Immigration scrutiny puts Chattaroy man’s life on hold

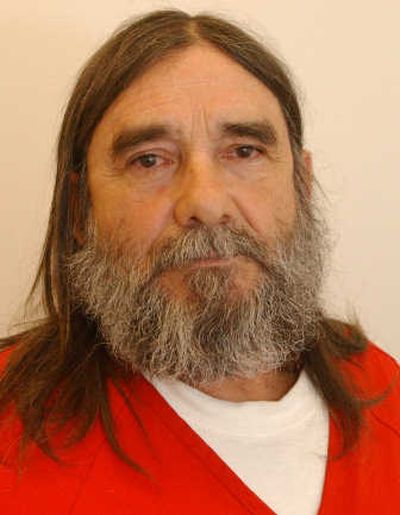

TACOMA – Johnny Malito spends his days among the white walls and steel doors of a federal immigration detention center here, awaiting a letter he hopes never comes.

Convicted on drug and gun charges nearly two decades ago, Malito was allowed to remain in the United States. But convicted of two more counts of the same gun charge last year – and having already served his sentence in state prison – the Chattaroy gardener is being held indefinitely. The government is trying to deport Italian-born Malito to the country he left as a boy more than half a century ago.

Foreign criminals living illegally or legally in the United States are a growing priority for federal immigration officials, who are expanding efforts to remove them. Since 2005, for example, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has quadrupled the number of federal prisons where it looks for criminal aliens.

“Like everyone else, we have our priorities, and criminals are our No. 1 priority,” said Bryan Wilcox, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s deputy field office director for detention and removal in Seattle.

Malito’s case “is unusual in the sense that the guy’s been here such a long time, but it’s not unusual in the increased sense of scrutiny for cases like these,” said Pedro Rios, a San Diego immigration expert who works for American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization.

If Italian officials authorize his return, Malito, at 60, will be trying to start over in a country and language he barely remembers.

Malito’s situation, federal officials say, is entirely of his own making.

Eighteen years ago, Malito was convicted in California of possession of marijuana with intent to sell. Two years after that, he says, an Oregon hunting trip led to him being convicted of being a felon in possession of a firearm.

Either of those crimes would have been enough to deport Malito, said Greg Fehlings, deputy chief counsel at the Seattle office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Instead, the Illinois-raised Malito settled in 1994 on 20 acres near Chattaroy. Living on disability payments from a head injury decades ago, the former welder raised pigs, grew a large garden, tended fruit trees and built a home with his American-born wife, Jeanne. They sold vegetables from a roadside stand and gave away hundreds of ears of corn each summer.

Malito also grew marijuana, which he said helped with the sleeplessness from the old injury. He has a medical-marijuana prescription, a copy of which his wife provided to the newspaper.

Neighbors and acquaintances describe him as often erratic – telling people that he’s Jesus Christ, or claiming that he’s a “deep undercover” FBI agent – but not dangerous.

“He was harmless as hell,” said David Carr, a retired construction worker who lives nearby. “Johnny’s not a bad sort.”

Then, one September morning two years ago, Malito went to Frank’s Diner on the Newport Highway. He was a regular there, coming in almost daily to sit at the counter and talk to a couple of waitresses and the cook.

He was wearing a blue-and-red striped robe over his clothes. But on his hip under the robe was a holster holding a loaded Smith & Wesson .50-caliber revolver. An alarmed customer quietly summoned police.

Deputies arrived and found another loaded gun in Malito’s car trunk: a 7.62 mm SKS rifle, along with two swords, a hatchet and several knives. He was arrested.

“He was never really a threat, just kind of a goofy character,” said a waitress named Patty, who wouldn’t give her last name. He would regularly show up for coffee in his “Job-like robe,” she said, to talk about politics and the Bible.

“I feel like the poor guy was probably just off his medication. He was a very strange person. Very nice, though.”

Malito says the guns, owned by his wife, were for shooting coyotes preying on his piglets and other livestock.

He pleaded guilty to two counts of unlawful possession of a firearm. He served just over a year in prison, most of it at Airway Heights. On the day he was released, he said, an Immigration van arrived that brought him to the sprawling federal detention center on Tacoma’s industrial tideflats.

“That was the worst trip of my whole life,” Malito said.

The couple sold half their land – 10 acres – to pay for an immigration attorney who they say assured them he could get Malito released on bond. Jeanne Malito traveled to Tacoma so she could be in the courtroom, to show the judge that her husband had a supportive family.

The judge, who appeared over a video link, denied the bond.

Since March, Malito’s home has been the federal Northwest Detention Center.

Owned and operated by a private firm called The Geo Group, the 1,000-detainee facility is one of 16 such centers used by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

It’s a brightly lit labyrinth of steel doors, cameras and thick glass tucked among the rail sidings and trucking yards near the port. The recreation yard and bus parking lot are ringed with razor wire.

“DETENTION IS NOT PRISON,” reads part of a 25-page pamphlet issued to newcomers. “… Try not to take things personally. … You are stronger than you think and you can cope. … The fact that you are in detention does not mean you MUST feel anxious, worried or depressed.”

The pamphlet outlines the rules: Walk, don’t run. Address staffers by rank and last name. Beds must be made by 8 a.m.

There are two courtrooms, a medical and dental clinic, a kitchen. Detainees who work are paid $1 a day. They can buy snacks, toiletries, phone cards.

The detainees are from a wide array of countries. Those in the center’s one-room law library on a recent afternoon, for example, were from Nigeria, Trinidad, Vietnam, the former Yugoslavia, Peru and El Salvador. Their stays at the facility, they said, ranged from 10 days to three years.

Those who agree to be deported typically leave quickly, unless their home country won’t take them. Some former Soviet republics and Southeast Asian countries are very reluctant to take their citizens back, said Wilcox, with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In those cases, the detainee is held as long as there’s reasonable hope of repatriation in the near future. Otherwise, the detainee is released and told to report periodically to a local ICE officer.

“We can’t send them to a country that won’t accept them,” Wilcox said.

That – being a man without a country – is Malito’s last hope. Desperate to get out of the Tacoma center, he says, he reluctantly signed papers agreeing to be deported. But he and his wife are hoping that Italian officials will decide not to accept him.

“I’m not really an Italian. I’m an American,” he said. He says he thought – erroneously – that he became a citizen when he was drafted into the U.S. Army decades ago.

So he waits for the mail to decide his fate. He sketches, he reads and he burns through $40 worth of phone cards a week, mostly talking to his wife on a pay phone. He longs for fruit and the sight of trees and green grass. He complains about the detention center food and health care, calling it a hellhole. (Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials say that the 2,900-calorie daily diet is dietician-approved and that anyone can see health workers at morning sick call.)

Malito says he worries about being forced to leave behind his 80-year-old father – now a U.S. citizen – and 10 grandchildren.

“What Christmas am I going to have without my grandkids?” Malito said, sobbing during an interview in a detention center visiting room.

Some of his neighbors are upset with what’s happened.

“He got a raw deal,” Carr said. “It’s pitiful, when you have a person that doesn’t do nothing but grow food and help people. … It’s a farce what they’re doing to him.”

“I think it’s crazy,” said Ira Brock, a retired Spokane parks and recreation worker who lives nearby. “We know John, and we know he’s harmless.”

No matter what happens, it seems, Malito will lose his home and land. In 2005, a drug task force raided his marijuana crop and – although, the Malitos say, all charges were dropped – is seizing half the property. (Federal law does not recognize any medical use of marijuana.) Gone are the pigs, the cows and the goats. Jeanne Malito said she’s been given six months to sell their remaining 10 acres, with its three-bedroom home, chicken coop, fruit trees and view of Mount Spokane.

“I’ve got stuff packed because I don’t know what’s going to happen,” said Jeanne Malito.

Her husband has suggested that she divorce him if he’s deported, to spare her the prospect of trying to build a new life in an unknown country at age 61. But she said she’ll go, too.

“I want to be with him,” she said. “If I don’t have my husband, I don’t have anything.”