Preparedness program maps schools

When a teenager with a gun holed up in a classroom at Spokane’s Lewis and Clark High School three years ago, a computer mapping and school data program let school officials and emergency responders access vital information about the layout of the school within minutes.

More than 2,000 students evacuated to a grassy field next to the school but were moved after the program – called Rapid Responder – brought up a detailed map of the school grounds and photos of the classroom, revealing that the field was in direct sight of the gunman.

“There were lots of things that happened quickly in that situation that can be attributed to Rapid Responder,” said Lewis and Clark Principal Jon Swett.

The Coeur d’Alene School District implemented the same program this year after receiving a $248,000 federal grant to pay for emergency preparations. The district is the first in Idaho to use Rapid Responder.

Every school in the district has detailed information entered into the program, including floor plans, locations of water and gas pipes, photos of classrooms, the views from the windows, student population and building capacity, even the locations of trees and bushes around the school. Also available are emergency plans and other resources like the local sex offender registry.

The password-protected information is accessible via the Internet, or it can be installed on computers or stored in a memory key that can be plugged into any computer.

The information is meant to help in not just potentially violent situations but other emergencies like chemical spills or natural disasters.

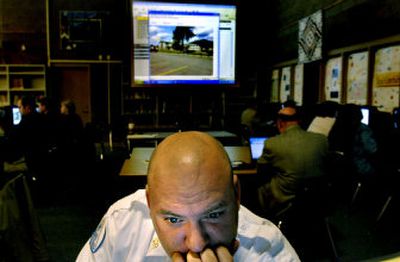

The district held a training session Wednesday at Woodland Middle School, a makeup session for anyone who missed the first training sessions in August.

Three employees – typically the principal, office secretary and head custodian – from every elementary, middle and high school in the district were trained to use the programs, along with representatives from the city and state police, the county Sheriff’s Office and fire and rescue officials.

“The real advantage of a system like this is it really allows responders to be proactive,” district Superintendent Harry Amend said.

Fifteen to 20 years ago, such a program would seem like an overreaction, he said.

“Back then, if you had talked about locking most of the doors, people would have thought that was an overreaction, too,” he said.

But with the string of school shootings in the past decade, things have changed.

“It’s just a society that, in some ways, is not as safe,” Amend said.

Now, programs as detailed as Rapid Responder make sense, and with the role the program played in the 2003 Lewis and Clark incident, “it even makes more sense,” he said.

Prepared Response, the company that produces the program, touts the incident at Lewis and Clark as a prime example of how the program can help in an emergency.

A video on the company Web site features Swett, the Lewis and Clark principal, and Spokane law enforcement officials discussing how the program was used.

The information that law enforcement accessed via the program showed the gunman was in a science classroom. A click of a computer mouse showed how to turn off the gas that flowed to the classroom, preventing a potential explosion.

“It couldn’t have been a more illustrative example of how the system works,” said Warren Conner, vice president of marketing for Prepared Response.

The program’s emphasis on the importance of building location and sight lines from classrooms complements what Amend said the district learned during an incident last spring near Bryan Elementary. A gunman was in a duplex on SeventhStreet and Harrison Avenue, a unit with a view of the school.

“Half the school was in the sight line, unobstructed,” he said.

School officials and law enforcement could have learned that almost immediately using the Rapid Responder program.

Conner points out that the program has also saved schools thousands and thousands of dollars from more innocuous things like broken water pipes.

When students at a Spokane school broke a water pipe in the gymnasium while attempting pull-ups, Conner said, security officers were able to find the water valves and turn them off almost immediately.

Excess water on the gym floor could have ruined it, costing the school up to $100,000, Conner said.

The Coeur d’Alene School District’s federal grant covered the costs of implementing the program and training school employees. No new costs are anticipated unless a new school is built.