Silver standards

As much as any player has, Dave Staton owned the Northwest League.

This was 1989, and nobody stung the baseball harder, more often or in a timelier fashion. At 6-foot-5 and 215 pounds, just his stroll from the on-deck circle intimidated opposing pitchers. He won the league’s Triple Crown – batting average (.362), home runs (17) and runs batted in (72) – in leading the Spokane Indians to another pennant, a four-bagger never pulled off before or since.

Naturally, such a monopoly led him to assume he’d pass directly to Go, or at least to Double-A ball the next year. But instead, Staton’s bosses, the San Diego Padres, inched him up only as far as Class A Bakersfield – where he opened the season hitless in his first 25 at bats, with 16 strikeouts.

“I wanted to prove to everyone else that I didn’t belong in the Cal League,” he laughed, “and it was like the Cal League got together and said, ‘Yeah, you do.’ “

They say the biggest jump in baseball is from Triple-A to the big leagues, but the more daunting climb starts at the base camp of baseball – the short-season leagues.

On Tuesday night, the Indians open their 25th season since Triple-A baseball left town for good, though their short-season history in the Northwest League also includes the summer of 1972, as a Dodgers farm club. So it’s both 25 seasons and a 25th anniversary of a marked changeover at the old Fairgrounds ballyard.

What was mostly just baseball in the Triple-A days now leans to entertainment – and player development.

So now’s as good a time as any to see how things have developed.

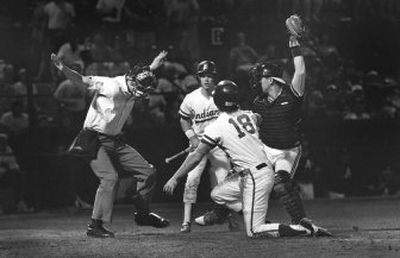

Yes, there have been some rockin’-good baseball times in the short-season years – Staton’s Triple Crown, seven championships (including four in a row starting in 1987), Glenn Dishman’s no-hit and near-perfect game of 1993 and, best of all, the steal of home by Mike Humphreys that won the 1988 pennant. There have also been comical lows: the 2001 Indians finishing an impossible 30 1/2 games out of first, general manager Les Yamamoto’s ill-considered decision to sell 50-cent beer on Opening Night 1985 – and a worse one in 2002 by manager Tom Poquette, when he pulled Greg Atencio three outs away from completing a no-hitter, in the next-to-last game of a lost-cause season.

That, as much as anything, drove home the point that the major league parent clubs – the Padres (1983-1994), Royals (1995-2002) and Rangers in succession – have but one concern: getting their players from here to there.

It’s their dime, of course, but here’s the thing: The numbers never really change, no matter what the approach.

In the short-season years, 86 Spokane players have made it to the major leagues, not counting any originally sent down on rehab assignments. That’s about 11 percent. Throw out the last two seasons on the theory that there hasn’t been enough time for any of those Indians to make themselves ready, and that averages out to 3.7 players from each Spokane team.

Which is pretty close to what it was 35 years ago, when Indians owner Bobby Brett played his first season of pro ball in Billings, Mont.

“And sometimes you never know who’s going to make it,” he said. “There are guys you think are obvious and something happens to them, and then there are the guys you can’t believe.

“Kiki Calero’s pitching with the A’s and you look back at him here and think, ‘How the hell did he make it?’ Matt Mieske was a very good player, but you thought he was probably as good right here as he’d ever be. Mark Ellis – you could hit him ground balls all day and think, yeah, he’s a good player, but not off the charts.”

Of course, that’s a day-to-day occurrence in baseball – that you-can-never-tell-feeling.

Dishman, now a pitching coach for the Great Lakes Loons, the Dodgers’ Midwest League team, recalled that all too well of the day in Yakima when he threw his no-hitter – a perfect game until first baseman Jason Thompson booted the 27th out.

“I was warming up in the bullpen that day and I was walking back to the dugout with the relievers,” he said, “and I told them, ‘You’d better be ready today, because that was ugly.’ I couldn’t throw a strike in the bullpen to save my life.”

Dishman himself bears out that delicate uncertainty of a baseball career. A dominant pitcher here and at other minor league stops, he made it to the majors but pitched in just 33 games. Staton’s career flamed out after two abbreviated stints with the Padres. Juan LeBron, thought by some to be the athletic equal of outfield mate Carlos Beltran in Spokane, never cracked The Show at all.

And yet Brian Shackelford, who played here as an outfielder in 1999, wound up making it as a pitcher with Cincinnati in 2005.

But every Indians season has produced at least one intriguing prospect – including that 1972 interregnum between the Dodgers taking their Triple-A team to Albuquerque and Texas supplying a replacement. A good pitcher – Don Standley, who threw nine complete games in the era before pitch counts – didn’t make it to the big leagues off that team. But a terrific athlete named Glenn Burke did – though he’s remembered more for pioneering the high five and being baseball’s first openly gay player.

If the 24 seasons since haven’t produced a Hall of Fame team, they were peppered by players who went on to make 13 All-Star Game appearances, win one Rookie of the Year award and contribute one legendary nickname – “Wild Thing” – to both baseball and Hollywood.

That would be Mitch Williams, the eccentric reliever who became the first post-1982 Indian to make the big leagues, with Texas in 1986. The latest is Rangers infielder Travis Metcalf, who played here as recently as 2004.

So what do they learn here? Mostly how to survive.

“That was my first full season and what got to me was the grind,” said Dee Brown, a Royals No. 1 pick and the league MVP in 1997. “You’re playing every day and traveling on game days, and the second full month of the season was like night and day from the first. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but you learn that it is and that you have to prepare yourself for it.”

Organizations learn how willing their more talented players are to embrace that concept, or if less gifted prospects can enhance their stature through sheer work. Sometimes the short-season player is too naïve to be nonchalant.

“I see a different attitude at this level than what we had,” said Dishman. “It’s that work ethic. Here, you have to push them more. We were scared not to work hard. With Charlie Greene, my pitching coach in Spokane, if I didn’t do double what he said I felt like I wasn’t doing enough.”

And that’s as crucial as anything – helping yourself.

“Every organization is looking for major leaguers and the I’m-getting-screwed guys just hurt themselves,” said Brett. “Yeah, maybe a higher draft pick is going to get an extra look because a team has more invested, but guys who are undrafted make it, too. But those are guys who love the lifestyle, who grind and fight. I think of Dave Hollins, the old third baseman here, who used to yell at the other dugout and really fought for his teammates.

“I heard Scott Boras, the agent, speak at a camp at Arizona State for high school juniors. He said that in the major leagues, there’s about 7 percent of the players who just have exceptional talent – the A-Rods and Jeters, the superstars. The other 93 percent are just good players who found their way through the system, who found a way to survive, who can grind it out and battle. They did something well enough and long enough that it got them a chance.”

Which, in the end, is all any of the Indians of 2007 can ask for – a chance to be one of the 3.7 who will make it to the big leagues.