Bills envision national site to honor labor leader Chavez

There are national historic sites that honor the contributions of Revolutionary War heroes, commemorate the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln and even preserve the home of playwright Eugene O’Neill, but none that recognize a Hispanic.

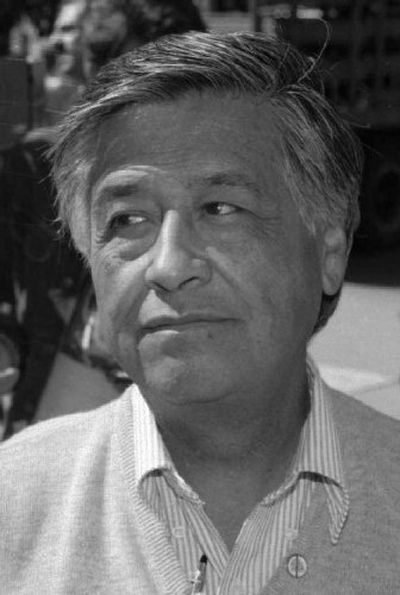

That may be about to change. The late labor leader Cesar Chavez is the focus of companion bills in Congress that would provide funds for the National Park Service to study how to honor Chavez: Is his story – decades spent unionizing and improving the working conditions of farmworkers – best told with a national trail, a historic site or a traditional landscaped park?

The bipartisan bills are under consideration for the first time, despite previous attempts to nudge the proposal out of committee in both houses of Congress, said Rep. Hilda Solis, D-Calif., the legislation’s House sponsor.

If the idea is approved, Park Service social scientists will consult with community leaders and make a recommendation to Congress, which has the sole authority to create a park.

The proposal to honor Chavez is not without its opponents. In addition to those who object to the expansion of federal lands and holdings, other critics say Chavez’s legacy is too unsettled.

In his congressional testimony on the bills, Joe R. Hicks, vice president of the Los Angeles-based civil rights group Community Advocates Inc., said there is no national consensus about Chavez’s contributions.

Solis said she was puzzled by opposition and said recognition for Chavez and Hispanics was overdue.

“We’re the largest minority population; we’re almost not a minority anymore,” she said, adding that her bill is likely to move out of committee at the end of the month.

Chavez was born near his family’s farm near Yuma, Ariz. He and his family became migrant farmworkers after losing their land in the Depression. They relocated to California, and Chavez eventually settled in east San Jose.

Beginning in the 1950s, Chavez worked to organize field workers and formed the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers. His efforts to improve working conditions in the fields led to the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975, which, among other things, protected farmworkers’ right to organize.

A follower of the nonviolent principles of Mohandas K. Gandhi, Chavez led strikes and boycotts. He sometimes fasted as a form of protest. His campaign to boycott table grapes became a nationally supported movement that lasted five years.

Chavez, who was nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize, also worked to reduce pesticide use, became a vegetarian and lobbied for animal rights. He died in his sleep in 1993.