Deal would return water to long-dry California river

A historic settlement outlining the most ambitious river restoration project in California’s thirsty history was filed in federal court Wednesday, the first major step in an effort to return year-round flows and a long-destroyed salmon run to the Central Valley’s once-grand San Joaquin River.

The agreement ends an 18-year legal battle over the river, parts of which were reduced to a sandy skeleton a half century ago after most of its Sierra-fed waters were diverted to a million acres of San Joaquin Valley agriculture.

“The magnitude of this restoration effort – returning water and salmon back to 60 miles of dead river – is virtually unprecedented in the American West,” said Hal Candee, a Natural Resources Defense Council senior attorney who helped file the 1988 lawsuit that produced the settlement after years of negotiations.

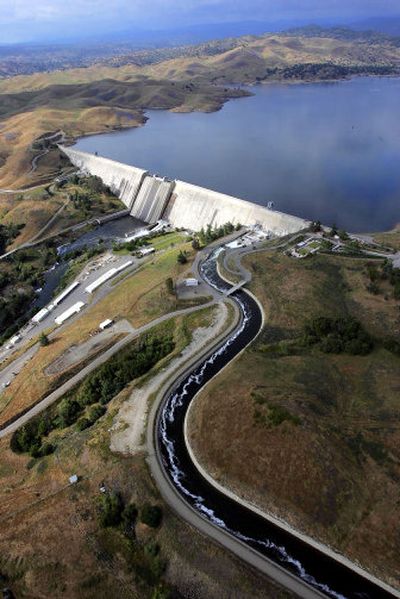

The agreement between the federal government, growers and environmental groups will reduce diversions from the river by an average of 15 percent, releasing enough water from Friant Dam near Fresno to revive a spring Chinook salmon run that was completely wiped out after the dam was built in the 1940s.

Fish passageways and screens will be constructed, the river channel will be improved in some areas and levees strengthened to contain the increased flows.

The project will take years and, according to estimates, will cost between $250 million to $800 million, depending on how extensive the levee work is. Funding will come from growers, the state and the federal government, which operates Friant Dam.

State Department of Water Resources Director Lester Snow called the project “an incredible opportunity” while, in a statement, Assistant U.S. Interior Secretary Mark Limbaugh termed it “monumental.”

The settlement lays out various ways to help farmers make up for the supplies they will lose to the river. In wet years with high San Joaquin flows, for instance, growers will be able to buy discounted water from the federal government to store for future use. It’s likely they also will buy water from other irrigation districts that don’t draw from the San Joaquin.

“We’re very encouraged that the terms of the settlement are a balanced approach for river restoration and water supply,” said Ronald D. Jacobsma, consulting general manager of the Friant Water Users Authority, representing the growers.

Not everyone was celebrating, however. While officials were praising the agreement at news conferences in Sacramento and at Friant Dam, representatives from irrigation districts not involved in the lawsuit were in Washington, expressing their concerns in Congress and at the Interior Department.

Those districts take water from tributaries of the San Joaquin and parts of the river not covered in the settlement. They worry that the return of the spring run, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, could trigger protections that would affect their hydropower production, force them to give up water and install costly fish screens or passages.

The settlement must be approved by U.S. District Judge Lawrence Karlton, who has presided over the case since it was filed. Attorneys expect that to happen within a month.