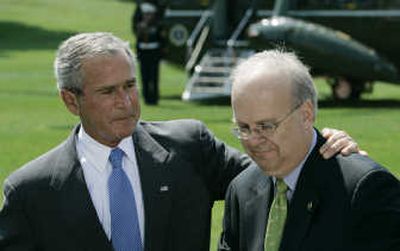

In resignation, Rove still roils

WASHINGTON – President Bush once nicknamed him “the architect,” heaping gratitude on his chief strategist for helping engineer two presidential victories and two cycles of congressional triumphs.

But after Karl Rove resigned Monday, a question lingers over his legacy: What, exactly, did the architect build?

His advocates credit him with devising a winning strategy twice in a row for a presidential candidate who seemed to start out with myriad weaknesses. His detractors blame Rove for a style of politics that deepened divisions in the country, even after the unifying attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Both sides attributed outsize qualities to him, and he enjoyed mythic status for much of the Bush presidency.

But few people – not even his Republican allies – believe Rove succeeded in what he set as his ultimate goal: creating a long-lasting Republican majority in the country that could reverse the course set 70 years ago by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“He had visions of building a long-term coalition like the New Deal coalition for the Democrats,” said Rep. Thomas M. Davis III, R-Va., who spent two years as head of the National Republican Congressional Committee, which works to elect Republicans to the House. “The party right now is not moving forward. It’s moving backward. The branding for the party is at a generational low.” Davis said that is largely due to the war in Iraq.

Rove’s admirers and friends say he deserves credit for two undeniable accomplishments: building the Republican Party in Texas in the 1990s and securing Republican control at the national level, at least for a time, at the turn of the 21st century.

“He put together a strategy that defied all expectations and all conventional wisdom, and established a Republican majority in the presidency and then the two houses of Congress for the first time since 1936,” said Mark McKinnon, who worked with Rove on both Bush elections and now advises Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

Once dubbed “boy genius” – another nickname Bush gave him and the title of a 2003 biography – for his mastery of the political landscape and his seeming ability to grasp the electoral zeitgeist, Rove never clung to one political theory over time but shifted as events required. Perhaps his greatest consistency was his likeness to Lee Atwater, the ruthless and effective South Carolina operative who made Rove a protege.

It was the hardball tactics he learned from Atwater as much as his strategic vision that made his reputation and provoked an endless search by Democratic and Republican opponents for what the New Yorker magazine once called “The Mark of Rove” – that he was behind any given campaign calamity.

To this day, McCain loyalists blame Rove for mounting a whispering campaign against the senator during the 2000 Republican primary in South Carolina, while allies of former Democratic Sen. Max Cleland of Georgia accuse Rove of engineering the tactics against the wounded Vietnam veteran that cost him his 2004 re-election bid.

Rove, a self-made intellectual who never graduated from college, came to power convinced that Republicans could remake government in a fashion that would secure conservative prevalence for years to come. The realignment Rove envisioned would have returned ownership to individuals (in the form of personal retirement savings accounts and health care plans) and in so doing lure new types of voters, in particular Hispanics and African Americans, to the party.

But after easing Bush into a “compassionate conservative” persona that appealed to the Texas electorate while he was governor and to the political center in the 2000 presidential election, Rove shifted to focus on turning out the conservative base – a strategy that worked for Republicans for a short time but eventually cost it the chance to expand.

However his rivals viewed it, Rove’s strategies worked, both for Bush and for the Republican Congress – at least through 2004. House Republicans gained six seats in 2002, and Senate Republicans gained two seats that same year. In 2004, House Republicans gained four seats; Senate Republicans gained another four.

But by 2006, the coalition Rove cobbled together for Bush had fallen apart. Political independents broke heavily for Democratic congressional candidates in the midterms, fueling the Democratic takeover of Congress. That shift undermined the theory Rove had been credited with turning into doctrine: that driving up your political base is more important than appealing to independents or the political center.

In truth, Rove did not see it as an either/or choice. He took a two-tiered approach: encouraging Republicans to vote for the president, as well as chipping away at more Democratic blocs of voters such as Hispanics and Catholic women.

“The lesson we took out of 2000 was that if we did things in 2004 the same as we did in 2000, we would lose,” said Ken Mehlman, who was the Bush campaign manager in 2004 and then served as chairman of the Republican National Committee. “And so we spent four years experimenting on ways to expand support among the base and also persuade swing voters and Democratic-leaning voters to be Republicans.”

It was this quality, which Democratic strategist Carter Eskew described as Rove’s ability to “slice and dice the electorate,” that seemed to deliver Bush’s victory in 2004. While Sen. John F. Kerry, D-Mass., won 8 million more votes than former Vice President Al Gore did four years earlier, Bush outdid himself by winning 12 million more votes in 2004 than he had in 2000.

“There aren’t many people who have both vision and practical knowledge,” said Eskew, who advised Gore.

Rove sought to reach far beyond Washington. He encouraged Republicans in Texas to pursue redistricting to add Republican seats to Congress. He called candidates at the state level, keeping tabs on minor political quarrels and intervening in primaries.

From the White House, Rove traveled constantly to help nudge a local race or a state party in the direction he wanted. Such efforts were once welcomed, but as the president’s popularity waned, Rove’s allure faded among local candidates and operatives.

“His problem is that he’s inexorably linked to Bush,” said former RNC chairman Rich Bond. “And the degree to which Bush is viewed favorably by history, so, too, will it Karl Rove. The degree to which history judges George Bush harshly, so, too, will it judge Karl Rove.”