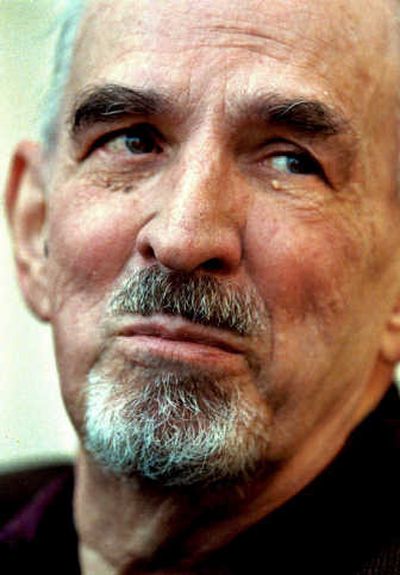

Bergman created stark masterpieces

Ingmar Bergman, an Academy Award-winning Swedish writer-director whose name came to define an entire genre of stark movies about the human condition, such as “The Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries” and “Persona,” died Sunday at his home on Faro Island, Sweden. No cause of death was disclosed for Bergman, who was 89.

The “Bergmanesque” style of intensely personal cinema, in which desire and suffering dominated the character’s lives, first gained wide attention in the early 1950s – when many American filmmakers were making soapy dramas or promoting gimmicks like Smell-o-Vision.

In Europe, movie directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut helped break visual and narrative rules, but Bergman stood out for dreamy and often disturbingly psychological films that expressed emotional isolation and modern spiritual crisis.

Women were especially prominent in Bergman’s films and not as cardboard heroines. Confused by their doubts and desires, sometimes entirely driven by their passions, Bergman’s female characters usually stood on the brink of mental collapse. Meanwhile, his men were often hapless bystanders, incapable of understanding their own lives, much less those of anyone around them.

“The people in my films are exactly like myself – creatures of instinct, of rather poor intellectual capacity, who at best only think while they’re talking,” Bergman once said. “Mostly they’re body, with a little hollow for the soul.”

To Bergman, solace was only possible through erotic and intellectual connections. But he believed people isolate themselves by cloaking their emotions.

Film critic and scholar David Sterritt said Bergman made it fashionable among American audiences to discuss movies as an art form. “He showed that cinema could be a genuine art that could take on the deepest of all human themes.”

Three of Bergman’s movies received Oscars for best foreign language film: “The Virgin Spring” (1960), about a 14th-century Swede who avenges the rape and death of his daughter; “Through a Glass Darkly” (1961), about a crumbling modern family; and his final film, “Fanny and Alexander” (1982), a story of an adolescence that is often terrifying.

Bergman worked closely with his cameramen to create some of the most memorable images in 20th-century cinema. One such moment was the finale of “The Seventh Seal” (1957), in which a parade of characters dance to their doom with scythe-wielding Death leading the way.

Between films, he retreated to his home on the rainswept, stony seascape on Faro Island in the Baltic Sea, and spoke of his need to live remote from civilization, among the sound of waves and a ticking grandfather clock.

He called the island an ideal place for him to confront his daily fears about death. “The demons don’t like fresh air,” he said in a Swedish documentary last year, “Bergman Island.” “What they like best is if you stay in bed with cold feet.”

His marriages to Else Fisher, Ellen Lundstrom, Gun Hagberg and pianist Kabi Laretei ended in divorce. His fifth wife, a countess named Ingrid Karlebo von Rosen, died in 1995.

He reportedly had nine children among his wives and other relationships.

On his admitted disregard for parenting, he told the documentarians in “Bergman Island”: “I had a bad conscience until I discovered that having a bad conscience about something so gravely serious as leaving your children is an affectation, a way of achieving a little suffering that can’t for a moment be equal to the suffering you’ve caused. I haven’t put an ounce of effort into my families. I never have.”