Death stuns family, friends

The man killed in a confrontation with a police officer on March 24 was a “workaholic” heavy machine operator from Georgia who would travel as far as Alaska for a good job but ended up homeless and jobless in Spokane, according to friends and family.

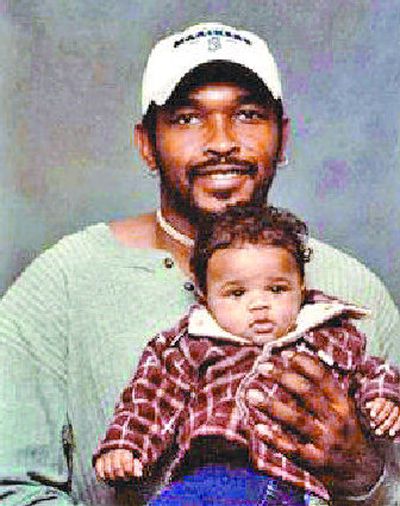

Jerome Alford, who was 33, was buried April 1 after a funeral in his hometown of Thomaston, Ga., his younger sister, Lashanda Alford, said.

He left behind a 3-year-old son in Toronto and a wealth of questions for those who knew him best.

“This thing doesn’t make sense to me,” said Michelle Jakma, of Toronto, who takes exception to news reports that her son’s father could have been mentally ill.

“How do I tell my child that his father was killed by a police officer and not have him have a negative view against them?” Jakma asked.

The Spokane County Sheriff’s Office is investigating the shooting. Little information has been released. Spokane police Sgt. Dan Torok struggled with Alford during a confrontation downtown the morning of March 24. Torok radioed for help, and the confrontation ended with Alford shot in the chest.

Photographs taken of the officer shortly after the struggle show him bleeding. Torok has returned to work after taking a brief administrative leave.

Jakma said she met Alford on the Internet in early 2002. The two carried on a six-month conversation online and by phone before she traveled to see him in Arlington, Texas, where he worked for Cutler Hammer, a manufacturer of electrical equipment.

“As long as I have known him, he was a very hard worker,” Jakma said. “When he wasn’t working, he felt inadequate and frustrated.”

He visited her several times in Canada in 2002. His son, Darian, was born in July 2003, and Alford saw him during a visit that November. It was the last time Jakma and her son would see Alford. It had become obvious to her that they “would not have made great parents together.”

“The end result is he gave me a beautiful gift,” Jakma said of their son.

About the time Alford met Jakma during an Internet chat, he also struck up an online relationship with Shelly Peterson, of Spokane.

Peterson sent Alford classified ads about jobs in the Inland Northwest. In 2003 she met him in person after he moved to Moses Lake, where he had taken a job. She said he told her he had worked for a time in Seattle, Portland and Alaska.

She saw him off and on, and during this time she knew of his trips to Canada.

Peterson was struck by Alford’s polite nature and his need to work.

“There wasn’t a mean streak in him,” she said. “He was very smart, very good-looking. He probably had no problem meeting women. He was friendly and respectful.”

The last time Peterson saw Alford was in August.

“He showed up at my door and said he was homeless,” she recalled. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Alford told her he was staying at the Union Gospel Mission, but he didn’t like it there, and he told her he was moving out even if it meant sleeping under a bridge.

“I told him if it ever came to that to give me a call,” she said. He never did.

Peterson said Alford appeared changed on that last encounter. “Still polite, kind and respectful,” she said, “but he was different. I thought he was a little paranoid.”

She said it surprised her to hear that he had fought with a police officer.

“Punching a cop and running is definitely not in his character,” she said.

Peterson said she didn’t know how he came to be homeless, either, although he commented to her that, “he wasn’t going to kiss butt for a few bucks.”

In early August, Alford moved into the Truth Ministries homeless shelter on East Sprague. The center’s directors, Julie and Marty McKinney, said he was clean-shaven, neat and always awoke at first call to report for work at Labor Ready, a temporary employment company.

“Then five months ago, he started looking scruffy, letting his hair and beard grow,” Marty McKinney said. “He stopped getting early wake-up calls. I don’t think he was going to Labor Ready.”

Though Alford had been cited by a Spokane police officer on Dec. 16 for public consumption of alcohol not far from where he later died, McKinney said he never had a problem with Alford, calling him quiet and introverted. He followed the rules and never appeared to be high on alcohol or drugs.

“But then, I was never in a situation where he was backed into a corner,” McKinney said.

Julie McKinney said that since the death of Otto Zehm, a mentally disabled janitor who died after a confrontation with Spokane police in March 2006, most of the homeless men she encounters at Truth Ministries do not trust the police.

“When a police officer says ‘stop,’ I can tell you, most of the guys in here would keep going,” she said. “They’ve seen things that freaked them out.”

Alford was born in Thomaston on Dec. 8, 1973, to a single mother who died of cancer in 1980, Lashanda Alford said. Jerome, who was one year older than Lashanda, was the most protective of her.

He earned his general equivalency diploma and served in the Georgia National Guard for a time, she said. Her brother “loved country music.” He was “quiet, didn’t cause any trouble, and wanted to get out of Thomaston.”

About 100 people, including his sister and three surviving brothers, attended Alford’s funeral on Saturday at Springfield Baptist Church.