Mine spokesman draws ire

As he keeps watch outside the Utah coal mine where six of his employees have been trapped since Monday, Robert Murray angrily fends off suggestions that it was his company’s mining technique, and not an earthquake, that caused the collapse 1,500 feet below ground.

Murray’s confrontational stand outside the Crandall Canyon mine is just one more battle in a war he has been waging in defense of an industry he believes is unjustly vilified. In the past year, Murray has emerged as one of coal’s most ardent defenders against charges that it is driving global warming, making the case on Capitol Hill and in interviews that restricting coal would decimate the U.S. economy.

“I know what’s going to happen to families … and I cannot sit back and let it happen,” Murray said in a lengthy interview with the Washington Post earlier this summer. “I’m an American first, and I resent extremely that what you are doing is destroying the American economy and causing the deterioration of the American way of life.”

Wednesday, he told reporters at the scene that rescuers were seeking to drill a hole within two days to provide the miners with air, water, “everything they need, even a toothbrush and comb.” He repeated that it could be at least a week until the miners could be brought out, after rescuers were forced to give up the fastest route, an old mine shaft, because of falling rock.

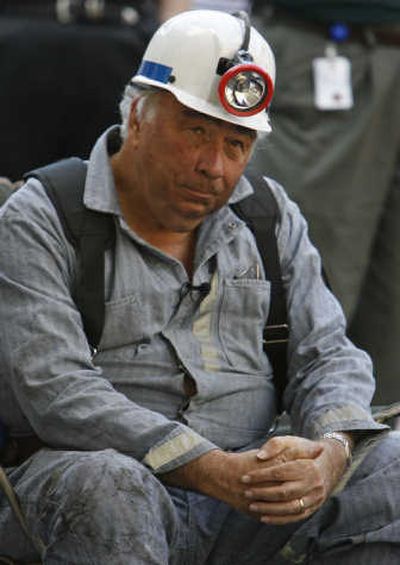

The stocky 67-year-old mine operator’s style in handling the disaster fallout is getting as much notice as the progress of the rescue. In the televised press conferences, he has struck a feisty, unpredictable tone, swinging between tart rebuttals of reporters’ questions – he singled out some for “particularly bad reporting” – and pledges of solidarity with the trapped miners. “I will not leave this mine until those men are rescued, dead or alive,” he said.

On Tuesday, he used the spotlight to deliver a general paean to coal, with harsh warnings of a sort that many economists have challenged: “Without coal to manufacture our electricity, our products will not compete in the global marketplace against foreign countries because our manufacturers depend on coal for low-cost electricity, and people on fixed incomes will not be able to pay for their electric bills,” he said. “Every one of these global warming bills that has been introduced in Congress today will eliminate the coal industry and increase your electric rates four- to fivefold.”

Murray’s unconventional handling of the press conferences has drawn criticism from Reps. George Miller and Lynn Woolsey, both California Democrats and chairs of House committees that oversee labor and workforce issues. They have urged the Department of Labor to take over the spokesman role from Murray, saying his statements do “not meet (the) standard” expected at such emergencies.

Despite the lawmakers’ criticisms, Murray was back at the microphones in his characteristic sweater vest Wednesday, dismissing the notion that the mine collapse was caused by a method known as “retreat” mining. The technique involves miners working their way out of a mostly exhausted mine by excavating coal in the rock pillars that support the roof of the mine. As the coal is extracted, the pillars and the mine roofs eventually fall down.

The mine had a permit to use this approach, and Robert Friend, deputy assistant secretary of the Mine Safety and Health Administration, said in an interview Wednesday night that while the cause of the collapse is still undetermined, it is clear that “there was retreat mining where these miners are.” Of Murray’s denials that retreat mining played a role, Friend said, “I can’t speculate as to what he meant.”

Seismologists have disputed Murray’s contention that the collapse was caused by an earthquake. An analysis of seismic waves that occurred in the area around the time the mine collapsed are consistent with what would be seen from a mine collapse, not an earthquake, said Harley Benz, who heads the National Earthquake Information Center in Golden, Colo. Any subsequent seismic activity that has been detected may have been related to energy being released in the aftermath of the collapse, he said.

Murray Energy, which co-owns the Crandall Canyon mine with Intermountain Power Agency, is based in Cleveland and operates 11 mines in Ohio, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Utah producing 32 million tons of coal annually, with $468 million in sales and 3,000 employees. It is the country’s largest independent, family-owned coal producer.

Murray has been at the company’s helm since he founded it 20 years ago, but he likes to remind his audiences that he is no boardroom suit. He comes from three generations of coal miners in southeastern Ohio, his father was paralyzed in a mining accident, and he himself has been injured below ground. (He pulled back his shirt to show reporters one scar this week.) After considering medical school, he won an engineering scholarship at Ohio State University and spent the next three decades at North American Coal. He rose to chief executive but left in 1987 after, he says, clashing with the board over its plan to slash pensions. He then took out a mortgage on his house to start his own company.

For all his clashes with the United Mine Workers, union officials say Murray’s mines are in general on par with others when it comes to safety issues. In the interview, he said that he took safety seriously, partly because of his own work as a miner. “There’s been nothing but safety for me,” he said. “I take it to bed with me every night.”

He has sought to strike a similar tone outside the Utah mine, though his hopes for finding the miners were mixed with a world-weary fatalism. “The Lord has already decided whether they’re alive or dead,” he said. “But it’s up to Bob Murray and my management to get access to them as quickly as we can.”

He defended his performance in the press conferences, saying his main role was to oversee the rescue and comfort families. “I am a coal miner,” he said. “I have responsibility for this rescue. I am not a professional in talking to you or Americans. I am a professional in talking to miners in distress.”