Vitale appreciates life and gives back

BRADENTON, Fla. – It’s lunch time on a Wednesday and Dick Vitale is sitting at a round, wrought-iron table outside The Broken Egg restaurant, the pile of newspapers around him gently rustling in the soft, warm Florida breeze.

After 28 years of chasing college basketball games around the country for ESPN, the games – specifically the ACC tournament – have come to Vitale, who lives 50 miles south of Tampa in the sunshine of his life.

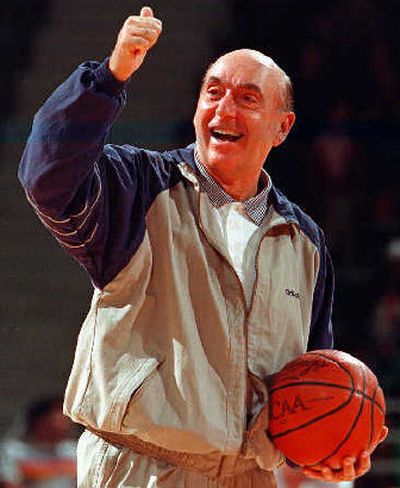

A bowl of chicken vegetable soup arrives, and Vitale needs 15 minutes to get through it because, if it isn’t Bobby Knight calling on his cell phone, it’s a guy from Elmira, N.Y., stopping by the table to ask the balding, 67-year-old unlikely celebrity to suggest two bracket-busters for his NCAA tournament bracket next week. “Winthrop and Davidson,” Vitale says, pulling out a Sharpie to scrawl his signature – as oversized as his personality – on a copy of one of his seven books.

When he’s home, the man who taught sixth grade in East Rutherford, N.J., while dreaming of being a college basketball coach loves to spend his late mornings at the restaurant, perusing the day’s papers, taking and making calls while constantly interrupting himself to say hello or wave to restaurant guests who recognize him.

More than three hours before his soup arrived, Vitale played two sets of tennis with a friend.

When time permits, Vitale drives a few miles over to Siesta Key and walks on the white-sand beach to clear his mind, plan his day and remind himself of how amazingly fortunate he has been. “My life has exceeded my dreams,” he said.

He has two daughters, five grandchildren and more money than he ever imagined. His mother sewed coats in the family basement and his father pressed coats, scratching together enough money to keep a family going, and now their son lives in a gorgeous home on a golf course underneath what seem to be perpetually blue skies.

For years, Vitale kept a folder of rejection letters he got from colleges such as Lafayette and Bucknell that always wrote back, “Dear Richard” and broke his heart again. His buddies thought he was crazy to think he could coach in the big time, but Vitale’s mother put her arm around her son one day and told him, “You’re going to make it because you have spirit.”

That’s like saying Walt Disney had imagination.

In 1978, Vitale’s coaching career ended suddenly when he was fired by the NBA’s Detroit Pistons. A few months later, an upstart network named ESPN persuaded him to try announcing and, after initially saying no, Vitale’s new life was born.

Sure, he’s like a Disney character in some ways, his words and actions exaggerated for effect. He admits to being protective of coaches because he was a coach. That’s why, when the games end, he always watches the losing coach leave the court, remembering how it felt.

For a man who’s become community property in the college basketball world, there is a side of Vitale the public doesn’t often see. Between bites of a turkey burger named for him on the lunch menu, Vitale nearly chokes up talking about a 9-year-old girl fighting cancer and an acquaintance whose daughter recently died.

Vitale has given time, money and prayers to them and so many others.

He has organized and hosted dinners and fundraisers, championing the V Foundation in memory of his late friend, Jim Valvano.

People close to Vitale can tell you how he surprised a man who does odd jobs around his house with a $65,000 car because he wanted to do something nice for a good man.

Vitale doesn’t ask to be thanked for those things. It’s his way of saying thanks for what he has.