Trial opens for ex-standout

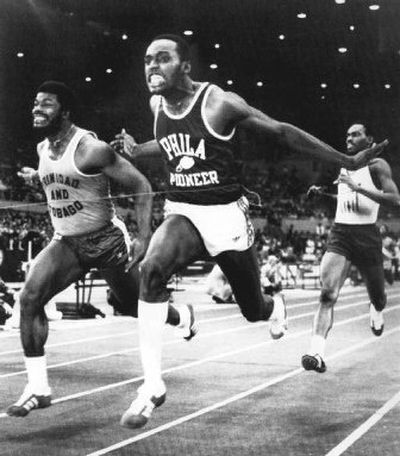

NEW YORK – The last time Steve Riddick’s fate hung in the balance, there were thousands of roaring fans on hand, and he rewarded their shouts with a gold medal in the 400-meter relay in the 1976 Olympics.

This time, his audience will be small, but the stakes are higher. Fifteen jurors began hearing evidence Thursday in a trial to decide whether the track coach goes to prison for bank fraud.

The former sprinter is among four people fighting charges that they were part of a ring that conspired to cash $5 million in forged or counterfeit checks over three years.

The case has already snared another Olympic medalist. Disgraced sprinter Tim Montgomery pleaded guilty Monday to cashing some of the bogus checks in Virginia on behalf of the scheme’s masterminds in New York. He could be sentenced to more than three years in prison.

Riddick is hoping for a better outcome. His attorney opened the trial by saying his client was innocent, unwittingly drawn into the scheme by Montgomery, his one-time protege and coaching client.

In a surprise twist on the trial’s first day, Riddick’s defense lawyer Bryan Hoss said Montgomery had fallen in with scam artists and convicted drug dealers following his implication in the BALCO steroid scandal, then allowed himself to become wrapped up in their criminal schemes.

“Tim Montgomery started brokering kilo-quantity transactions of drugs with these people,” Hoss said.

He did not elaborate and would not comment to reporters afterward, citing a judge’s instruction not to talk to the press.

Federal prosecutors also would not comment, but they appeared displeased that the allegation had been raised.

Montgomery has not been charged with any drug offense, nor had there been any previous indication in the year-old case that drugs were involved.

Montgomery’s attorney, Timothy Heaphy, told the Associated Press that any accusation of drug involvement was false.

“Mr. Riddick is under intense pressure, as he is facing serious federal charges. People in that situation frequently do and say desperate things,” Heaphy said in an e-mail. “Tim Montgomery is surprised and disappointed that Mr. Riddick has chosen to defend himself by making desperate and outlandish allegations like those made by his counsel in this trial.”

Prosecutors contend that the check-cashing scheme was the brainchild of Douglas Shyne and Natasha Singh, a New York couple whom Assistant U.S. Attorney E. Danya Perry described as career fraudsters.

Both have pleaded guilty, along with several others in the case, and Singh is scheduled to testify for the prosecution.

She is expected to outline a scheme in which she and other key conspirators forged or counterfeited checks worth hundreds of thousands of dollars between 2002 and 2005, then recruited accomplices to cash them in exchange for a percentage of the proceeds.

Being tried along with Riddick are Nathaniel Alexander, a businessman who shares office space with the coach in Norfolk, Va., and two New Yorkers, Naresh Pitambar and Roberto Montgomery, who is not related to the track star.

All four claim they were duped by acquaintances into cashing fraudulent checks they thought were legitimate.

“My client sitting here is an innocent man,” Roberto Montgomery’s attorney, Thomas Nooter, told jurors. “He’s an innocent victim of fraud.”

Lawyers for the four men also assailed Singh as a proven liar willing to implicate anyone in an attempt to win a lenient prison sentence.

The trial is expected to resume next week.

After running the winning anchor leg in the relay at the Montreal Olympics in 1976, Riddick lost a chance to compete again when the U.S. boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

He was a head track coach at Norfolk State University in Virginia but lost his job there amid a scandal over misappropriation of school travel funds.

Riddick later became an elite professional coach, training Montgomery and Olympic champion Marion Jones.

Bank records indicate Jones was among those who received checks from one of the accounts, but she was not charged.