Global warming would hit home

If climate change hits North Idaho like several scientists said it might Saturday, a shorter ski season at Schweitzer will be the least of the region’s concerns.

Increased wildfires, more severe droughts and a decrease in unique wildlife might permanently change the landscape and life in a place far away from rising sea levels and dense population.

“We’re being introduced to a new kind of drought,” said Philip Mote, an atmospheric scientist with the University of Washington’s Climate Impact Group. “When we think of drought, we think it’s not raining. But in the Northwest, where snowpack is very important, we can get into a drought if there’s enough snow in the winter, but it melts faster in the spring.”

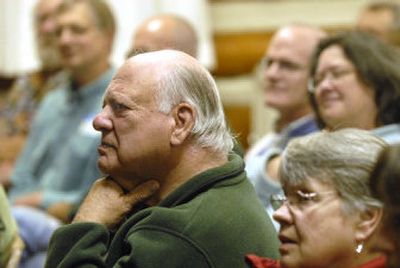

Mote joined several other speakers in a conference Saturday about climate change and how it would affect the ecosystems and economies of Idaho. More than 60 people listened to the presentations, organized by the Idaho Conservation League, ranging from detailed scientific explanations of climate change to ways rising global temperatures could decrease the number of native caribou and increase the population of whitetail deer.

Mote said solid scientific data show again and again that global temperatures are rising rapidly and that humans are the cause.

“My primary goal is to show the science is pretty solid,” he said. “If people want to believe something else, they need to be confronted with the whole body of scientific evidence.”

Mote said climate change likely will mean earlier winters and springs and a smaller snowpack that will cause water supply problems in summer. Less snow, he said, means less water for the Spokane Valley/Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, drier forests that will burn easier and shorter fishing seasons.

“These changes are already occurring,” Mote said. His hydrology models show a trend of decreasing snowpacks over the past few decades.

Drier forests also may mean an increase in mountain pine beetles, which live longer and can do more damage to trees when temperatures are warm, Mote said.

In turn, forests decimated by pine beetles are more susceptible to damaging wildfires, and that will affect wildlife in the West on a large scale, said Sam Cushman, a research landscape ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station.

“Most changes in wildlife will come from a change in vegetation,” Cushman said.

But he took issue with the contention that too much fire suppression over the past 100 years has caused a highly flammable increase in the amount of fuels, causing bigger fires.

In the mountains of North Idaho, forests will become more flammable not because of heavy undergrowth, but because the forest is exposed to moisture and cold temperatures for less of the year, Cushman said.

“It’s not because of fuels. The forest will become more flammable because it’s dry,” he said. “It has increased flammability because of less water and higher temperature.”

More and more people nationwide are becoming aware of global warming, and conferences like this help people understand what’s coming, Mote said.

“It’s going to be interesting to watch,” he said. “There is this kind of constant drumbeat that, yes, climate is changing, and somebody should do something about it.”