Bush climate change line scrutinized

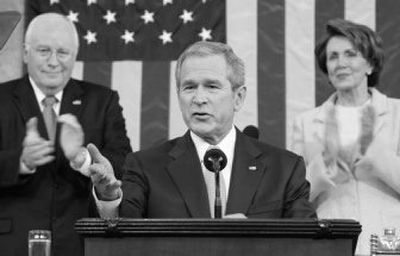

WASHINGTON – It was just a couple of dozen words out of more than 5,000, uttered so fast that many in the audience missed them at first. But President Bush’s commitment to fight global warming in his State of the Union address last week has echoed around the world and provoked debate about whether he is shifting his view of climate change.

The words themselves were not radically different from what he has said in the past in other settings. As he addressed Congress and a national television audience, Bush forecast energy breakthroughs that will reduce U.S. dependence on oil. “These technologies,” he said, “will help us become better stewards of the environment, and they will help us to confront the serious challenge of global climate change.”

But it was the first time in Bush’s six years in office that he mentioned the issue in a State of the Union address. And he did it while presenting a high-profile plan to cut gasoline consumption – and with it, greenhouse gases. “Every word is crafted in that speech and every word has meaning behind it,” said Christine Todd Whitman, Bush’s former Environmental Protection Agency director. “So the fact that he mentioned climate change in that context, that was a step forward, that was a change.”

Leaders in Europe and Asia took notice as well, hailing what they saw as a turning point while renewing pressure on Bush to accompany words with more meaningful action. Environmentalists were skeptical, but said Bush may be starting to respond to the growing political momentum for grappling with climate change.

“They may see some handwriting on the wall,” said David Doniger, climate center policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “They don’t want to look like deniers right now. They’ve got enough problems.” But he said Bush’s proposal could be “a Trojan horse” that looks more important than it really is and, in its details, actually could undermine its own environmental benefits.

Bush’s plan calls for reducing projected gasoline consumption in the United States by 20 percent over the next 10 years by mandating a dramatic expansion in the use of alternative fuels such as ethanol and raising fuel efficiency standards for automobiles. According to the White House, that would cut annual emissions from cars and light trucks by 10 percent, or 175 million metric tons, equal to taking 26 million cars off the road.

While welcoming the initiative, environmentalists noted the 20 percent goal applies to how much gas is forecast to be used in 2017, not how much is used now. Because of an expected increase in consumption over the next decade, such a cut would not reduce the amount of gas currently consumed. Moreover, they complain that alternative fuels encouraged by the administration include liquid made from coal, which emits its own toxic gases.

The Bush plan fell far short of the mandatory reductions in greenhouse gas emissions envisioned by the 1997 Kyoto accord, which Bush renounced in 2001. Days before the State of the Union speech, there was speculation he might embrace emission caps after James Connaughton, head of the Council on Environmental Quality, said he agreed with such an idea “in concept.” But White House spokesman Tony Snow slapped down the idea and the speech made no mention of it.

“To be perfectly frank, I thought it was an appalling disappointment for everyone, whether you’re on the right or the left,” said Samuel Thernstrom, a former Bush environmental aide now at the American Enterprise Institute. “We had all been led to expect … that we would hear a very substantial initiative from the president.” Instead, he said, Bush’s plan is “essentially trivial, it’s marginal.”

Global warming has long been a political sore spot for Bush. During the 2000 campaign, he seemed to doubt that it was a major problem or that human activity contributed to it. “There’s differing opinions,” he said. “And before we react, I think it’s best to have … full understanding of what’s taking place.”

After taking office, he withdrew the United States from Kyoto and, amid energy shortages in California, broke a campaign promise to impose mandatory reductions in power plant carbon dioxide emissions. The Kyoto move did not represent a major policy shift because the Senate had already made clear it would not ratify the pact because of possible economic consequences. But the administration had not prepared allies, and the move became an enduring symbol of Bush defying the world.

In 2002, Bush unveiled a plan to reduce the intensity of greenhouse gases 18 percent by 2012, but environmentalists dismissed his ideas as inadequate. In 2005, however, Europeans sensed a shift when Bush was asked about the issue in Denmark. “Listen,” he said, “I recognize that the surface of the Earth is warmer and that an increase in greenhouse gases caused by humans is contributing to the problem.”

Climate change began inching up the Bush priority list because of energy security. With oil prices spiking, disruptions to domestic production by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 convinced Bush that more needed to be done to diversify U.S. supplies, aides said. He declared in last year’s State of the Union speech that “America is addicted to oil.” And he chose as treasury secretary Goldman Sachs Chairman Henry M. Paulson Jr., an advocate for aggressive action on global warming.

Meanwhile, states led by California launched their own efforts to rein in greenhouse gases. Corporate executives began agitating for a consistent national policy.

As the White House began developing a new energy policy in the fall, Paulson pushed for bold action. Instead of a laundry list of small-bore initiatives, Paulson said they should set an ambitious goal, then determine how to get there, officials said, leading to the idea of a major cut in gasoline consumption. By November, prodded by Paulson and Energy Secretary Samuel W. Bodman, officials decided to make curbing greenhouse gases another goal of the policy.

“Since Secretary Bodman was committed to doing something about the climate change issue, he saw (fuel efficiency) as a win-win. It reduces our dependence on foreign oil, the vulnerability of the economy to oil price shocks and helps cut our greenhouse gas emissions,” said David W. Conover, former head of the department’s climate change technology program.

Outside the administration, another person who may have helped shape the president’s thinking was FedEx Chairman Frederick Smith, a Bush fund-raiser and friend whose business is sensitive to energy costs. During a campaign swing through Memphis last year, Bush attended a private dinner that included Smith. The conversation dwelt on national security but also touched on energy, Smith said later. Smith chaired the Energy Security Leadership Council with former Marine commandant P.X. Kelley and through the fall made the case that a disruption in global supplies could be devastating.

“The dependence of the United States on foreign imported petroleum, after nuclear proliferation, is the country’s largest economic and national security issue,” Smith said in an interview. “And if the country doesn’t do something to reduce the amount of imported petroleum we’re going to have a very unpleasant economic correction or national security challenge.”

Smith, Kelley and Goldman Sachs vice chairman Robert Hormats met Dec. 13 with White House economists Al Hubbard and Ed Lazear to present ideas, many resembling those built into the State of the Union address. “They were very receptive,” said Hormats. “You can tell the difference between a meeting where they’re going through the motions and where they’re genuinely searching for new ideas. They weren’t in defensive mode. They recognized that more needed to be done.”

Bush still opposes Kyoto and argues that greater technology will solve the problem. The White House said he has devoted $29 billion to climate science, aid and incentives and last week he ordered government agencies to buy more hybrid-fuel cars. “We can get beyond … the pre-Kyoto era with a post-Kyoto strategy, the center of which is new technologies,” he said on a visit to a DuPont facility in Delaware the day after the State of the Union address.

Former EPA chief Whitman said that for the first time Bush may be willing to sign carbon emission caps into law. “He’s kind of setting up for a carbon-constrained economy,” she said. “I don’t know whether there will ever be an administration bill, but it may be that he’s setting himself up not to veto (someone else’s) bill.”