NASA ready to reveal future Hubble plans

WASHINGTON – As NASA learned when it canceled a planned shuttle mission to keep alive the Hubble Space Telescope almost three years ago, its orbiting source of jaw-dropping intergalactic images and deep insights into the early days of the universe had become something of an astronomic rock star.

The scientific and public response was overwhelming: The 14-year-old Hubble had to be saved before its batteries and gyroscopes failed, and NASA was seriously misguided for refusing to send a shuttle crew to keep it running. This view was strongly endorsed by an expert panel convened by the National Academy of Sciences in late 2004.

Soon after, Michael Griffin became NASA administrator and agreed to reconsider the Hubble mission. On Tuesday, 18 months later, he will announce whether the telescope will be repaired or will be allowed to gradually run out of steam.

NASA said Friday that a series of events and briefings will follow the announcement at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. – the kind of activity that often accompanies a decision to go ahead with a big mission. But agency officials said that no decision had been reached and that Griffin will study the pros and cons over the weekend.

“Every scientist on the face of the globe, and many people in the general public, are watching this, looking forward to a decision,” said Mario Livio, head of the science program at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, which manages the Hubble’s scheduling and research for NASA. “I’m cautiously optimistic, but there are so many factors involved.”

For Griffin, it is a tough choice – balancing the undeniable success of the Hubble against the equally undeniable risks to the astronauts who would fix it, as well as the unforgiving schedule of shuttle flights needed to complete the international space station.

The decision by his predecessor, Sean O’Keefe, to scrub the Hubble repair mission was made after the 2003 Columbia disaster, when it was not clear when the shuttles would get back into space.

Griffin has often said that he believes the telescope is one of the great scientific instruments of all time and that it deserves to be repaired.

“If we can do it safely, we want to do it,” Griffin said at a September briefing after the successful landing of the space shuttle Atlantis. “But we have new constraints on … the space shuttle system. We have a new understanding of its fragility and vulnerability.”

Among the major constraints are that the space shuttle fleet is aging fast and that NASA is eager to finish assembly of the space station by 2010, so the three remaining spacecraft can be retired. A mission to Hubble could interfere with the schedule.

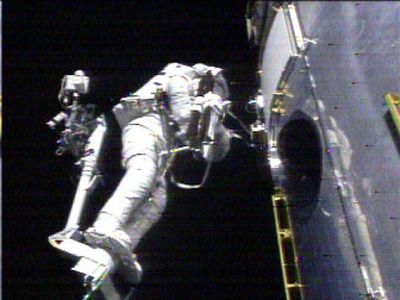

After two fatal shuttle disasters, NASA is also increasingly focused on safety and on having backup systems for crews if their spaceship gets damaged. In theory, the international space station is the standby shelter for a spacecraft in trouble, but it would be unreachable on a flight to the Hubble. That is because the orbits of Hubble and the space station are very different, and a shuttle launched to the Hubble would not have the fuel and power to shift orbits to reach the station.

As a result, the crew of a Hubble-bound shuttle has only about three weeks’ time to repair any damage to the spaceship. That would hardly leave time for the final contingency, preparing and launching a second shuttle for a rescue mission.

“We’ve had three successful shuttle missions since Columbia, and we’ve learned a lot about inspecting and repairing the vehicle,” said NASA spokesman Allard Beutel. “So we have a lot more capability and flexibility, but clearly some safety issues remain.”