Use of ‘civil war’ sparks battle outside Iraq

WASHINGTON – The carnage in Iraq is “sectarian violence,” President Bush says. It’s a “struggle for freedom,” the “central front in the war on terror.” It is not, no matter how much it may look like it, a civil war.

Forget the debate over what to do about the war in Iraq. The White House is still debating what to call the war in Iraq. With retired generals, analysts, politicians and pundits increasingly using the term “civil war,” the Bush administration insists that the definition does not fit as part of its latest effort to control the words of war.

To people dying in the streets of Sadr City, it may be just semantics. But the White House fiercely resists the phrase out of fear of its impact in both Iraq and the United States. Defining it as civil war, some strategists worry, could accelerate the conflict and encourage Iraqi factions that remain on the sidelines to join the struggle. And acknowledging that it has become a civil war, they fear, could collapse the already weak support for the mission among Americans.

But the risk for the White House, analysts said, is that once again it will appear out of touch with reality over there and with public perception here at home. For months after the invasion of Iraq, the administration denied there was an insurgency. Then it resisted the notion that there was sectarian violence.

“If they can’t characterize what’s going on in Iraq in an honest fashion, we can’t begin to address the problem,” retired Gen. Barry McCaffrey, who led troops in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, said in an interview.

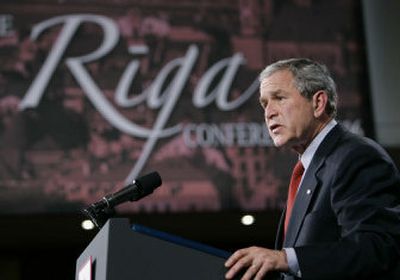

Asked about the matter at a news conference in Estonia on Tuesday, Bush skirted the issue and focused attention on al-Qaida’s role. “No question, it’s tough,” he said. “No question about it. There’s a lot of sectarian violence taking place – fomented, in my opinion, because of these attacks by al-Qaida, causing people to seek reprisal.”

White House press secretary Tony Snow rejected the term “civil war” on Monday because “you have not yet had a situation … where you have two clearly defined and opposing groups vying not only for power but for territory.”

The issue of terminology has arisen periodically for months, especially since the February bombing of the Golden Mosque in Samarra touched off round after round of attacks between the once-dominant minority Sunnis and the majority Shiites who now control the government. The debate has flared more intensely in recent days amid the bloodiest assaults of the war in the Shiite slum of Baghdad known as Sadr City.

The decision by NBC News on Monday to use the term despite White House objections prompted a fresh examination by many in Washington about the nature of the conflict. As MSNBC began flashing the logo “Iraq: The Civil War,” other news organizations staked out positions. The Los Angeles Times noted that it has been calling the violence a civil war since October. The New York Times said it will use the term, though sparingly. The Associated Press, one of The Spokesman-Review’s primary sources of Iraq news, said it is still debating the issue; the Washington Post has made no policy.

The Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines a civil war as “a war between political factions or regions within the same country.” Scholars often further refine that to those conflicts that take at least 1,000 lives. Those who argue that Iraq does not qualify say that a true civil war involves organized military units contesting for territory on behalf of competing governments or quasi-governments.

Polls suggest that a majority of Americans have already settled this debate in their minds – 61 percent of those surveyed in September by NBC News and the Wall Street Journal described the situation in Iraq as a civil war, while 65 percent agreed in a CNN poll and 72 percent in a Gallup poll.

“There’s a good deal of research to suggest that the American public is less willing to use troops to intervene in other countries’ civil wars than in humanitarian-type missions,” said Christopher Gelpi, a Duke University scholar who has studied public opinion in wartime. “So even if the facts on the ground are the same … the label used has a substantial effect on public opinion. That’s why they’re fighting over it.”

Language also has the power to influence events in Iraq, where leaders engage in a similar debate. “If this is not civil war, then God knows what civil war is,” former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi said as far back as eight months ago. But the current prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, adamantly rejects the term, and analysts said his fragile government risks collapsing if it accepts the premise.