Novelist in clubhouse

PEORIA, Ariz. – Jarrod Washburn is reading a hunting magazine. Other Mariners are seated at a table in the middle of the clubhouse, working a crossword puzzle a staffer has photocopied from the morning paper.

Rapper Will Smith is loudly reciting the wonders of the half-naked women and nightclubs of Miami, through the clubhouse’s stereo system.

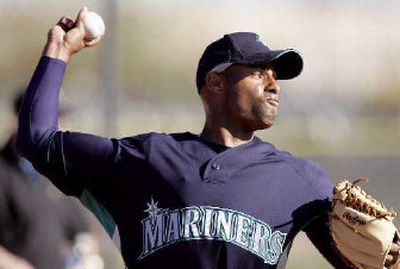

And Miguel Batista is seated alone and silent on a stool at his locker.

He’s reading inside a three-ring binder covered with the title, “Human Cloning,” researching for his second novel. The subtitle: “Jesus Cloning.” Readings from Leo Tolstoy and the Bible are also handy.

Not quite the standard literary fare of a baseball clubhouse.

“Whenever they see me and what I am reading, they always shake their head and say, ‘Man …,’ ” Batista said Friday.

He squeezed his dark eyes closed. He turned his head from side to side to imitate how his teammates have reacted to him for years, from Seattle to Arizona to Toronto to Montreal.

“Either they are – or I am – in the wrong place,” he said, laughing.

“For them, it is shocking that a guy is actually interested in something other than the world of baseball.”

Batista, 36, is one of three new Mariners starters, an 11-game winner with the Arizona Diamondbacks last season who is 68-79 for seven teams since 1992. While every other Seattle pitcher easily quotes his latest radar gun reading, Batista is easily quoting “The Da Vinci Code.” Plus, Al Capone. Ted Bundy. Wayne Williams. Stephen King.

Batista is voracious reader because he is a writer – the first Latin American professional player to publish a book of poetry.

This month, he is researching his second novel, about scientists and specialists who have been called to Washington, D.C., and to the United Nations to repair a secret government project. The project has gone horribly wrong and is threatening to “bring Armageddon to the world behind the scenes,” Batista said.

His first novel was published last year. “The Avenger of Blood” details a 14-year-old serial killer – and the American legal system’s struggle in defining the concept of temporary insanity.

He wrote the book in Spanish, the language in which it was first published 13 months ago. The third edition was just published in the Dominican’s native language and the English version debuted last September.

Batista’s goal in writing it?

“It was to find out, what exactly is an ‘insane’ person? And, how can we quantify a criminal mind?” he said.

Batista said he learned how American law may actually make it “better” for a person to kill 200 people than just one, because the mass murderer can be classified as insane and not necessarily sentenced to death.

“I had a defense lawyer tell me the temporary insanity definition changes every day,” he said. “I mean I hear voices every day. My ex-wife, I hear her every day. Does that make me crazy?”

Like Batista himself, there’s so much more to the book than the cover.

The book’s original title, in Spanish, translates to “Through the Eyes of the Law.” But when Trafford Publishing prepared to release the book for an English audience, the company changed the title to make it more horrific, less academic-sounding and thus presumably more marketable.

Batista went to extraordinary lengths to understand American law for someone with a day job as a $25 million pitcher. He spent 5 1/2 years – while playing for Montreal, Kansas City, Arizona, Toronto and Arizona again – researching and writing on road trips, before and after games.

“Between batting practices, you have 45 minutes (before games),” said the veteran of parts of 12 major league seasons. “If you aren’t pitching that day or the next day, you don’t have much to do. You can take that time to relax, or whatever.

“I would take some of that time to write – and then take it home to type.”

While his teammates partied late, slept until maybe noon then went back to the ballpark to eat and watch “Dumb and Dumber” on the clubhouse couch, Batista visited an Arizona prison to probe real criminal minds. He went to a psychiatric hospital. He interviewed judges, lawyers, policemen and detectives.

During his research and writing, his teammates thought he was a freak of clubhouse nature – which, of course, he is. The Blue Jays, for whom he went 15-21 in 2004 and ‘05, nicknamed him “The Riddler.” They could never understand what it was he was talking about.

“A lot of us are protected under the bubble of the baseball life,” Batista said of an industry where the minimum major league salary is $380,000 and a sub-.500 career pitcher like he can earn an average salary of more than $8 million.

“A lot of people don’t believe there is an outside world, another life. Baseball has been such a shield for some people that it doesn’t let them see or feel the actual chaos in the world.

“Sadness and catastrophe happen … we are not as blessed as we thought we were.”

Batista’s writing began formally at age 13, when he began expressing himself with a pen – and found out they called it poetry.

Growing up in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, he was forced to watch novellas on the family television because his mother never changed the channel from them. Soon, he had favorites. Then he challenged himself to write one. He did, at age 16.

Batista said he will continue writing long after his playing days end – which, given his age, may be when his Seattle contract expires in 2009.

“Writing is like meditation. It’s something you don’t walk away from,” Batista said. “The awakening of the mind is the course of being alive. When you are awake, you never go back to sleep.

“You just keep on questioning, keep on asking.”