Surgery helps obese live longer

Obese people are significantly less likely to die if they undergo stomach surgery to lose weight, according to two large new studies that offer the first convincing evidence that the health gains of losing weight translate into living longer.

The research, involving some 20,000 obese people in the United States and Sweden, found those who underwent surgery had about a 35 percent lower risk of dying over the next seven to 10 years compared with those who went without the operations.

Previous studies have shown that losing weight cuts the risk of diabetes, heart disease, cancer and other major ailments and suggested that might lead to an increase in longevity. But the new studies offer the strongest evidence to date to answer one of the most important and contentious questions about one of the nation’s biggest health problems: Does weight loss result in not only healthier lives, but also longer ones?

“The question as to whether intentional weight loss improves life span has been answered,” wrote George Bray of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La., in a commentary accompanying the studies in today’s issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. “The answer appears to be a resounding yes.”

The proportion of Americans who are overweight has been rising steadily, and two-thirds are now considered overweight, including about a third who are obese. The trend increases the risk of a host of health problems, but skeptics have questioned whether being fat necessarily shortens life, and whether intentionally losing weight extends it.

“This is very exciting,” said David Flum of the University of Washington. “Although we’ve known for years that weight loss can reduce medical conditions associated with obesity, the link between a reduction in these conditions and an increase in longevity has been elusive. This is huge.”

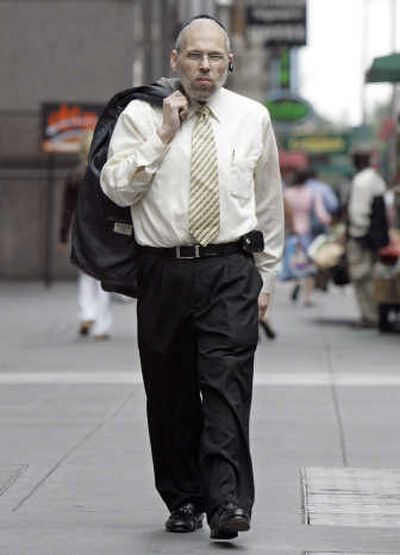

Herb Olitsky, a 53-year-old business owner from New York City, credits his improved lifestyle to gastric bypass.

A diabetic, Olitsky was given months to live after developing a life-threatening bacterial infection near his heart muscles.

Olitsky, who stands 5 feet 8 inches, underwent stomach-stapling surgery in 1999 and went from 520 pounds to his current weight of 160. He no longer struggles to walk a quarter block and has managed to control his blood pressure and heart rate.

“I knew I had to get it and that’s what’s kept me alive,” Olitsky said. “I’m healthier now than I’ve ever been.”

The obese people who underwent surgery in one of the studies lost 14 percent to 25 percent of their body weight. The studies did not examine whether losing only moderate amounts of weight, or losing weight by dieting, would also lengthen life spans, but several experts said they believed it would.

“This makes it clear that if you can get people to lose weight they are going to live longer,” said Louis Aronne of the Weill Medical College of Cornell University. “That is what people in the field have been saying for years. Now we have proof.”

Skeptics, however, remained unconvinced. They argued that the longevity benefit in the studies was relatively small, especially when weighed against the risks of stomach surgery.

“I would hate to see these studies being used to justify the argument that we should be doing weight-loss surgery to save lives,” said Paul Campos of the University of Colorado, author of “The Obesity Myth.”

“The claim that we have to give people weight-loss surgery to keep them from dying imminently is greatly exaggerated. At best it’s a very, very modest effect.”

In fact, the data could be interpreted as showing that obese people live fairly well without surgery, others said. Mortality for those who were not treated remained very low, they said.

“Until today, we have had little information on how well extremely obese people do without treatment,” wrote Paul Ernsberger of Case Western Reserve School of Medicine in an e-mail. “Even though the group ranged up to 60 years of age, 96 percent of them survived for 10 years. Nearly 88 percent survived for 16 years. These are far better odds than doctors are predicting for their fat patients.”

But others said the studies demonstrated a clear advantage from surgery. In the first study, Ted Adams of the University of Utah and colleagues looked back at 7,925 severely obese people who had undergone stomach surgery and 7,925 similar obese people who had not. After an average of about seven years, those who had stomach surgery were about 40 percent less likely to have died, the researchers found. Those undergoing surgery were 92 percent less likely to die from diabetes, 60 percent less likely to die from cancer, and 56 percent less likely to succumb to heart disease.

In the second study, which several researchers said was even more convincing, Lars Sjostrom of the Goteborg University in Sweden and colleagues followed 2,010 obese patients who underwent stomach surgery and a similar group of 2,037 patients who had not had the operation, also known as bariatric surgery. Over the next 11 years on average, those who had surgery were about 30 percent less likely to die from any cause.

“This study for the first time offers strong evidence that intentional weight loss, or at least bariatric surgery, is associated with decreased morality,” Sjostrom said.

Several other experts agreed that the studies provide strong support for the surgery for severely obese patients but questioned whether the procedures were being done too frequently on less overweight patients who might be able to lose weight in other ways.

“I would argue that making fundamental changes in our lifestyles would be a healthier and in the long run more efficient goal,” said David Zingmond of UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.