Show honors missing man

MOSCOW, Idaho – Since John Dickinson went missing 18 days ago, he’s been missed all over this town.

At the City Council, where he was recently elected president. At the University of Idaho, where he retired from a distinguished career as a computer science professor. Downtown, where he was a frequent presence on his bike and in coffee shops.

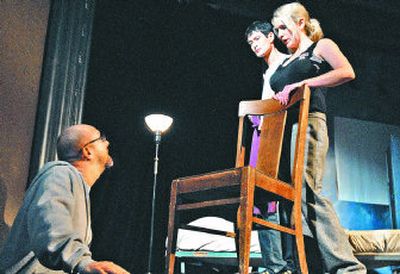

But Dickinson’s absence – since he presumably jumped or fell to his death from a bridge on Oregon’s John Day River on Jan. 7 – may be felt most keenly in the community tonight, when the theater he helped to create opens its latest production, “Touch.” The play was a favorite of Dickinson’s, and it deals with the wrenching loss that friends and family suffer when a woman vanishes.

“I think the opening night is going to be filled with all John’s best friends,” said Teva Palmer, a family friend who lived with Dickinson. “So many people were his best friends.”

Authorities have not found Dickinson’s body, and he is presumed dead. But uncertainty about his fate remains, and some are still holding out hope. The unresolved nature of the case has meant that friends and family haven’t yet had any kind of memorial gathering – no chance to grieve together and talk about Dickinson’s life, his friends say.

Members of Sirius Idaho Theatre, which became one of his passions after he retired from the UI, hope tonight’s performance can provide that opportunity.

“He loved this play,” said Jenny Sheneman, one of the play’s producers. “I don’t know if I could have comfortably produced this play, based on the subject matter, if we didn’t know that this was his favorite play.”

Dickinson’s friends and colleagues describe him as someone who was passionate about political causes, but gentle in argument and kind to a fault. Dickinson took Palmer, a 20-year-old UI student, and a friend into his home two years ago when they were looking for a place to stay, and they’re living there still.

“He wouldn’t let us pay rent,” Palmer said.

He regularly turned over his City Council paycheck to Sirius Idaho Theatre, said Andriette Pieron, one of the board members of the theater company.

“He didn’t even consider it his money,” she said. “He was so incredibly generous in every way – with his heart, with his time, with his money.”

When the news came that Dickinson was missing, people were shocked, though one fact didn’t surprise them: Dickinson and his girlfriend, Julie Bell, had stopped along Interstate 84 to help another motorist, and he is thought to have leapt off the bridge to avoid another car that crashed into his Mini Cooper.

“It was obviously upsetting,” said Jim Alves-Foss, a UI professor hired by Dickinson in 1991. “But the vast majority of us said, “Yeah, John’s the one who would have stopped to help somebody. He’s the guy on the bridge, helping,’ ”

‘Out front’

Dickinson, 62, came to theater and politics late in life, after spending 29 years in the computer science department at the UI as a professor and department chairman. Alves-Foss remembers him as a mentor who helped emphasize what was important to a new professor.

“The job here is about education,” he said. “It’s about reaching out to other people and helping them improve themselves. … It’s about helping people have a better life, and that was kind of the focus when he looked at things.”

Dickinson retired in 2002, after helping to establish his department as one of the top programs in the country for computer security.

Dickinson’s interest in running for office was sparked by the case of one of his students, Saudi Arabian exchange student Sami Omar Al-Hussayen. He was accused of aiding terrorists in a high-profile case that ended with an acquittal on the most serious charges. Dickinson viewed the case as the persecution of an innocent man by overzealous government agents after 9-11.

Dickinson supported Al-Hussayen publicly all through the trial and his subsequent deportation on charges of visa violations.

“When other people were standing back and watching this unfold – including me, I’m sorry to say – John was out front, saying, ‘This is wrong,’ ” said Joan Opyr, a Moscow novelist and writer who worked alongside Dickinson on many liberal causes.

Though Dickinson was motivated to run by his sense of injustice, he was considered a peacemaker and voice of reason on the City Council, friends say. He won election in November 2003 and was selected as council president the week before his disappearance.

Moscow Mayor Nancy Chaney, who ran for office alongside Dickinson, said he was tireless in pursuit of the things he loved, whether it was seeing stop signs put in at a dangerous intersection or supporting the theater.

“He would come to council meetings dressed in character,” Chaney said, describing a night that Dickinson spoke in a Russian accent in the council chambers. “The guy would absolutely not be compartmentalized.”

A second act

Palmer, the friend who lives with Dickinson, said his entry into politics and all the contact with people in the community led him toward the theater. Her mother, Pam Palmer, helped run Dickinson’s campaign, and once he’d won his seat, asked him to help her form a theater.

He agreed, and the two recruited Pieron to be the third board member for the nonprofit Sirius Idaho Theatre, formed in 2004. He also began acting – after having never set foot on a stage before. His first role was as a professor and father of the main character in “Proof.” Later, he played the role of Ben, Willy Loman’s successful brother, in “Death of a Salesman.”

“And he was great in that,” said Noel Barbuto, one of the professional actors who will perform in “Touch.”

The theater is now in its third season. Dickinson also worked hard behind the scenes, on set design, production, publicity – everything. The actors and others involved with Sirius Idaho Theatre said he was more enthusiastic about “Touch” than any play they’d done yet. The play, which has performances running until Feb. 3, is being billed as a “celebration of John Dickinson.”

Parts of it will strike close to home for members of the Moscow audience. The characters in the play struggle with the disappearance of a woman, and the early scenes in particular deal with the pain of that uncertainty.

“The first half of the play is art imitating life imitating art,” said Barbuto. “That’s pretty much what’s happening with John. We can only speculate. Did he jump off the bridge? Did he get knocked off? Nobody knows.”

Much remains unfinished about the circumstances surrounding Dickinson’s disappearance. Without a body or a legal declaration of death, “John is simply not here,” said Chaney. She’ll consider appointing someone to his seat when that changes.

Meanwhile, his family – three children and three grandchildren, as well as a girlfriend he’d recently fallen in love with – and friends are trying to adjust to his absence.

“I miss him terribly,” Chaney said. “There’s no replacing John Dickinson.”