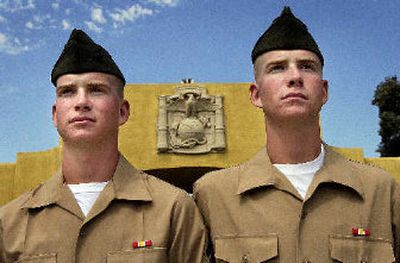

Two good men

After graduating from boot camp, twin brothers Robert and Matt Shipp, from Hauser Lake, know they have what it takes to be Marines

A closed sign hung in the window of the little Coeur d’Alene barber shop when Matt and Robert Shipp arrived Tuesday afternoon, a day after returning home from boot camp.

Although their hair was barely longer than toothbrush bristles, the 18-year-old twin brothers from Hauser Lake needed a trim. Not just any trim, but the trademark “high and tight” buzz cuts worn by U.S. Marines.

After 13 sweaty, grueling weeks, the Shipp twins had earned the right to be called Marines. They wanted to look the part during their few days at home.

Richard Bird, owner of the Best Avenue Barber Shop, kept his business open for the twins. “I’ll stay late for these guys,” said Bird, who served in the Marine Corps four decades ago. He also refused payment.

For the twins, this is all part of realizing their dream of becoming Marines. It will be at least another four months before they are deployed overseas to begin the hard work of fighting the nation’s wars in Iraq or Afghanistan. For now, they are simply enjoying unexpected doses of respect and gratitude – the free haircut, the standing ovation at a San Diego Padres baseball game, the modest military discounts, the thumbs up gestures and back pats from strangers.

“It feels good,” Robert said, after recounting some of these instances he and his brother have experienced since graduating from boot camp Sept. 15.

The twins are happy to be home but eager to get on with the business of training for war. On Tuesday, Pfc. Robert Shipp will return to California for infantry training at Camp Pendleton. A week later, Pfc. Matt Shipp will arrive at the base to begin learning how to direct artillery fire. For the first time since birth, they will be separated, but they expect to be able to see each other on Sundays. Both are hoping to try out for reconnaissance training, the toughest offered by the Marines.

According to their recruiter, the twins have a “95 or 96 percent” chance of being deployed to Iraq once they finish training. Although the American public is divided on the merits of fighting this war, the Shipps are eager to serve their country. Like countless generations of young men before them, the twins want to prove themselves in combat. If anything, boot camp only boosted their desire to experience battle.

“I want to see action,” Matt said.

By joining the Marines during a time of war, that’s almost a given. The Marines, the smallest branch of the military, make up about 15 percent of U.S. armed forces personnel serving in Iraq. They’ve served in the toughest battles. This fact is borne out in Pentagon statistics: Nearly one in three Americans killed in Iraq has been a Marine.

Like countless generations of mothers, Leslee Shipp doesn’t like hearing her sons talk about going off to war. She chokes up with every little reminder that her twins – whom she still calls “my babies” – could soon be sent overseas with rifles and helmets. She even got teary when the family visited SeaWorld and her sons were applauded for their service in the military.

But Leslee and her husband, Dennis, are also immeasurably proud. Their sons seem tougher and much more serious. They have a sense of direction, Dennis said. Both boys are talking about making a career out of the Marine Corps. Matt is thinking about eventually becoming a helicopter pilot. Robert aims to earn his sergeant’s stripes within four years, then go to officer candidate school and eventually learn to fly fighter jets. Lofty goals, for sure, but Dennis and Leslee are thrilled.

“I think they’re going to go far,” Dennis said.

Not that long ago, Robert wasn’t even going to finish high school. He dropped out for a while but returned when he learned he needed a diploma to enlist alongside his brother.

Dennis Shipp, who had previously scorned tattoos, has been so impressed by the transformation, he had the Marine Corps logo and his sons’ names inked permanently on his bicep. Although the twins didn’t earn the right to be called Marines until finishing boot camp, Dennis had no doubts. He got the tattoo several weeks before they graduated.

This pride is always competing with fear. Leslee tries to avoid news of the war. Dennis said he now follows the news intensely, hoping to learn what his sons might soon face. Months of training remain before any overseas deployment. For now, Dennis and Leslee are embracing the sliver of a chance the boys might not end up on the front lines in a desert halfway around the world.

“They want to go to Iraq. I don’t want them to. I’d rather see them go to Japan or someplace like that,” Dennis said.

♦

Leslee and Dennis, along with their younger son, C.J., first-born daughter, Lacey, and Matt’s girlfriend, Jessica Whetstine, traveled to San Diego earlier this month to attend boot camp graduation. All flavors of families filled the metal bleachers to watch the 631 recruits in Company K, 3rd Battalion – nicknamed “Killer Kilo” – receive the Marine Corps eagle, globe and anchor emblem. Many, like the Shipps, who operate a restaurant and resort on Hauser Lake, were solidly middle class. One set of parents arrived in the back of a gleaming black limousine. Others wore the deep, dark tans of people who spend their days picking fruit or working fields.

As the families waited, the recruits assembled on the opposite side of the massive sea of asphalt known as the parade deck. Girlfriends stood impatiently, chewing gum and twirling locks of streaked hair. An American Indian man with a fresh straw hat towered above many in the crowd. He stood silently staring at the distant recruits.

When the young men began marching in double time past their families, a silver-haired grandmother started sobbing and nearly collapsed. A dry, hot breeze blew over the asphalt parade deck, carrying the faint odor of sweat and canvas and prompting a young woman to proclaim, “Ooh! They smell so good!”

Leslee Shipp was in tears when she spotted the flag of platoon 3019. Out of seven platoons graduating that week, platoon 3019 was named honor platoon. They did better than the others at things recruits must master, such as shooting, climbing walls, running, swimming, marching and reciting Marine Corps history.

Even though all the recruits were nearly bald and wore the same uniforms, Leslee had no trouble spotting Matt and Robert. “There’s my babies!” she shouted, barely audible over the roar of the crowd. Dennis pumped his fist high into the air. “Yeah! Yeah! That’s my boys!”

In the days leading up to graduation, Leslee grew increasingly anxious that her sons would become not just Marines, but robots. This fear evaporated seconds after she reached her sons. She hugged them. They hugged her back.

“I’m sorry,” she said, wiping mascara from the lapel of Robert’s crisply ironed shirt, “Just look at your uniform.”

“We made it,” Matt said.

“We’ve been reborn,” Robert added. “It’s weird, you look at the new recruits now and you feel years older than them.”

Dennis beamed. After a few minutes, he called Robert and Matt to his side and rolled up his shirt sleeve, revealing the large tattoo. Robert’s jaw dropped. “That’s badass!”

The twins announced they are also planning to get matching “Brothers in Arms” tattoos.

Later in the afternoon, Matt and Robert were given several hours of “liberty” to walk the base with their family. Matt escorted his girlfriend. Leslee reached for Robert’s right arm for an escort. He pulled it away and offered his left. “I have to salute with my right hand, Mom,” Robert explained.

As they passed an office, a sergeant shouted through the open doorway. He ordered Matt to stop. “How did they teach you to escort a young woman?” he yelled.

Matt’s face reddened. He quickly corrected his elbow to the required 90-degree escort angle. It was a reminder that even while on leave, the twins were now Marines and would be for every second of at least the next four years. Escort stumble aside, Matt couldn’t be happier about finally becoming a Marine. It didn’t really sink in, though, until a few hours after Matt received his Marine Corps pin. Matt was walking back to his barracks when a platoon of new recruits jogged past. The recruits yelled out to Matt, “Good afternoon!” Recruits must acknowledge any Marines they see.

Matt was all smiles. “That felt good,” he said.

Robert and Matt wolfed down double cheeseburgers that afternoon. They began to loosen up and tell stories from their training, like the time they met a Marine who was injured while fighting in Iraq. He dove atop a grenade to save his fellow Marines. He survived, but “lost 70 percent of his blood supply,” Robert said.

Leslee sighed. “I don’t want to hear that,” she said.

Matt and Robert Shipp aren’t the only members of their family changed by the Marines. Their parents and siblings – like hundreds of thousands of other military families across the nation – must cope with the intense joys of reunions while dreading inevitable departures to unknown, possibly dangerous places.

“I don’t want them to leave,” Leslee said less than an hour after her sons became Marines. “I’m freaked. Those are my babies.”

C.J., the twins’ 14-year-old brother, sat quietly, occasionally patting the backs of his big brothers. “I missed you guys,” he said repeatedly.

After boot camp, the twins spent the weekend with their family at a beachside hotel in San Diego. They slept on soft mattresses and enjoyed not being awakened with a shout or having to make their beds each morning. Robert, despite repeated pleas from his mother, promptly resumed his chewing tobacco habit – during boot camp, he secretly indulged by sticking a wad of coffee grounds between his lip and gum.

Tuesday was their first morning back at home. The twins woke at sunrise for a run around Hauser Lake. Then they followed the orders of their drill instructors and returned to high school to thank their teachers and mentors.

Matt’s shop class teacher at Lakeland Senior High School in Rathdrum, Corey Pettit, briefly paused class to talk with the twins. He shook their hands and asked about boot camp and what happens next. Robert and Matt smiled and, in characteristic fashion, kept their answers short.

“It’s been great,” Matt said. “We love it.”

“It’s easy,” Robert said, grinning.

Pettit had a serious look when he said goodbye to the Shipps. “Take care of yourselves, all right?”

When Robert returned to his alma mater, Mountain View Alternative School, he was mobbed by old friends and teachers. Lara Carr, who works at the school, hugged Robert. Her son, Lance, is also in the Marines and was expecting to be deployed to Iraq late last week.

“Please be safe,” Carr told the Shipp twins, who were standing ramrod straight with their hands clasped behind their backs. They nodded and smiled.

Robert and Matt are fairly quiet. They’re known more for listening than talking, but the young men become animated when they discuss their recent training or their growing eagerness to use their new fighting skills.

At a community potluck Thursday night at the family’s resort on Hauser Lake, the twins were approached and congratulated by a stream of older men who once served in the Marines. Some of the men pulled the twins aside, leaned in close and told stories of past battles, of good times with fellow Marines.

By the looks they wore, Robert and Matt were enthralled. They sucked up the war stories and probed for details. Meanwhile, the twins’ parents stood nearby holding each other tightly and keeping a close watch on their boys.