Hope for miners dwindles further

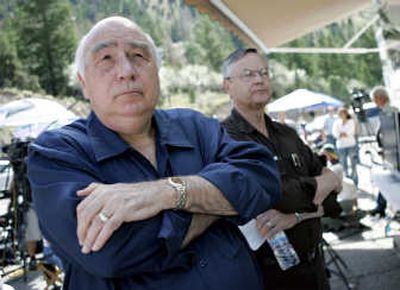

Since the moment last week that a Utah mine collapsed with six men trapped inside, mine co-owner Robert Murray has stuck to a simple message. “The miners could still be alive,” he says over and over again. “There are many, many reasons to have hope.”

But on Tuesday, for the first time, Murray did not speak of hope at his daily news briefing about the rescue mission. It was a quiet acknowledgement that the likelihood of finding the men alive is decreasing.

Jeff Goodell, who wrote the books “Big Coal” and “Our Story,” about the 2002 Quecreek Mine rescue in Pennsylvania, said: “I’ve talked to the mining engineers (in Utah) about this, and a lot of people out there think they’re dead. I don’t think they could have survived this long.”

Gerry Finfinger, senior scientist for the mining program at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, said, “Certainly we’re all concerned, because it’s eight days now.”

The latest prediction is that it will take five to seven more days to reach the trapped men by tunneling underground. Meanwhile, rescuers are drilling holes into cavities where they think the men may have gone.

“The big issue right now for these guys is air,” Goodell said. “There’s potable water down there and they can certainly go without food this long. The issue is, were they hurt in the initial collapse, and do they have enough air?”

The news so far has not been promising. Two air samples showed that the oxygen content where the men were working was 7 percent, not enough to keep them alive.

With a camera lowered 1,800-feet through the earth, rescue workers saw mining tools, a worker’s bag and a conveyor belt, but no miners.

Stephen Dmytriw, a registered civil engineer at the Colorado School of Mines, said that when he saw the video he thought the worst. “You don’t leave your tool bag hanging around,” he said.

Miners are trained to search for exits, and if those are blocked – as they are at Crandall Canyon – then they look for a space with oxygen, Dmytriw said.

If the miners found such a place, they would quickly build a barricade from concrete blocks. “Once you go in, you never take the barricade down,” Dmytriw said. “They would wait for the rescuers.”