Low-fat ice cream can taste whey better

PULLMAN – Researchers are asking a lot of questions at Washington State University.

Does environmental pollution cause disease for generations? What do the earliest galaxies in the universe look like?

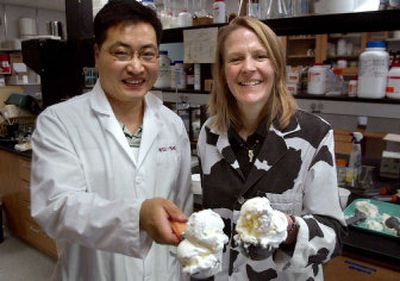

Doctoral candidate Seung-Yong Lim is working on a tastier topic: ice cream.

“A lot of people want to eat low-fat ice cream,” said Lim, in a recent interview at the WSU Creamery. “But the taste is not good.”

Lim is in his fourth year of trying to fix that. A former Baskin-Robbins quality control manager in Korea, Lim is developing a pasty liquid with whey – a byproduct of cheese-making – that improves the flavor and body of low-fat ice creams. The whey paste is more fatlike than dried whey typically used in food products, but it’s also created through an expensive process using hydrostatic pressure and may not be practical at commercial dairies.

Lim came to WSU specifically to study this question, after discovering the school’s food science program and associate professor Stephanie Clark, who has studied the chemistry, microbiology and processing of dairy products. He should be finished in December.

Whey is the translucent liquid produced during cheese-making as milk coagulates. About 90 percent of milk used in making cheese becomes whey byproduct, and the protein-rich substance can create environmental problems when it’s dumped into waterways.

It’s also costly to dispose of, and the dairy industry has focused in recent years on finding ways to reuse whey, ranging from dairy products to animal feed. About 30 percent of the whey now produced in the United States is discarded, according to Dairy Field magazine.

WSU’s food science and human health department has studied other uses for whey. Students recently developed a beverage for a national contest called Whey Cool!ers, and an upcoming study will examine the effects of whey drinks on high-blood pressure.

Lim’s work differs from other uses of whey because of the method of concentrating the proteins in the substance. Using hydrostatic pressure, he squeezes out most of the water and concentrates the proteins. The resulting paste helps create an ice cream with a better feel in the mouth and better body, which means less shrinkage in the freezer.

It’s essentially an attempt to mimic fat solids.

“What he’s trying to do is make the low-fat ice cream a little more like full fat,” Clark said.

The work has practical implications for whey disposal – but also limitations. It could be ideal for a dairy that makes both ice cream and cheese, and that can use the whey from its cheese-making. But most dairies don’t make both.

And using Lim’s method requires expensive equipment, and the product doesn’t have the shelf life of dried whey. It may not make economic sense now for many dairies, Clark said.

Lim’s research has involved lots of complicated science and testing, but it’s also included enough ice cream to make him slightly weary of the dessert.

“I like ice cream, but I don’t like so much ice cream,” he said. “Every day, you eat ice cream. That’s not good.”