Towering presence

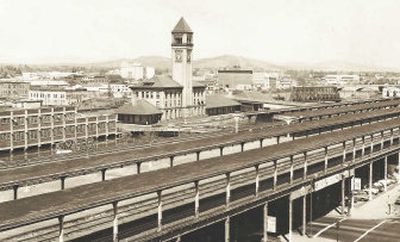

Not many people these days can tell you the exact site of one of Spokane’s grandest edifices, the Great Northern Railroad Depot.

Oh. Wait. Actually, just about everybody can.

The tallest, most imposing part of the Great Northern Depot still exists, right smack on its original spot on Havermale Island. It’s known as the Clocktower at Riverfront Park, the only remnant of a once-glorious building. The depot surrounding the Clocktower was torn down in 1973 to make way for Expo ‘74 and Riverfront Park.

It was an ignominious end to what was one of the most impressive buildings in the city when it was finished in 1902. The Spokesman-Review enthused at the time that it was “the finest (depot) west of Chicago, not excluding the Twin Cities.”

James J. Hill’s Great Northern locomotives had been steaming into the city since 1892, yet for almost 10 years the Great Northern didn’t have a depot of its own. It had to share space at another railway’s station.

Clearly, this would not do. So in 1901, the Great Northern began work on a building that would cost $200,000 (the equivalent of more than $4 million today). In May 1902, the railroad dedicated a veritable railroad temple, three stories tall, with a 155-foot tower rising majestically from the middle and serving as a giant landmark and public wristwatch. The Seth Thomas clock had four dials, each nine feet in diameter. The entire apparatus weighed 7,000 pounds.

The bottom floor of the depot served as a spacious public waiting area. The upper stories were dedicated to office space. The newspaper called it the “best-lighted building in the city,” with 100 electric arc lights, each lighting fixture decorated with the GN logo.

The entire building was designed, originally, to present a grand aspect toward downtown.

“It faced the center of the city across a reflecting pool of the still water of the south channel,” wrote Robert B. Hyslop in his invaluable book, “Spokane’s Building Blocks.”

In front was an impressive esplanade of masonry river-wall. In its glory days, the esplanade was “graced with flower boxes of geraniums,” wrote Hyslop.

Alas, the grand view lasted only until 1914, with the construction of the Union Pacific Depot, on what is now Spokane Falls Boulevard. This new rival building effectively blocked the view of the depot from downtown – possibly on purpose – and marred the entire “reflecting pool” concept. Yet nothing could block the view of that tower.

Thousands of railroad travelers were familiar with the interior as well. Former U.S. House Speaker House Tom Foley remembered the depot’s “high ceilings and oak benches,” when interviewed by historian J. William T. Youngs for his excellent history of Expo ‘74, “The Fair and the Falls.” Footsteps clattered on the marble floors, and the cries of “all aboard” echoed off the rafters.

The big Clocktower sported both the initials “GN” and “SP&S” (the Spokane, Portland and Seattle line, which also operated out of the depot).

Yet as the midpoint of the century passed, railroad passenger traffic began to decline and the railroads began to merge. All over the country, the glory days of railroad depots were past; they were becoming vast, run-down, faded behemoths. The Great Northern Depot was no exception.

Youngs quoted one Spokane resident as saying that by 1970 the Great Northern Depot had become a “grim place,” in a “scummy, skuzzy area.” The marble floors had been covered with linoleum, “just like a gigantic bus depot.”

Great Northern had just merged with several other railways to become Burlington Northern and it was unclear whether the new company wanted to keep the depot open at all.

Then came the plans for Expo ‘74, which called for a complete cleanup and renovation of the downtown riverfront. One of the goals was to get rid of the unsightly tangle of railroad tracks that cut off downtown from the river.

With no tracks, there hardly would be any need for a depot.

So the plans called for demolishing both the Great Northern and Union Pacific depots. Havermale Island would be cleared for Expo exhibits and then would become part of the beautiful, green Riverfront Park.

Some historic preservationists were aghast at the idea of flattening these historic buildings. They launched a campaign called “Save Our Stations,” or SOS.

The preservationists might have gotten a little carried away, however, when they composed these words for a historic-places application: “The two depots, when viewed together, form a scene reminiscent of the Piazza del Duomo in Italy.”

Venice it was not.

Most residents were not nearly as enamored of the old depots. One letter-to-the-editor writer parodied the SOS by launching a joke campaign to save the industrial laundry on nearby Canada Island. He called it “Save Our Laundry” or, SOL.

In the end, depot preservation was put on a ballot measure and soundly defeated.

However, as a graceful compromise, the Expo organizers decided to retain the Clocktower as a visible piece of Spokane’s railroad history. And not just railroad history.

Among the many names and initials scratched in the Clocktower’s walls is that of Bing Crosby, who worked as a night watchman for a short time while a student.

So in 1972 and 1973, the wrecking balls slammed into the old depot, although special care had to be taken not to damage the Clocktower. Some people worried that the old tower might fall down when the rest of the depot was ripped away, but that engineering problem was easily solved.

A concrete plinth was installed at the base, and masons bricked up the three sides of the bottom of the tower that previously had been enclosed in the depot.

As Expo approached, the Clocktower was pressed into service as a kind of gigantic digital reminder. Numbers painted on big plywood panels were set up in the upper windows and changed every day.

For instance, with opening day one year away, Spokane residents could look up at the Clocktower and see the number 365.

“If you ever wanted to get heartburn, it’s to see that figure up there and think, ‘Oh, boy, can we get it done? Can we get it done?’ ” said Expo General Manager Mel Alter, as quoted in “The Fair and The Falls.”

The Clocktower, standing alone, turned out to be an even more potent monument than it was before. It became one of the enduring symbols of Expo ‘74.

Artists sketched it. Kodaks snapped it. Families would meet under it.

Today, it is one of the premier symbols of Spokane itself. Yet if it hadn’t been for that grand old depot, it would never have existed at all.

So when the wind blows hard through the top of that old tower, you just might hear a faint moaning sound, just like the sound of a Great Northern train whistle, circa 1902.