Better care for vets urged

TACOMA – Injured during a raid to capture an Iraqi insurgent in 2004, Washington National Guardsman Daniel Purcell returned home to discover that getting surgery meant a years-long tussle with a medical “bureaucratic asylum.”

“Unlike Iraq, where the mission and the enemy were clear, I was now faced with a new enemy called budget cuts, rationed resources and misplaced priorities,” Purcell, a Spokane native, testified at a U.S. Senate hearing in Tacoma Friday. “Every day is a new day and another exercise in futility.”

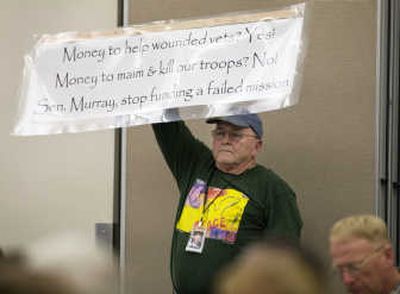

The hearing, called by Sen. Patty Murray, comes on the heels of what she called a “heartbreaking” new Department of Defense report indicating that Army suicides are at a 26-year high. Murray on Friday said the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration need to do a better job of treating both physical and mental wounds.

“It is clear that the VA is still not on a wartime footing to deal with this problem,” Murray said. “Caring for our troops when they return home is a cost of war.”

Military and medical officials defended the system, which they said is improving quickly.

“I have to tell you that leaders are taking this seriously,” said Brig. Gen. Sheila Baxter, commander of the Madigan Army Medical Center at Fort Lewis. Six months ago, she said, a soldier showed up at his engineering unit and said that the night before he’d held a gun to his wife’s head.

“We were able to get him in to speak to a psychiatrist immediately,” Baxter said.

More than 717,000 men and women have left the military since 2002, according to VA consultant Antonette Zeiss. Of those, 35 percent have sought VA medical care, including a growing number seeking treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

“War is a different animal,” said Purcell, who said he also wrestled with post-deployment depression and anxiety. “We went to war and were changed.”

National Guard Sgt. Stephen Franklin said he was angry, chronically uneasy and unable to sleep after returning from a year-long Iraq deployment 18 months ago. Only after many months, he said, has treatment started to work.

Fellow Guardsman Brandon Jones spoke of a friend, unable to cope with the stresses of combat, who went home alone one day and fatally shot himself in the head.

“Where were those assigned to ensure his well-being?” Jones asked.

Army Col. Greg Gahm, chief of the psychology department at Madigan, was one of those who worked on the national suicide report. Among its findings: There were 99 confirmed suicides among active-duty troops last year. Over 26 years of tracking, the number of troops killing themselves ranged from a 2001 low of 9.1 per 100,000 to last year’s 17.3. The most common locale for suicide: Iraq.

Murray asked Gahm how many suicide attempts there have been. He said it’s impossible to say, since some attempts are never documented. But he estimated “as many as seven times the number of completed suicides.”

“That was astounding to me,” Murray said after the meeting. “That should be the biggest alarm bell to all of us that we are bringing men and women home from this conflict that aren’t getting the help and care and support that they need.”

Among recent veterans, Zeiss said, mental health problems are now the second-most common health concern.

To meet that growing demand, she said, VA officials “have improved capacity, access and hired over 3,000 new mental health professionals.”

Vietnam veteran Ron Fry called Murray a “hero” for pushing to keep VA facilities open. Fry, who recounted leafing through the family photos and diary of a dead Vietnamese soldier, said the horror of war doesn’t fade. One of his last acts in Vietnam, he said, was scrambling into a crowded helicopter and having to sit on a stack of body-bagged dead GIs.

“You can smell the gunpowder. You can feel the explosions. You can hear the screams and cries,” he said. “They’re here right now with us.”

Maj. Gen. Timothy Lowenberg, adjutant general of the Washington National Guard, said that guardsmen face unique difficulties. When active-duty troops return from combat, for example, they typically get a month of half-day work so they can decompress and reintegrate with family and friends around the base. Guard members, on the other hand, typically return to civilian work within 10 days and often have no one nearby with shared experiences to turn to. They’re often far from military health care and reluctant to seek help for fear of losing their civilian jobs.

As a result, Lowenberg said, small stress or brain-injury disorders can “blossom into intractable patterns of unemployment, substance abuse, family separation and divorce.”

Problems like traumatic brain injury and mental health problems are especially hard to quantify, Murray said, partly because troops are reluctant to speak up.

“I’ve had soldiers say to me, ‘I would have been better off to lose a leg than to have post-traumatic stress syndrome, because not only would I have gotten services faster, but my community would have recognized my sacrifice.’ “