Island solitude

With one last sweep of the paddle, gravel crunches under my hull as I beach my kayak and pop my spray skirt. I sit for a minute, watching the waves gently lap at the pebbly shoreline and admiring the dense canopy of deep-green forest stretching from beach to ridgetop.

Overhead, a lone bald eagle soars, silently. Gone are the noisy rafts of pleasure boats and traffic-choked ferry docks I’m so used to seeing on my trips to these San Juan Islands. Here, I can contemplate what things used to be like before wave of new vacation homes and the crush of tourists – lush, serene and lonely.

A buddy and I have made the trip to Cypress Island for a weekend of unwinding and exploring. Like many, I’d spent my share of time on trips to the San Juans waiting for hours in frustrating lines and elbowing my way through crowded campsites. This time, I wanted something different. And, as I scanned the beach and realized that there wasn’t another human being in sight, I realized that I’d found it.

Cypress Island is a true anomaly in the San Juans, historically spared by development due to the Island’s difficult access, rugged terrain and poor farming soils. While it’s geographically close to the mainland and the far more visited islands served by state ferries — San Juan, Orcas and Lopez and Shaw — Cypress Island feels like a world of its own. A tiny population of about 40 residents cluster along its southern tip, leaving about 90 percent of the Island’s 5,500 acres as public land managed by the state’s Department of Natural Resources as a conservation and natural area.

With no commercial ferry service or amenities attract crowds of tourists, Cypress remains the domain of nature, and a fitting destination for outdoor exploration.

While Cypress Island has long been coveted by kayakers and boaters for its lively offshore currents and scenic shoreline campsites, hikers have often overlooked the Island’s miles of trails, which wander through lowland forests, along quiet sand and cobble beaches and over grassy balds. Particularly in the off-season months in early spring, fall and winter when cooler weather and rougher waters discourage boaters, you’re likely to find trails and even campsites to yourself.

“Winter can be a very enjoyable time when you’ll encounter few people, if you don’t mind a bit of rain,” says Krist Thomsen, Department of Natural Resources public use and natural resources manager.

About 20 miles of trails cover the Island, many of them following remnant logging roads, where we find twisted cables and decaying log piles that tell tales of the old timber days. Today, forests of Douglas fir, western red cedar and western hemlock blanket much of the island, along with grand fir, western hemlock, shore pine, Sitka spruce and Pacific yew. Pacific madrone and Rocky Mountain juniper grow on drier slopes, along with Idaho fescue, camas and colorful paintbrush, creating plant communities rarely found in western Washington.

After a full day of wandering, we realize that it’s not possible to explore the whole Island in one day. Besides, a quiet night camped along the beach, soothed to sleep by salt air and lapping waves is one of the best rewards.

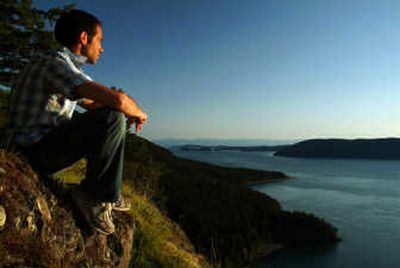

From our camp at Pelican Beach on the northeast side of the Island, my buddy and I set off on the 2.6 mile out-and-back hike to catch the sunset from Eagle Cliff, the Island’s most spectacular vantage point.

Climbing from the beach through lush Douglas fir and western red cedar forest, the trail breaks into open country after about a mile. We scramble over rocky ledges to the cliff, where we find jaw-dropping views down to Rosario Strait below, across Obstruction Pass and Orcas Island and south to the Olympic Peninsula. Staying on the trail here helps to protect sensitive plants and the fragile soils. The trail is also closed seasonally from February 1 to July 15 to protect peregrine falcons that nest in the cliff.

The next morning, we explore another moderate 2.8 mile loop that wanders past Duck Lake, a spectacular wetland for bird watchers, and on to Eagle Cove at the head of placid Eagle Harbor. Resting on the sheltered pebble and sand beach, we enjoy the chatter of kingfishers swooping over the water, and watch herons gracefully forage along the shoreline.

“The more than 120 species of shore, wetland and forest resident and migratory birds observed on and around Cypress are perhaps the Island’s largest draw for wildlife lovers,” notes Thomsen.

From Duck Lake, we hike the 2.4 miles out and back to Smuggler’s Cove on the east side of the Island, where we find more sweeping views over Rosario Strait.

South of Eagle Harbor, the 4-mile long Cypress Mainline Road, another remnant logging road, accesses trails on the south side of the Island. Along the way, a short 0.5-mile spur trail leads to Cypress Lake, the largest lake on the Island. At the south end of the Mainline Trail, the Reef Point and Strawberry Bay Trails take us to the west side of the Island. Please respect private property signs here and stay on the trail.

We discover more spectacular waterside camps at Cypress Head, connected by a tiny spit to the east side of the Island. A surprisingly grueling 2.1-mile climb from here up the Cypress Head Trail provides access to tiny Reed Lake. Another 2.2 miles of trail wind their way to the Island’s small airfield for still more outstanding views to the north and southeast and on to Bradberry Lake, another one of the Island’s many small ponds and lakes.

The next morning, with tired legs and a sense of renewal, we load our gear and pull away from the shoreline of Cypress, leaving behind the beach and forest—alone again.

(Dave Wortman is author of the Falcon Guide series book “The San Juan Islands: Exploring the Great Outdoors.”)