Diocese files settlement

Spokane Catholics will be asked to participate in one of the largest – and most controversial – fundraisers ever attempted in their diocese’s history: $10 million to pay lawyers and victims of priest sexual abuse.

Unlike past campaigns, they won’t have a choice: Failure to raise the money could mean the sale of their churches and schools.

After more than two years of legal wrangling and mounting attorney fees, a $48 million settlement to end the Roman Catholic Diocese of Spokane bankruptcy was filed Thursday.

The settlement is part of a bankruptcy plan approved by all parties in the case, including the diocese, parish leaders and victims. It not only provides a fair resolution to more than 100 victims of clergy sexual abuse, according to a court-appointed federal mediator, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Gregg Zive of Nevada, it also allows the diocese to continue its Eastern Washington ministry.

The plan needs to be approved by the Spokane judge overseeing the case.

“It has been a complex and often emotional process, but one that was essential to avoid protracted, debilitating, risky and expensive legal disputes,” Zive said.

The $48 million includes about $20 million from insurers. Bishop William Skylstad’s diocese will be responsible for raising about $18 million, which will include money from the sale of property such as the bishop’s home and the Catholic Pastoral Center, called the chancery. Money also will come from other Catholic entities, including Catholic Cemeteries.

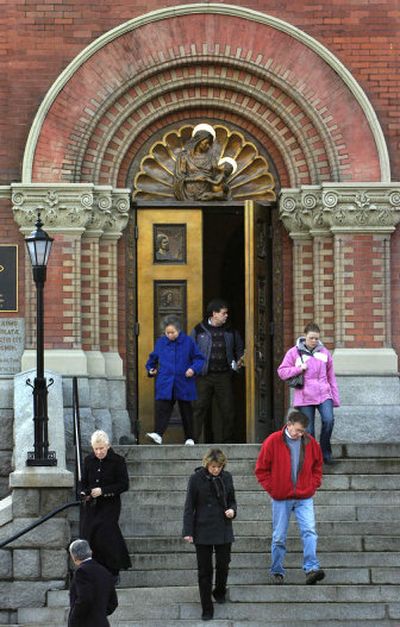

Beyond the $10 million parish commitment, four of the largest parishes in Spokane and the Immaculate Heart Retreat Center will be used as collateral for a $5 million note from the bishop. The parishes that will secure the bishop’s financial promise are: Our Lady of Lourdes downtown; Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in northwest Spokane; St. Augustine on the South Hill; and St. Mary in Spokane Valley.

If the bishop defaults on his financial obligation, the four parishes would be subject to foreclosure before lenders turned to the retreat center. Furthermore, according to court documents, Our Lady of Lourdes is backing a separate, third note for $1 million as part of the agreement.

“This needs to be settled, and we need to move on and get on with our lives,” said Michael McGuire, a parishioner at Our Lady of Lourdes. “I have confidence in Bishop Skylstad. He’s guided us through some difficult times – God, the bishop and the Holy Spirit.”

The sex abuse scandal, coupled with the Chapter 11 bankruptcy, has dampened the spirits of many parishioners. Like McGuire, Catholics throughout the diocese were relieved to hear that an end could be in sight.

“It’s been heavy on my heart,” said Joan Nolan of St. Mary. “I have hoped and prayed for a resolution – one that works not only for the parishioners and the priests, but also for the abused.”

The settlement was met with mixed reactions from abuse victims. While some embraced the plan, others only grudgingly agreed. They described the settlement as little more than a thinly disguised ultimatum that neither pays them what they think they deserve nor holds the Catholic hierarchy accountable for covering up decades of child molestation.

“We’re not thrilled by this. Not at all, but what are we to do?” said Michael Ross, who filed a sex abuse claim and supports the settlement. “Listen, $48 million is a lot of money to keep Bishop Skylstad off the witness stand. That’s the crux of the problem. That’s why parishioners of this diocese are going to be paying enormous amounts of money to lawyers and victims.”

Steve Denny, another victim, sounded hopeful. “This plan provides everyone with an opportunity to heal,” he said. “We’re very optimistic and happy to see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Bankruptcy lawyers and other professionals have been paid $2.6 million since the case was filed Dec. 6, 2004. They are owed $5.56 million more in accrued fees as of Nov. 30, 2006. The $8.2 million in fees – when combined with the contingency payments due lawyers representing victims – likely means that more than half of the $48 million settlement will be paid to attorneys.

About 36 victims, including many of the smaller claims, have already settled with the diocese. The amounts range from $4,000 to $300,000.

Most claims, however, have yet to be settled, including those considered so serious by the diocese that the organization sought bankruptcy protection rather than go to trial.

Not all victims may choose to settle. Some remain insistent on having their day in court to face the bishop and air their case before a jury or judge.

The combination of church and state, money, politics and childhood sexual abuse claims, along with state and federal legal considerations, made this bankruptcy case especially toxic and difficult to resolve. Anger and mistrust, even between the bishop and parishioners, resulted in numerous setbacks.

“This is the toughest … mediation I have ever done,” Zive said from his chambers in Reno, Nev. “Nothing else comes close.”

Zive, who issued a gag order among those involved in the mediation, described the settlement as a product of compromise and hope.

The settlement is wrapped into a 113-page court document called a bankruptcy plan of reorganization. It is a blueprint outlining how the diocese will settle its debts – in this case, claims – and emerge from court protection intact and able to continue operations.

Those involved in drafting the plan are not allowed to solicit support for it. Instead, they will file a prospectus, or disclosure statement, highlighting how it all works and why they feel it’s in the best interests of all involved.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Patricia Williams, who is overseeing the case from Spokane, must hold hearings on the plan to consider objections, and ultimately approve it.

The settlement is unlike the proposal that failed last spring. Williams rejected as unfair that $45.7 million deal between the diocese and a group of 75 victims, after parishioners recoiled at the price tag and the fact that it didn’t include all victims.

In addition to the money that will be allocated to victims, the current plan requires Skylstad to publicly support the elimination of all criminal statutes of limitation for child sex abuse.

Other so-called nonmonetary requirements included in the plan require the bishop to visit every parish where children have been sexually abused and read a statement from the pulpit identifying pedophile clergy that served at the churches. Also, the diocese must post the names of all priests ever credibly accused of pedophilia and allow victims to speak publicly in the parish where they were abused.

The final paragraphs of the plan call for the diocese to quit using the term “alleged” when referring to victims of clergy sex abuse and require the bishop to send letters of apology to victims and their families, if requested.

Zive called these obligations “absolutely essential to arriving at a consensual plan.”

The plan does not require the removal of Skylstad from his post. In many corporate bankruptcies, chief executives are often fired or resign.