an adviser to the Iraqi Study Group but didn’t discuss its internal workings.

Even if Democrats end up controlling both the House of Representatives and the Senate, a rapid withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq doesn’t seem likely, either.

“I truly believe the only way we won’t win is if we leave before the job is done,” the president said Wednesday.

On Sept. 4, Democratic leaders wrote Bush and urged him to begin a “phased redeployment” of U.S. troops before year’s end. The signers included Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., now poised to become House speaker.

As of Wednesday evening, however, Democratic leaders hadn’t repeated those demands, and they seem unlikely to vote to cut off funding for U.S. troops in Iraq.

Biden, who’s proposed a different plan that decentralizes Iraq into three largely autonomous regions, said that in the wake of the election and Rumsfeld’s firing, “there is a real possibility of a bipartisan approach to foreign policy.”

Many analysts predict that a precipitous U.S. withdrawal would ignite an all-out civil war that draws in other countries in the Middle East and damage U.S. credibility for years, if not decades.

The idea has petrified Iraq’s Sunni Muslim neighbors – particularly U.S. ally Saudi Arabia.

“All of the people who are talking about civil war now ain’t seen nothing like they’re going to see when we pull out,” said Frederick W. Kagan, a military historian and scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

If U.S. soldiers stacked their arms and began to pull out, death squads would go on a rampage, Kagan said. Mass atrocities would ensue. Iraqi civilians banging on the gates of U.S. bases would be turned away. The horrifying images would be broadcast all over the world.

“Soldiers are going to watch it and be horrified,” said Kagan. “I think the (psychological) damage it’s going to do to the Army is going to be beyond comparison to watching people getting evacuated off the top of the embassy during Vietnam.”

Yet Bush has few other good options in Iraq, where U.S. officials, Middle East leaders and private analysts don’t expect the situation to improve going into 2007.

“The insurgency will continue to grow in strength and popularity,” Nawaf Obaid, a Saudi security analyst who advises the kingdom’s monarchy, predicted in an analysis presented to a Washington conference last month. “All indicators point to increased likelihood of civil war and the disintegration of the Iraqi state.”

Bush could send more U.S. troops to try to secure the country, but there are few active-duty troops available, and the National Guard and Reserve are already overstretched.

Even before the election and Rumsfeld’s sudden departure, Bush and his aides quietly have been making significant course adjustments.

Marine Gen. Peter Pace, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has created a small study group of officers who are reviewing U.S. military strategy in Iraq.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said last week that the United States is planning to increase the size of Iraq’s national army, which, while it has many flaws, is not seen as sectarian as the police force.

The government of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki recently offered to reinstate thousands of purged members of former President Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party to their government jobs.

The two moves amount to implicit backtracking on two of the most-criticized actions the United States took after toppling Saddam: disbanding the Iraqi army and allowing widespread purges of even low-level Baathists. Many U.S. military officers believe those decisions helped ignite the Sunni Muslim insurgency.

Whatever happens, Iraq is certain to shadow Bush for his last two years in office – and beyond.

“We did this to ourselves,” said retired Army Maj. Gen. John Batiste, who commanded the 1st Infantry Division in Iraq from February 2004 to February 2005. “We might as well call it ‘Bushistan.’ “