Taking the long view

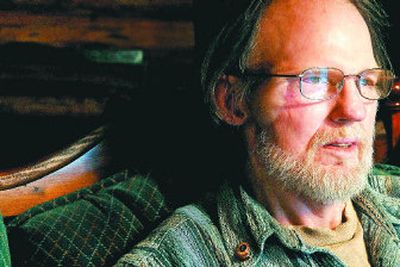

For a dozen years, Terry Stidman has fought to keep cancer from claiming his right eye.

In December, doctors told him he’s losing the battle.

“My thought was, it’s just the cancer trying to take more of me away,” said the 52-year-old Spirit Lake man.

But Stidman figures the terminal illness can’t steal something that’s given freely.

So on Tuesday, he’s scheduled to allow surgeons in Seattle to cut out his diseased eye for use in scientific research.

The operation will disfigure Stidman, leaving only a flap of transplanted skin where his eye and cheek now sit.

He’ll lose the limited sight he now has in that eye, but he’ll also become a rare living eye donor whose tissue could hold the key to promising gene research, experts said Friday.

“It may mean they can shut down macular degeneration in elderly people,” explained Stidman, who has spent more than a decade advocating for vision projects as a member and officer in regional Lions Clubs.

Within 10 hours of the scheduled 7:30 a.m. operation, Stidman’s eye must be flown from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center to arrive at the John A. Moran Center in Salt Lake City.

There, a team representing Dr. Kang Zhang, a genetic researcher and clinician, will be waiting to receive the delicate material. It will be processed immediately for use in a project aimed at investigating a gene responsible for age-related vision loss.

With Stidman’s help, Zhang and other researchers will continue to develop a blood test that may identify those at risk for the leading cause of blindness after age 55, affecting more than 10 million people in the United States each year.

“I don’t know this gentleman, but he’s doing a major service for people with that condition,” Bob Rigney, chief executive officer of the American Association of Tissue Banks, said Friday.

Stidman learned he’d have to lose his eye late last year, when doctors found that the rare adenoidal cystic cancer first diagnosed in 1994 had spread even further than his cheekbone.

“The cancer has invaded the orbital cavity,” said Dr. Eduardo Mendez, the Seattle head and neck surgeon who will perform the operation.

That was a blow to Stidman, who already understood he wasn’t going to cure the illness that was supposed to have killed him by last May.

“Every day’s a freebie,” says Stidman, who jokes that he beat the terminal “deadline” doctors gave him four years ago.

But it did explain the throbbing pain that plagues Stidman day and night.

Only playing music – bluegrass and folk, heavy on the guitar – and 300 milligrams of morphine a day can make a dent in the haze, he said.

“I used to sing good,” he said, cradling his 12-string. “It bothers me that I’m losing all that.”

And it accounted for the change in the discolored bulge that distorts the right side of his face, where previous surgeries tried to correct the problem – and failed.

And it meant that by Wednesday, he’ll have only soft tissue where his hazel-blue eye now blinks. The extent of Stidman’s disease means doctors can’t reconstruct his face, Mendez said.

“I am worried as far as the cosmetic goes,” he said. “I’m not vain, it’s not that. I already get a lot of looks from kids. I’d hate to scare them.”

Stidman figured if he had to lose his eye, he wanted it to go for a good cause. If pain relief is part of the equation, that’s a boost.

“If they couldn’t use it for research, I wasn’t going to go through with the surgery,” he said. “I’m not going to give my eye up for the garbage.”

Stidman, a former district governor with the Lions Club, contacted the Northwest Lions Sight and Hearing Foundation, which operates Sightlife, the Seattle-based eye bank.

“We wanted a project that would be worthy of such a staunch Lion as Terry, so we asked the Utah Lions Eye Bank to help us find one,” said Bob Scheffels, a spokesman.

When Stidman heard about Zhang’s work, he immediately agreed. “This is an honor to do this,” he said.

Stidman’s donation will be processed like the more than 2,600 corneas donated for transplants and research last year through the Northwest eye bank.

Stidman’s donation is rare, said Rusty Kelly, vice president of the Eye Bank Association of America. Although many patients lose their eyes to cancer and other illnesses, and the organs are removed, analyzed and preserved, they’re not targeted specifically for research.

“I have only heard of this a few times in eight years,” Kelly said.

Obtaining tissue so soon is a huge boon to researchers.

Virtually all eye tissue in the United States is supplied by dead donors; even living people who want to donate corneas to loved ones, for instance, are prohibited.

Making sure his donation means something is important to Stidman, who said he’s always lived by the philosophy attributed to Colin Powell: “Giving back requires a certain amount of giving up.”

A former Marine and diamond driller whose last job was driving a Spokane delivery truck, Stidman has volunteered in community projects for nearly all of the 22 years he’s lived in Spirit Lake.

“There’s nothing better than going to bed and knowing you’ve helped people,” he said.

He’s worried about what life will be like after next week. He wonders what his two toddler grandchildren will make of their grandfather’s new face.

“It’s going to be shocking,” he said softly.

But Stidman said he hopes he’s back home soon, recovered enough to pick up a guitar and perform. He offers to play a song for a visitor now, just for the joy of it.

It’s a Simon & Garfunkel tune, one of his favorites, crooned in a high, sweet tenor:

The mirror on my wall

Casts an image dark and small

But I’m not sure at all it’s my reflection.

I am blinded by the light

Of God and truth and right

And I wander in the night without direction.

So I’ll continue to continue to pretend

My life will never en/

And flowers never bend

With the rainfall.