Bringing sprawl to California

PALM DESERT, Calif. – Near the 18th hole of Bighorn Golf Course here, Idaho tycoon Duane Hagadone laid out his vision for a dream home to his architect. It would be set high on the mountain rising near the green, yet be so inconspicuous that he’d have to point it out to golf buddies.

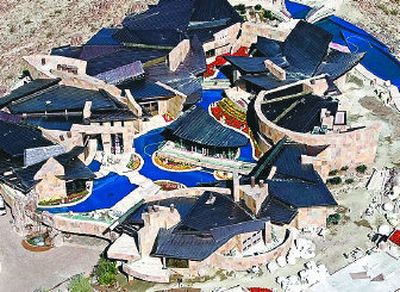

The $30 million-plus home would feature a copper roof that mimicked the mountain ridge, while its walls would be molded from rocks on the hillside.

The architectural plans and model so dazzled city officials that they granted Hagadone an exemption from an ordinance that caps hillside homes at 4,000 square feet. Hagadone’s castle would be eight times that size – 32,016 square feet.

Before that vote in 2004, one City Council member envisioned write-ups “in every architectural magazine around the world”; another said he already had inquired about using this “jewel in our crown” for fundraising events.

“We’ll all be bragging about it,” a third council member said.

Instead, the home has brought a load of grief for this city. Set on a prominent ridgeline and visible from miles away, the house resembles a wayward space station parked amid the foothills.

Hagadone and his representatives declined interview requests. But upset residents have flooded the city with e-mails, branding the house “an unsightly scar on the hill,” “a blight,” “a monstrosity” and more.

“We had an untouched ridgeline, untouched,” said resident Larry Sutter.

Residents complained that their views of the Santa Rosa Mountains, which enfold the city like a clamshell, had been ruined. At dusk, the bare, unlit peaks are silhouetted against the desert’s twilight hues, and residents dreaded how the house would look lighted up at night.

The outrage crescendoed last summer when city officials discovered that Hagadone had graded 64,000 square feet – double what the city had approved – to add unauthorized gardens, a sports court, koi pond and sidewalks.

Some residents demanded that Hagadone rip out unauthorized additions.

“The natural beauty of the desert and the mountains should be there for everyone … not just the few super rich,” wrote James C. Owens. “Have the guts to tell Mr. Hagadone no! No! No!”

Hagadone, 74, lives large.

Lady Lola is a 205-foot yacht Hagadone had custom-built with a floating 18-hole golf course so he could play while cruising around the world with his wife, Lola.

Golf tees sprout from the deck for Hagadone and friends to hack over the water toward 18 buoys his crew anchors at various distances. A supply vessel follows, toting a helicopter and landing pad, several speed boats (to retrieve floating golf balls), sailboats, kayaks and a three-person submarine.

“We’re a very active family. We love water sports,” Hagadone told Showboats International yachting magazine in 2004. “No yacht really gives you the opportunity to carry a full complement of toys.”

His extensive holdings in Coeur d’Alene, which include restaurants, condominiums and a golf resort, have led some critics to dub the town “Coeur Duane.”

Hagadone raised hackles in the Inland Northwest a few years ago by proposing to replace two blocks of its busiest downtown street with a $20 million garden honoring his parents, but he dropped the idea.

Hagadone wasn’t always rich, according to his biography on the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans Web site.

He dropped out of college to sell advertising for the eight-page daily Coeur d’Alene Press, where his father had risen to publisher. After his father died at age 49, Hagadone became publisher and, later, owner of the Press and 18 dailies and weeklies in Idaho and Montana.

In 2004, Hagadone sold his boats for a reported $90 million and bought a plot of land at the Bighorn club.

The home’s original design featured five wings with interior streams and aquariums. It had his-and-her lap pools, an infinity-edge pool, and patios and terraces. Natural light would flood in from more than 110 windows and glass doors – some as large as 80 square feet.

On the entrance level were a huge garage for cars and golf carts, servants’ quarters, an elevator and a food preparation kitchen big enough for an audience.

As Hagadone’s home rose, residents dubbed it “the flying saucer” and “Neverland Ranch.” Blinding glare from the desert sun glanced off the floor-to-ceiling windows of Hagadone’s office, a round building in front of the main home.

It is “like a lighthouse with one major difference – there is no public benefit from its location,” wrote Jane and Paul Mueller, who live nearby, to city officials.

Only a handful of residents expressed support for the project.

Bighorn resident Edward Burger said it would be Palm Desert’s equivalent of Bob Hope’s home, built in nearby Palm Springs on a less prominent peak. “I’m proud to have it in my community.”

During an inspection last summer, Palm Desert associate city planner Tony Bagato discovered that initial construction blueprints understated the home’s square footage by nearly 13,000 square feet: It was actually 44,870 square feet. But Hagadone had built beyond that, grading land for additions not approved by the city.

Hagadone’s representatives called it a mistake and blamed their initial engineers – since replaced – for miscalculating the size. They submitted permit applications to cover the additions.

Oct. 26 was the day of the City Council showdown over the mansion.

Council members expressed frustration about their limited options.

“The first time I approved this, I didn’t think I was approving anything that could be seen over the ridgeline,” said Councilman Richard S. Kelly.

Once something was built, Kelly said, he couldn’t imagine the council demanding the applicant tear it down.

Councilwoman Jean M. Benson asked why Hagadone should be granted anything else, considering “all that stuff he’s done illegally already.”

“We take some poor guy that doesn’t have a nickel and make him tear down a house and rebuild it because he did it without a permit,” she said. Hagadone’s representatives “stood up there and blatantly lied to us.”

City Attorney David Irwin said the original permits contained no provisions specifying that the house wouldn’t be visible. With or without the new permits, Irwin said, “we have very limited ability to impose conditions on the original permit that was issued.”

Hagadone addressed the council, telling members that he hadn’t broken any promises.

“I certainly have not ever proposed or commented that the building would not be seen at all,” Hagadone said.

Hagadone urged the council to approve the sports court and other additions immediately, saying crews were working to finish the house within a few months. He promised to work with a special aesthetics committee appointed by the council if they gave the go-ahead.

“When you’re my age, you don’t want to miss another winter in the desert,” he said.

Mayor Jim Ferguson sided with Hagadone.

With Benson dissenting, contending they were being “blackmailed,” the council voted 3-to-1 to issue the additional permits.

Some residents now say the home is less offensive with the $700,000 that Hagadone says he has spent to make it less noticeable.

Gloria Petitto, 80, whose home was built in 1956, said that instead of the majesty of “God’s nature” she could see from every room, she now sees the Hagadone mansion.

They have “no consideration, no care for anybody else; they just want to be high up and look down,” she said.

“I’ll tell you,” she added, that’s “what money does for you.”

The City Council recently approved an ordinance to prohibit building on or across ridgelines for new lots. But it appears that exceptions can still be made, just as was done for Hagadone.

Hagadone has begun moving into his dream home. The lights have kicked on for the first time on the mountain, pouring from the glass walls.

The sight fills resident Waldo H. Shank with fury “to look up on that ridge all lit up like a carnival each night and know that it was all accomplished by their pushing and shoving and ignoring all the rules.”