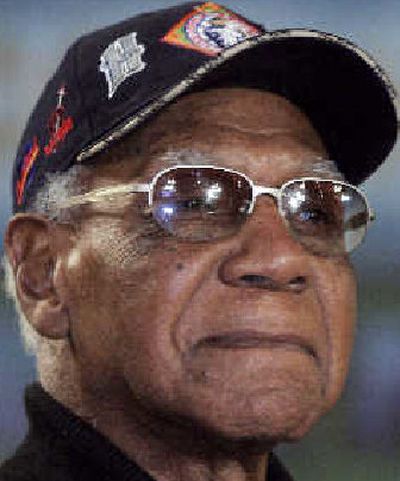

Baseball icon O’Neil dies at 94

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – Buck O’Neil, the warm and witty goodwill ambassador for the Negro Leagues, died Friday night at a Kansas City hospital. He was 94.

A star in the Negro Leagues, O’Neil later became the first black coach in the majors. Baseball was his life – in July, he batted in a minor league All-Star game.

O’Neil had appeared strong until early August, when he was hospitalized for what was described as “fatigue.” He was released a few days later, but readmitted on Sept. 17. Friends said he had lost his voice along with his strength. No cause of death was immediately given.

“What a fabulous human being,” Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson said Friday night. “He was a blessing for all of us. I believe that people like Buck and Rachel Robinson and Martin Luther King and Mother Teresa are angels that walk on earth to give us all a greater understanding of what it means to be human. I’m not sad for him. He had a long, full life and I hope I’m as lucky, but I’m sad for us.”

O’Neil became as big a star as the Negro League greats whose stories he traveled the country to tell.

O’Neil had long been popular in Kansas City, home of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, but he rocketed into national stardom in 1994 when filmmaker Ken Burns featured him in his groundbreaking Public Broadcasting Service documentary “Baseball.”

The rest of the country then came to appreciate the charming Negro Leagues historian as only baseball insiders had before. He may have been, as he joked, “an overnight sensation at 82,” but his popularity continued to grow for the rest of his life.

“He brought the attention of a lot of people in this country to the Negro Leagues,” former Washington manager Frank Robinson said. “He told us all how good they were and that they deserved to be recognized for what they did and their contributions and the injustice that a lot of them had to endure because of the color of their skin.”

Few men in any sport have witnessed the grand panoramic sweep of history that O’Neil saw and felt and experienced in baseball. A good-hitting, slick-fielding first baseman, he twice won a Negro Leagues batting title then became a pennant-winning manager of the Kansas City Monarchs.

As a scout for the Chicago Cubs, he discovered and signed Hall of Famers Lou Brock and Ernie Banks.

In 1962, a tumultuous time of change in America when civil rights workers were risking their lives on the back roads of the Deep South, O’Neil broke a meaningful racial barrier when the Chicago Cubs made him the first black coach in the major leagues.

Jackie Robinson was the first black with an opportunity to make plays in the big leagues. But as bench coach, O’Neil was the first to make decisions.

He saw Babe Ruth hit home runs and Roger Clemens throw strikes. He talked hitting with Lou Gehrig and Ichiro Suzuki.

“I can’t remember a time when I did not want to make my living in baseball, or a time when that wasn’t what I did get to do,” he said in an interview with the Associated Press in 2003. “God was very good to old Buck.”

Born in 1911 in Florida, John “Buck” O’Neil began a lifetime in baseball hanging around the spring training complex of the great New York Yankee teams of the ‘20s. Some of the players befriended the youngster and allowed him inside.

In February 2006, it was widely thought that a special 12-person committee commissioned to render final judgments on Negro Leagues and pre-Negro league figures would make him a shoo-in for the Baseball Hall of Fame. It would be, his many fans all thought, a fitting tribute to the entire body of his life’s work.

But when word came from Florida that day that 16 men and one woman had been voted in, he was not among them. For reasons never fully explained, he fell one vote short of the required three-fourths.

“Shed no tears for Buck,” O’Neil said. “I couldn’t attend Sarasota High School. That hurt. I couldn’t attend the University of Florida. That hurt.

“But not going into the Hall of Fame, that ain’t going to hurt me that much, no. Before, I wouldn’t even have a chance. But this time I had that chance.

“Just keep loving old Buck.”

But among his close friends, few believed that his heart wasn’t really broken.

“It is clear the Baseball Hall of Fame has made a terrible error in not inducting Buck on this ballot,” Missouri Rep. Emanuel Cleaver said. “It is rare that an entire community rallies around a single person, but our city loves Buck, what he stands for and his indomitable spirit.

“Buck O’Neil is a man who has done more than anyone to popularize and keep alive the history of the Negro Leagues.”